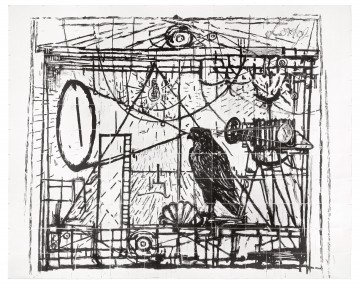

William Kentridge, "Learning the Flute," 2004. Letterpress on 110 sheets of Arches Johannot, edition of 18 (another 18 impressions were printed on disbound pages of Chambers’ Encyclopaedia, 1950, of the same size). Assembled overall: 9’ 3” x 11’ 7 ½” (281.5 x 354.6 cm). Published by Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

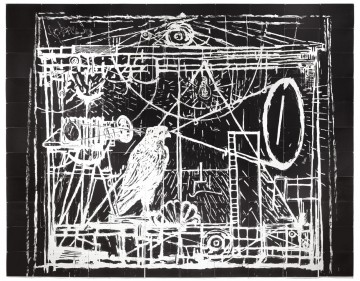

William Kentridge, "Learning the Flute" (reverse), 2004. Photolithograph on 110 sheets of Arches Johannot, edition of 18 (another 18 were printed on disbound pages of Chambers’ Encyclopaedia, 1950, of the same size). Assembled overall: 9’ 3” x 11’ 7 ½” (281.5 x 354.6 cm). Published by Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

The recent release of William Kentridge: Anything is Possible invites exploration of the artist’s significant body of prints, which currently numbers over 400. A natural match for his artistic philosophy and political subject matter, printmaking has always been a significant means of expression for Kentridge. His virtuosity in printmaking is apparent in the impressive variety of approaches he has employed, each of which contributes to an extremely rich body of work that invites dedicated attention.

As demonstrated in the recent exhibition and catalogue William Kentridge: Five Themes,1 much of Kentridge’s work has been guided by motifs that he explores in a variety of formats, from theater to drawing to animated film and, of course, printmaking. Myth, political history, literature, the performing arts, and cultural artifacts are a few of sources that inspire Kentridge’s investigations into the nature of being human and “the persistence and robustness of contradiction.” 2

Kentridge’s working process requires space for uncertainty and exploration, a fertile condition under which “ideas and images emerge.” 3 In interviews, he places a great deal of emphasis on the necessity of working with his hands in order to think, which accounts for his preference for drawing-based media. In explaining his unique style, Kentridge speaks of visual knowledge as inherently flawed, in that we only see the present situation at any given moment; the history of what has come before and any underlying issues are lost. 4 This sensibility informs his technique of layering and revision, resulting in complex compositions that convey a sense of the passage of time and a richness of ideas not possible in a single image. In a similar vein, Kentridge frequently uses the word “provisional” to discuss the nature of mark-making, connecting the temporality of a drawn line to the constant change that has become a fixture of modern life.

When making prints, it is therefore natural that Kentridge favors intaglio – a technique that is based in drawing and allows for revision and layering – but he has worked with nearly every printmaking medium and has an intimate understanding of their specific properties and when it is best to use them. In a recent discussion on his printmaking process published in William Kentridge: Trace, Prints from the Museum of Modern Art (2010), Kentridge speaks of printmaking as “a way of thinking aloud”5 and testing ideas, comparing making a print to the process of testing a hypothesis or building a syllogism (a three-part logical argument). Using this metaphor, he likens the matrix to the hypothesis/proposition or major premise, the process of printing and going through the press to gathering data or the minor premise, and the resulting impression to the “proof” or conclusion. Kentridge describes the intermediate process of printing the plate as the moment of truth when the idea is tested “and the hope is that you are convinced by the proof of the rightness of the first proposition.” 6

