It’s not quite accurate to say that for the past few years I’ve been stalking Kendra E. Roth at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but I have been paying a lot of attention to her work.

While I’d be careful to make too close of a comparison between the Met and the Indianapolis Museum of Art, it is safe to say that both started to spend a lot more resources on contemporary art around 2005. To this end, I was thrilled to have a chance to talk to Kendra about her work there and the recent growth in the Met’s contemporary program.

Kendra is Conservator at the Sherman Fairchild Center of the Met, where she has worked since 1997. She is responsible for the conservation of decorative arts and sculpture of the Nineteenth Century, Modern and Contemporary collection. After completing internships at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Conservation Analytical Laboratories (Smithsonian Institution), she received her M.S. in art conservation from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1996, and a postgraduate Certificate in Advanced Training from the Straus Center for Conservation at Harvard University in 1997. She has worked on archaeological excavations at Kaman Kalehoyuk and Kerkenes Dag in Turkey and Dashur, Egypt.

Richard McCoy: In the U.S., there are no programs dedicated to the training of conservators of contemporary art so many of us have diverse backgrounds. I know that you worked on a variety of projects before becoming the Conservator of Objects for the Nineteenth Century, Modern and Contemporary Collection. Will you start by talking about how you arrived at your current position?

Kendra Roth: I started at the Met when the Greek and Roman galleries were being renovated. At that time, I wanted to focus on archeological conservation and had worked on archaeological digs and encyclopedic museums that had a wide range of collections; so my background was in conserving artworks from all sorts of cultures, made from a variety of materials.

In 2007, after the Greek and Roman galleries opened, the conservator who was covering the contemporary projects and our director announced their retirements. So there was an opening in the Modern and Contemporary Art Department and at the same time, a shift in the department was precipitated by Gary Tinterow becoming the Engelhard Curator in Charge of the new Department of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art in the Summer of 2004. I was excited to take on this new position, but a little frightened because it was unnavigated territory, so to speak.

By the time I started in 2007, it was already a dynamic time in the department as both the curator and the new director, Thomas Campbell, wanted to shake things up and bring in more contemporary art—not just more of the modern classics, if you will.

So, that’s the way I ended up taking the position: I was in the right place at the right time. And I’ve not regretted it ever since.

RM: How many conservators work on the modern and contemporary collection?

KR: Well, each curatorial department at the Met is kind of a museum unto itself. We have 17 curatorial departments and each has dedicated conservators with specialties related to each curatorial department. I collaborate with a conservator of furniture paintings, paper, and sometimes those specializing in photographs and textiles. I also work closely with the department’s collections manager, Cynthia Iavarone.

My office and workspace is downstairs in the Objects Conservation Department with all of the other objects conservators. There are currently 28 of us in the Department, not counting fellows, interns, and our administrative support.

Kendra Roth's conservation workbench at the Met. Working behind the Sol Lewitt is Conservation Graduate Fellow Emily Hamilton. Photo courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

RM: Oftentimes here at the IMA, it is hard to define an artwork by the terms conservators use to define their specialties: objects, paintings, works of art on paper, etc. Generally speaking, this requires that I work collaboratively on projects with a variety of conservators. Is it the same for you?

KR: Obviously in contemporary art, we get the weirdest cases and are responsible for conserving artworks made of a huge variety of materials. A lot of the time, I’m doing more troubleshooting and finding the right people to do the job rather than doing it myself. If there’s a part of the project that’s beyond my scope, I’m always willing to call in a paper, objects, or other conservation specialist, not to mention those outside of the conservation community.

In house, I’ve found that the two conservators who are faced with similar challenges as me are the ethnographic conservator, Christine Giuntini, and the conservator for the Costume Institute, Chris Paulocik. Not only do we all work with artifacts that are made from a huge range of materials—be they from ceremonial garments or Madonna’s clothing and accessories—but they also require being approached with sensitivity to their function and purpose, which can be cultural, religious, or social commentary.

RM: This reminds me of a great quote from Jill Sterret who is the Director of Collections and Conservation at SFMoMA. In a recent interview published in the Getty Newsletter she talked about how conservators of contemporary art are different than those that work on, for lack of a better phrase, “traditional art.” She said:

There are skill sets that serve a more traditional mode of conservation, and there are skill sets emerging that underpin success for people working with contemporary art. And they’re not always one and the same. Conservation has always called for analytical thinking, but now we’re looking for abstract thinkers who are comfortable synthesizing solutions. Rather than master practitioners, we’re looking for people who are master facilitators in many ways. That demands skills that are different from those required to restore a Rembrandt spectacularly.

KR: I think that’s very well said, and very true. Back when I was doing traditional conservation, I would end up repairing or joining fragments of an ancient object all by myself. Now I feel like more often than not, I’m working as a project manager; I’m making sure the work is being done by the appropriate people. So it’s my job to do the detective work, to ask the right questions and to find out who the right people might be.

Sometimes that right person is the artist, or sometimes the foundry that made the work or some other fabricator. It could be anyone — even, say, an auto mechanic or other tradesperson, depending on the situation.

But I’m definitely the odd ball down here in the Objects Conservation Department; the other conservators spend a lot of time at their work bench, about 50% or more of their day. I find myself on the phone, researching things online, or corresponding with people via e-mail. I spend more of my time in my office which, as a conservator, sometime leaves me to wonder what I’ve done all day.

RM: I know that feeling.

KR: I am getting things done, I am moving projects forward. I just don’t have the same kind of physical things to show for it, like the other conservators.

RM: I just spent the morning helping to install our new Tara Donavan acquisition that was commissioned for her recent IMA exhibition. While I was integral in putting that together, few would call that work a “conservation treatment” or “bench work,” but clearly it was an important thing to do.

