This is the second of three posts by Daniel Quiles that are loosely based around contemporary art from/in Latin America. — Ed.

Born in 1981 in Spring Valley, New York, Seth Wulsin first moved to Argentina in 2005. Soon after his arrival, he began work on a series of artistic projects based on Caseros, a prison opened in the Parque Patricios neighborhood during the brutal military dictatorship of the 1970s. Demolition had already begun on the structure, which with its history of abuse of political and criminal prisoners alike had become a symbol of the country’s traumatic past. Wulsin ultimately produced two quite distinct projects about Caseros: 16 Tons (2006), in which he created a series of faces by knocking out windows on the façade (which gradually disappeared as the demolition proceeded); the other is a work-in-progress using video interviews with a group of homeless people who later moved into the remains of the building.

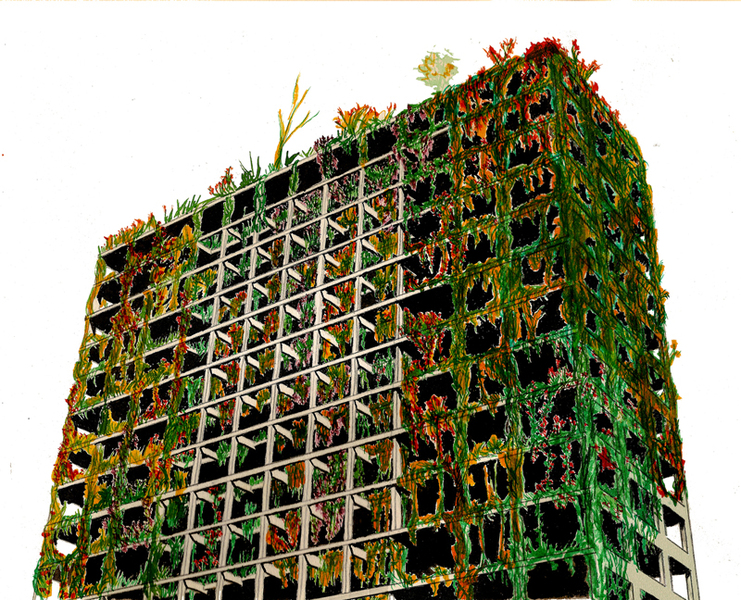

Wulsin’s recent work has included Selva Vertical (2009), a proposal for an unfinished Perón-era building to be overgrown with foliage, and Animas (2010), shown at the Biennial of the Americas in Denver, Colorado, from June to September 2010.

Daniel Quiles: How did you first become interested in the Caseros site as a possible focus of artistic inquiry?

Seth Wulsin: I happened across the Caseros prison building while exploring the Parque Patricios neighborhood with the artist Charlie Higgins. We were interested in working with buildings as raw material for sculptures—not just as inanimate objects or spaces but as living, human ecosystems. Caseros had such an extreme pull on its surroundings that I became totally caught up in its powerful presence, and started focusing more on how to open up dimensions in its ongoing demolition. I was drawn to its scale and its window panels gave me a chance to develop work I’d been doing with reflective pixel portraits, which I integrated into the natural solar and lunar cycles of the building. The more I got to know the site and the stories that surrounded and emanated from it, the portraits seemed like the most transcendent and incisive action I could take on the building.

The history of Caseros was defined by the struggle of the prisoners to gain access to light and to communicate amongst themselves and the outside world, often at the expense of the building.1

I made a rule of not imposing anything on the overlapping structural, historical and bureaucratic mazes of the site. I wasn’t interested in a definitive history, but rather a dynamic, shape-shifting one, rooted in the multifaceted experience of the building. The architecture revealed itself with unfolding layers of resonance through the stories and presence of people who’d had direct contact with the prison. These layers informed the work at every step.

DQ: What role did the demolition play in your work?

SW: Demolition is the architectural element that injected time as the essential medium of the piece. The process of demolition was actually begun by the prisoners to ameliorate the effects of the prison’s harsh design and was only later continued by the state to erase it from view.

The pace of the demolition determined both the bureaucratic time frame for my access to the building as well as the tempo of disappearance of the images once my physical work on the prison was done—an ephemeral architectural performance.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCQzlShtgX4]

Once the demolition was abandoned shortly before completion, the stage was set for the architecture/human relationship of the prison demolition to invert itself. Homeless former prisoners began to occupy the few inhabitable structures that remained, reconstructing their makeshift homes based on methods and aesthetics absorbed from years living in prison.

Living in Caseros Prison from seth wulsin on Vimeo.

DQ: How did the formal elements of the architecture inform your work?

SW: The formal elements of the work had parallels and inverses with the setting of prison in general. These elements also intersected with particular design features of Caseros — defined by its vertical orientation, its bilateral symmetry (and translation symmetry between the 3rd and 17th floors), its lack of natural light and open-air spaces, and its implied combination of extreme isolation and total lack of privacy.

The most basic formal elements of space (reflective, physical, and pictorial) were layered into the work with more abstract elements: the limit, inside/outside, and the dynamic cycle of creation and destruction. These all intersected with the various time cycles determined by changes in light and spatial positions (both cosmic and human), to achieve a rhythmic interplay between the appearance and disappearance of the images.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ego82Rj8ZbE]

DQ: In terms of your more recent project, Selva Vertical, it seems that you are expanding these questions about the built environment into the topics of the current worldwide financial crisis and the ecological crisis.

SW: Selva Vertical will unfold through time, both animating and feeding on the skeletal structure of the building. It’s less an illustration of the inertia of our terrestrial myopia than the creation of a 21st-century nervous system for an unfinished modernist skeleton – an unbuilding.

The skeleton of the Barracas building stands like an implicit monument, though a largely anonymous one, embodying the forgotten history of its own abandonment. As a body it never had musculature, nervous system, a skin — only the skeleton was ever constructed. As a building it was never completed, never had inhabitants. Although it has stood for over fifty years, the effects of time are hard to see. Very few people know that the structure is an unfinished Perón-era social project, although many admire its striking silhouette from the highway or the train.2

People are increasingly aware of a sense that the parallel crises you mention are symptoms of a collision between rapidly advancing methods for political and economic manipulation and systems becoming too complex for their administrators to understand, sometimes offset, sometimes magnified by an underlying tectonic shift in individual and collective human consciousness.

Crisis is the moment when things visibly break down, evidencing something that has been decaying for much longer, but which our collective ability to continue imposing obsolete frameworks on changing reality keeps relatively hidden. This building hasn’t yet reached its moment of crisis in that sense. It has been kept sealed off from its surroundings, never occupied or allowed to serve any purpose, and its structure is still in decent shape.

So while Selva Vertical evokes both a vision of impending doom and abandoned sites overrun by nature, it also puts into play a delicately orchestrated process, where species, colors, scents, and blooming cycles converse and develop in concert with one another. It’s the creation and repetition of a universe, which comes to life by feeding off the slow destruction of its own foundations.

—

Postscript: Wulsin is presently focused on his response to a bizarre incident at the most recent ARTEBA art fair in Buenos Aires in which the right-wing mayor of the city pushed a television journalist into one of his sculptures headfirst, damaging the work.

Notes

1 Gaspar Libedinsky wrote an article in Domus about the “de(re)formation” of the prison architecture by prisoners to serve their own needs.

2 The building is sandwiched both chronologically and spatially by the train track and the highway, the former leftover from the British in the early twentieth century, the latter leftover by the military planners much later in the century.

Daniel Quiles, a guest blog alum, is Assistant Professor of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Pingback: Interview with Dan Quiles from Art:21 Blog « Seth Wulsin