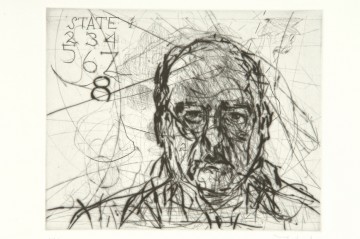

William Kentridge, "State 8," from "Copper Notes, States 0-11," 2005. Drypoint, edition of 14. Plate: 6 ½ x 8 1/8 inches (16.5 x 20.7 cm). Published by the artist, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

Kentridge’s use of the copper plate as a means of rumination is central to two drypoint series, Thinking Aloud (9 Small Thoughts) (2004) and Copper Notes, States 0-11 (2005). Both series show Kentridge’s playful side and aptly demonstrate his pleasure in “being loose and free” 7 with an intaglio plate. These qualities carry through in much of his print work.

By contrast, Kentridge’s politically-grounded prints are more layered and considered in service to his interest in being true to the complexities of the subject matter at hand. As discussed in Susan Stewart’s essay in William Kentridge Prints, Kentridge’s political prints follow in the tradition of Jacques Callot, Francisco Goya, William Hogarth, and Honoré Daumier. In Stewart’s words, Kentridge “has an acute sense of the long tradition of this form as a means of social change.”8 In fact, he frequently uses his predecessor’s work as a starting point for his own prints.9 For example, Kentridge’s first major series, Industry and Idleness (1986), is a group of eight etchings based on Hogarth’s engraved series of the same name. Whereas Hogarth’s images convey a straightforward tale of morality in which the hard worker prospers and the lazy man falls to ruin, Kentridge’s version reflects the ambiguities of contemporary life – the industrious man is undermined by circumstances beyond his control while the idle man prospers due to connections and privilege. Kentridge later completed another series of eight etchings titled Little Morals (1991) with “Goya in mind,”10 in response to the tense transitional years that eventually led to democratic elections in South Africa.

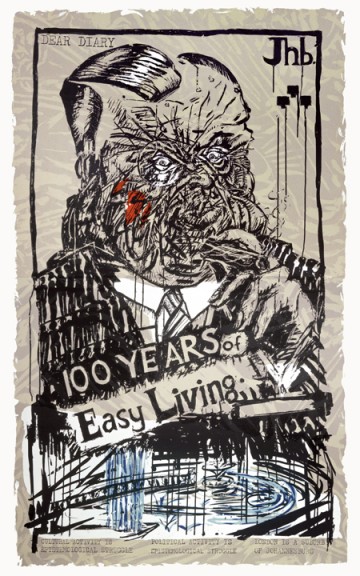

William Kentridge, "Art in a State of Siege," from the triptych of the same title, 1986. Screenprint, edition of 15. Image: 63 x 39 3/8 inches (160 x 100 cm). Published by the artist, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

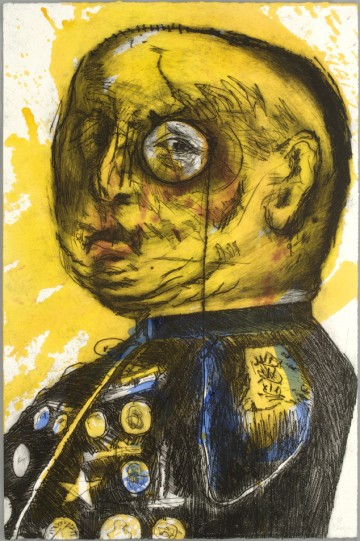

Kentridge’s interest in the political aspects of twentieth-century political art, particularly post-revolutionary Russian Constructivism and Weimar-period German Expressionism, have been examined in depth by curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in her 1998 exhibition and catalogue William Kentridge, where she delves into the artist’s “paradoxical approach to modernism, implying a nostalgia for these utopias while suggesting that they are gone for good, that they have failed.”11 The screenprint triptych Art in a State of Siege (1988) is often held as the embodiment of Kentridge’s contradictory relationship to these art movements by the artist himself as well as scholars. On the other hand, General (1993/98) is a potent and straightforward statement on the type of gross corruption that frequently accompanies military power. As discussed by MoMA curator Judith Hecker, it demonstrates Kentridge’s debt to Weimar-period German artists Otto Dix and Max Beckmann; George Grosz’s smug and gluttonous officials also come to mind.

