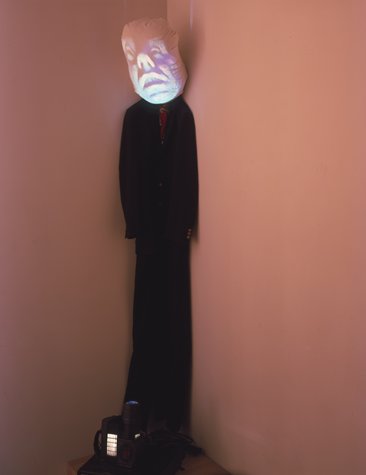

Tony Oursler, "F/X Plotter #2," 1992. Cloth and video projection, dimensions variable. Courtesy SFMoMA.

The video artist Tony Oursler is perhaps best known for his video projections of human faces onto the heads of small doll-like bodies. Lying on the ground or hanging limply from a pole in the corner of a gallery space and speaking in anxious, angry or even hysterical tones, these disturbing little effigies with their lifelike faces often startled passersby. Oursler’s practice of projecting human heads onto otherwise deflated bodies has been associated with the Freudian uncanny, since the confusion between the living and the inanimate is one of the uncanny’s key features. In Peak, Lehmann Maupin’s current exhibition of new work by Oursler, the artist continues to elaborate his professed interest in the uncanny, now exploring the ways in which virtual systems and spaces are increasingly becoming proxies for our psyches and consciousness. As the press release states, “Oursler [investigates] our contemporary Internet usage, viewing the Internet as a mechanical reflection of our human psyche, inducing a compulsive relationship despite its disturbing effect. The dynamic developing between humans and the virtual apparatus becomes and is an epistemological mirror of the human consciousness and, thus, is uncanny in its nature.”

It is certainly fair to say that Oursler’s works in Peak are about the uncanny, but when standing before these new objects, one no longer senses that they aim to induce in us an experience of the uncanny on the order of his earlier, seemingly preternatural dolls. Collectively, the works in Peak seem instead to intimate that the uncanny is no longer something we encounter outside ourselves, stumbling upon it in the world around us, but is now a constitutive feature of ourselves already internalized in our twenty-first century lives. In these new works, the loss of our autonomous selves in and through new technologies appears not as an impending threat but as a structuring principle of our very being.

The concept of the uncanny—famously elaborated in a 1919 essay by Sigmund Freud—can be in part understood as that peculiar sensation induced by something which renders our familiar and seemingly coherent perception of reality and our place in it suddenly uncertain. One of Freud’s classic instances of such an unsettling disturbance in our world is the figure of the doppelgänger. To encounter one’s own double, even if only in the form of a momentarily unrecognized reflection in a mirror or store window, is to experience a moment that unsettles our normal conception of reality and threatens our sense of ourselves as unique in the world. What ultimately places the doppelgänger within the dimension of the uncanny is that it both is and is not us, a foreign yet familiar figure that provokes in us a sense of radical difference and estrangement at a moment that should otherwise be an occasion of most intimate resemblance.

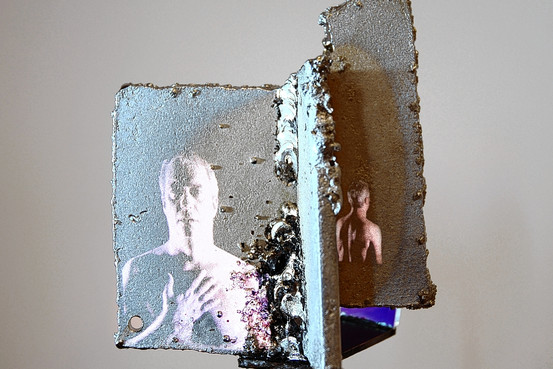

Tony Oursler, "Mirror Return" (detail), 2010. Projector and video projection, chromed steel, and dichronic plexi mounted on steel armature. Image courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery.

If his earlier dolls performed the role of the doppelgänger in momentarily disturbing or shocking us upon our encounter with them, then in Oursler’s most recent work, the uncanny’s challenge to our sense of autonomy has now become internalized—an already given feature of (self) identity. In Mirror Return (2010), for example, we are presented with a tiny video projection cast onto a small slab of chromed steel. The short video loop consists of a man (Oursler himself) repeatedly looking over his shoulder while saying to no one in particular such things as, “That’s so strange. It’s just me…it has to be, but it’s not me,” and “from you to me, from here to there. Irreducible to anyone, to any one signifier.” Complementing the audio’s implication of a psychologically fragmented subjectivity is the divided presentation of the video itself (a portion of the video projection can be viewed here). Presented twice and from two different camera angles, the protagonist of Mirror Return is shown in one projection close up and from straight on while a second, smaller projection off to the side presents the same figure from behind and from farther away—a synchronized double image at once familiar yet strange. For the protagonist of Mirror Return, the uncanny sense of radical self-estrangement is not prompted by some external catalyst, but is an internal state of being (“That’s so strange,” he says, “It’s just me.”).

This inward turn seems to pervade many of the works in Peak. In part, this sense is created by the scale of Oursler’s video projections, which are now often no more than a few centimeters in height. Unlike with Oursler’s earlier video projections, one now has to lean in quite close to see the figures and hear the audio of each work. As a result, Mirror Return and the other works fail individually and collectively to charge the exhibition space with the same psychological intensity of their ragdoll predecessors. This isn’t to say that Oursler’s new work isn’t effective, but that the change in the conditions of our viewing experience suggests to me a change in our relation to the uncanny. No longer disruptive, Oursler’s latest projections pull us closer to them, drawing us in to look and listen. His projections have become intricate, diminutive, and calm. In several of the sculptures, the projected figures, far from engaging or confronting us, merely wriggle and writhe across the sculptural surfaces, seemingly on some silent, Sisyphean quest.

The exhibition’s title, Peak, alludes to the roboticist Masahiro Mori’s “The Uncanny Valley,” which reconceptualizes Freud’s uncanny and theorizes that as the gap slowly closes over time between the appearance of inanimate objects and our animate selves, the objects that were once pleasing will cross a certain threshold of resemblance to us, becoming uncanny and repulsing us. But it seems to me that a work like Mirror Return raises the prospect that such a threshold is by no means clearly demarcated, and may in fact have already long since been crossed. In Mirror Return, the projected figure is one already deeply penetrated and fragmented by the alienating effects of technology—an internalized state echoed in its external forms. This and the other projected figures in Peak—especially those writhing across the surfaces of the various sculptures—cannot be said to be resistant bodies poised to repulse and reject uncanny objects when they appear. No longer shocking or even disrupting, Oursler’s figures are little more than traumatized, unresisting beings groping about figuratively and often literally for some lost object that, in the case of the uncanny, is perhaps their own lost sense of self.

Peak, an exhibition of new works by Tony Oursler, is on view at Lehmann Maupin in New York through December 5, 2010.