On Johannesburg | “William Kentridge: Anything Is Possible” (2010) Preview | Art21 from Art21 on Vimeo.

It is nearly impossible to talk about William Kentridge’s artistic practice without mentioning – if not devoting entire exhibitions, articles, books, or blogs to – the subject of home. In fact, one rarely sees the artist’s name without the qualifier “South African,” and he himself has said that his work is rooted in his hometown of Johannesburg, where he was born and continues to live and work. It is not surprising, then, that amidst the many influences drawn out in Art21’s William Kentridge: Anything is Possible, dwells a pervading sense of hearth and home.

While home for Kentridge is Johannesburg, the traditional home of artwork — in Kentridge’s images specifically — is the studio, which is explicitly evident in his work. Kentridge employs such diverse media and techniques as drawing, tapestry, torn paper, sculpture, film, and music. “Understanding the world as process, rather than as fact,” his work is a palimpsest of form that almost always bears traces of its making. Kentridge’s artistic practice mines the turbulent history of apartheid and colonialism in South Africa, resulting in a layered picture of both historical events and personal experiences and memories. As Leah Ollman observed, in the aftermath of apartheid that Kentridge experienced, “South Africa was drawing itself, drafting, erasing and reformulating its structures of power, its social relations, and its systems of rights.” Similarly, Kentridge’s charcoal drawings, which most often form the basis of his work, are continually rendered, erased, and redrawn. Inextricably tied to the notion of home is that of memory, and the resultant smudges, shadows, and ghostly lines of the permutations that Kentridge’s drawings undergo exemplify the tenuous and fluid nature of memory itself.

An early point of origin for much of Kentridge’s subsequent work in stop-motion films is 9 Drawings for Projection, a series of nine films that began in 1989 with Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris, which was made through this process of drawing and erasure. In Anything is Possible, Kentridge describes Johannesburg as “a city of dichotomy between leafy suburbs which are man made to a bleak landscape around it, a complete fiction.” He goes on to say that, “the history of the city is of course the history of two cities – the white city and the black people living either invisibly in the city or in the areas around the city.” Kentridge’s work explores this dichotomy, dealing with both home and homelessness, the familiar and the foreign, black and white, reality and illusion, and the opposition between still versus moving image.

Home, family, and an interrogation of identity also inhabits the work of Cape Town-based artist Berni Searle, for whom the theme of origin provides a context for understanding her work. More specifically, being of both African and German-English descent, Searle’s artistic practice often explores the split origins of her mixed racial heritage.

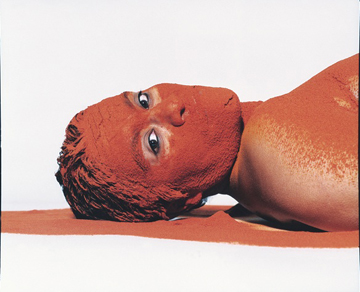

Just as a sense of self permeates Kentridge’s work – through both the transparency of his process as well as through characters that bear strong resemblances to himself and his family members – so, too, does Searle’s own body figure prominently in her photographs, videos, and multimedia installations. In a number of works, such as the Colour Me series (1998-2000), she has enveloped her body with an array of spices, staining her skin various shades of flour white, turmeric yellow, paprika red, and clove brown. While referencing the spice trade, which brought white colonists to the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th century and significantly impacted the history of Searle’s homeland, works such as Colour Me also allude to Searle’s heterogeneous ethnic background, as well as body painting practices that are part of initiation and transition rituals in certain African cultures. Like Kentridge, Searle is concerned with process and transformation, saying, “the self is explored as an ongoing process of construction in time and place. The presence and absence of the body in the work points to the idea that one’s identity is not static, but constantly in a state of flux.”

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03qkfCGfOhM]

I recently saw Searle’s work in my own hometown of Santa Fe, New Mexico – a film titled About to Forget (2005), which is included in SITE Santa Fe’s 2010 Biennial, The Dissolve (Kentridge’s History of the Main Complaint, is also featured in the exhibition). About to Forget, a three-channel video projection, depicts silhouettes taken from family photographs cut out of red crêpe paper. Placed into warm water, the figures of the artist’s relatives, at first immobile, are almost immediately set into motion as the bright red pigment containing their structured forms begins to hemorrhage. Hypnotically dissolving into viscous swirls of red ink, About to Forget examines the notion of connections through bloodlines, while visually calling to mind our universal origins in the mother’s womb.

Both William Kentridge and Berni Searle are strongly influenced by their homeland and their genealogies, and their work continually interrogates and negotiates South Africa’s complex history. Home may be where the heart is, but for artists such as Kentridge and Searle, it is a pulsating, bleeding heart that calls into question the meaning of home itself.