William Kentridge, "General," 1993/98. Engraving with watercolor, edition of 35. Plate: 47 ½ x 31 ½ inches (120 x 80 cm). Published by David Krut Publishing, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

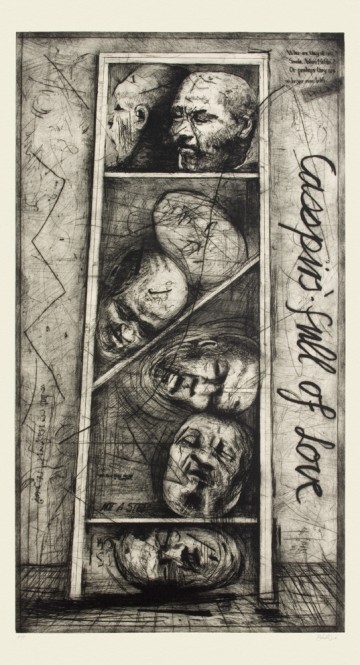

However, not all of Kentridge’s political themes are borrowed. Casspirs Full of Love (1989/2000) is a monumental drypoint and engraving that Kentridge created in response to outbreaks of violence under apartheid rule. A casspir is a South African military vehicle that was used to subdue demonstrators, and the title comes from a mother’s words to her son serving in the military that Kentridge heard on the radio. The theme of procession — a rich allegory representing broad themes of political exile and flight.that informs a large body of his work — is likewise the artist’s own creation. Kentridge’s use of the processional is examined in depth in William Kentridge: Five Themes as one branch of inquiry that has defined his work. Within his prints, this theme is central to the artist’s book Portage (2000), an accordion-fold image comprised of figures in torn black paper marching across disbound pages of a French encyclopedic dictionary published ca. 1906; and the Atlas Procession series (2000), a group of three etchings with aquatint and watercolor in which various figures march in three circles (each a variant of this theme).

William Kentridge, "Casspirs Full of Love," 1989/2000. Drypoint and engraving, edition of 30. Plate: 65 ¾ x 37 inches (167 x 94 cm). Published by David Krut Publishing, Johannesburg. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

Kentridge’s use of layering techniques to suggest multiple ideas and meanings in his prints is discussed at length in Judith Hecker’s essay in William Kentridge: Trace, Prints from the Museum of Modern Art. This approach is most evident in Ubu Tells the Truth (1996-97), a series of eight etchings with aquatint and engraving, and the monumental diptych Learning the Flute (2004) and Learning the Flute (Reverse) (2004). For Ubu Tells the Truth – inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission established in 1995 to investigate human rights violations under apartheid – Kentridge used two plates to superimpose a taunting cartoon-like image of Ubu over a human protagonist who seems unable to rid himself of the troublesome figure. Here, Ubu represents the oppression exerted on individuals by corrupt power.

William Kentridge, Act 3, Scene 9 from "Ubu Tells the Truth" (suite of 8 etchings), 1996-97. Aquatint with etching, drypoint and engraving, edition of 45. Plate: 9 13/16 x 11 13/16 in. (25 x 30 cm). Published by The Caversham Press, Balgowan, South Africa. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

Layering serves a more philosophical purpose in Kentridge’s Learning the Flute diptych (illustrated at top), which he created in connection with his 2005 production of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute. Kentridge was fascinated by the archetypal dichotomy in the story between Sarastro, the high priest of light (representing knowledge and truth), and the Queen of the Night (representing magic and superstition) – creating positive and negative mirror images that complement one another. The opera has long been understood as an allegory of Enlightenment principles; Kentridge here has included several references to knowledge, ideas, and truth, including the light bulb and the all-seeing eye. The scale, stage setting, temple imagery, and Kentridge’s familiar camera reference both the theatrical nature of the opera and the Allegory of the Cave, Plato’s classical parable on the nature of truth and knowledge.

William Kentridge, "Phenakistoscope," 2000. Four-color lithograph on pages from "Bacon’s Popular Atlas of the World" (1951) attached to two gramophone records, machined metal shafts, gear mechanisms, and wooden handle, edition of 40. Image: 11 ½ in. (29.2 cm) (diameter); overall: 31 ½ x 11 ½ x 11 ½ in. (80 x 29.2 x 29.2 cm). Published by New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

Optical effects and devices play a symbolic role in Kentridge’s work – a means by which he investigates the nature of perception and the process through which we see and understand the world. As with other motifs, Kentridge has explored this theme through a variety of media, including drawing, animated film, and editioned work. Phenakistoscope (2000), a multiple in an edition of 40, is the artist’s version of this early animation device traditionally comprised of a rotating disc with pre-cut slots through which the viewer looks to observe a series of related images that appear to move. Kentridge separates the two elements – rotating images and animating slots – on separate gramophone records, resulting in an image that can be read two ways. When viewed alone, the disc at back with the images appears as a moving procession. When the same images are viewed through the slots of the disc at front, the figures do not move, “only passing their burdens from one to another.”12 Similarly, Kentridge has frequently played with anamorphic drawing, in which a distorted image is corrected by a mirrored cylinder. In the lithograph Medusa (2001), Kentridge used the device to play off of the myth itself – Medusa being a creature that could only be safely viewed through a reflective surface. A recent edition, Double Vision (2007) is a set of eight stereoscopic cards with a viewer and wooden box that investigates the illusion of three-dimensional perception that we experience daily.

William Kentridge, "Medusa," 2001. Lithograph on chine collé of pages from Nouveau Larousse Illustré (ca. 1900) to white Rives BFK paper with mirror-finish steel cylinder, edition of 60. Image: 23 inches (58.5 cm) (diameter). Published by Parkett Publications, Zurich, Switzerland. Courtesy David Krut Projects, New York.

As glimpsed here, Kentridge brings us through the full range of his repertoire in his prints. He has spoken of print collections as “metaphors for who we are” 13 – in the same manner, his prints as a collective whole present a portrait of the artist and his concerns. Kentridge’s complex imagery requires a commitment of time, an understanding of literature and history, and careful consideration in order to be fully appreciated, but he rewards the dedicated viewer with bountiful and layered meanings that continue to engage long after the eye has wandered elsewhere.

Notes

- See https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibitions/380; https://moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/964; and Mark Rosenthal, ed., William Kentridge: Five Themes (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; West Palm Beach, FL: Norton Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

- William Kentridge in Dan Cameron, “An Interview with William Kentridge,” William Kentridge (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art; New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001), 68.

- William Kentridge in Susan Sollins, Anything is Possible (documentary film, 53 min., 12 sec.), (New York: art21, 2010).

- William Kentridge in Dan Cameron, “An Interview with William Kentridge,” William Kentridge, 67.

- Judith Hecker, William Kentridge: Trace, Prints from the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 67.

- Hecker, 66.

- Hecker, 67.

- Susan Stewart, “Resistance and Ground: The Prints of William Kentridge,” William Kentridge Prints (Grinnell, IA: Grinnell College; Johannesburg: David Krut Publisher, 2006), 13.

- For further discussion on Kentridge’s interest in his politically-grounded predecessors, see Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, William Kentridge (Brussels: Société de Expositions du Palais des Beaux Arts, 1998) and Michael Auping and Christov-Bakargiev in William Kentridge: Five Themes, 2009.

- William Kentridge in Stewart, William Kentridge Prints, 67.

- Christov-Bakargiev, William Kentridge, 15.

- William Kentridge in Stewart, William Kentridge Prints, 90.

- Hecker, 67.