KR: I definitely spend more time in the galleries now than I did when I was working as a traditional conservator. I spend a lot of time watching installations and deinstallations. I’m always checking on something that may have been damaged, or isn’t working properly.

RM: That’s an interesting point. I’m certain I spend more time in the galleries than I do working at any kind of conservation bench.

KR: You can think about it logically: contemporary artworks are newly-created things, they shouldn’t be broken yet, but because they are made of materials that are often new to art museums, they require a lot more study and consideration. It’s a different kind of problem solving.

RM: Well, then, thinking back to your noted involvement conserving the Montelone chariot, what are the conceptual or differences in your approach to artworks that are being made today in comparison to those that were made in ancient times?

Kendra Roth and mount specialist Fred Sager working on the Monteleone Chariot. Photo courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

KR: Even though the materials might be the same, the biggest difference in the conservation approach to contemporary artworks versus traditional ones is that traditional conservation work intends to freeze the physicality of the artwork in time. Traditional artworks aren’t meant to change once they enter the halls of a great museum. They shouldn’t deteriorate, corrode, or have the paint flake, so conservators work to fix and “freeze” these artworks.

Whereas with contemporary artworks conservators are often charged with preserving an idea or a concept. This is totally different. We face questions like: What did the artist really want to express with this artwork? What did the artist want to say by creating this artwork?

Preserving an idea versus preserving a tangible object that is frozen in time requires a different approach and different considerations.

RM: Conservators working on modern and contemporary artworks are playing from a position that is different from traditional conservators. Many contemporary artworks are already changing by the time a three month exhibition is over. In this way, the traditional conservator’s hand is forced.

KR: So, that’s when conservators are put in a position to come up with reasonable solutions instead of hold on to these fixed ideal situations. If the artwork was created by an artist who is still living then you can go back and discuss a preservation methodology.

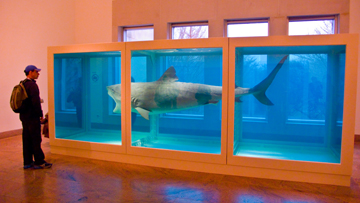

RM: What better piece to think about these ideas than Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, which just left your museum after spending three years there. While I know that you were not involved in the well-documented replacement of the first shark, can you talk about your involvement in displaying this artwork at the Met?

Damien Hirst's "The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living" on view at the Met. Photo by jwilly on Flickr.

KR: With that piece, there were three major issues we were dealing with: 1) the volume of liquid in the gallery and its weight, which is approximately 27 tons 2) its dimensions: over 17 ft long, 7 ft high and 6 ft wide, and 3) the toxicity of the formaldehyde .

We had to re-enforce the floor where it was exhibited—if you remember it was on the second floor of the galleries. It was so big that we couldn’t get it into the gallery through the freight elevator. Installing the piece was a big, collaborative project that involved many people inside and outside of the museum.

The artwork was brought in the back of the museum through the formerly-public entrance in the Petrie Sculpture Court, which looks west out into Central Park. From there we hoisted it up into the second floor and moved it through a deconstructed wall then we transported it all the way through our galleries on the second floor to its exhibition space by the window.

Moving it through the galleries meant that we had to move all of the artworks in its path. It went out roughly the same way so it was a huge production in both directions and required a huge number of people, including a team from Damien Hirst’s studio, to accomplish successfully.

We also had to prepare and think through what would happen if the tank started to leak in the galleries. That could have been a real disaster to let that amount of liquid loose. To mitigate the leak risk, we installed cameras in gallery, exhaust systems to deal with the toxicity of the formaldehyde, and developed a first-responders protocol in the event something went wrong. In the end, it all worked smoothly and the piece was exhibited very successfully for three years.

RM: When I last visited the Met I spent some time with your new kinetic piece by Jean Tinguely, Narva, from 1961. There seems to be a mechanism that reduces how often it can run. Can you talk about how that piece works?

KR: We have a built-in timer so no matter how many times patrons stomp on the little pedal in front of the sculpture, the motor will not start again until a few minutes pass. This way it will not run constantly and thus limit the wear to the sculpture.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MXvdJYlYOj4]

RM: That work is the kind that I think conservators often worry that someone is going to get hurt on or damage, but I believe patrons respect works like these a lot. Have you had incidents with patrons interacting with it negatively?

KR: Well, I think in general they are more fascinated with the little button that makes the sculpture turn on. They see a button and they want to push it. We also have an emergency stop switch on the sculpture, but we found that people want to push that button too, so we had to place a cover over it to mitigate a sort of button frenzy.

Right now we’re re-visiting that piece. I’ve given the research project of developing protocols for display and function of that artwork to my intern, Emily Hamilton. This project was precipitated by a visit from the conservator from the Museum Tinguely, Reinhard Bek, who was at MoMA completing a research fellowship on kinetic sculptures. When we acquired that piece, it was immediately put in the gallery for display so now we are considering how it’s going to live its life better here at the Met and be sensitive to what Tinguely intended.

The more we think about that piece, the more questions arise. We want to make sure it’s running at the correct speed, shaking correctly, and sounds right.

RM: Recently I spoke with Karen te Brake-Baldock about the symposium Contemporary Art Who Cares?, which was co-sponsored by the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (INCCA). There is now a North American branch of INCCA, which I know you’re involved with. Will you talk about what you’re doing with INCCA-NA?

KR: The mission of the association is to bring together collections professionals to share information about artists and artworks.

I joined the INCCA-NA Program Committee in 2008, when Gwynne Ryan of the Hirshhorn Museum took leave to give birth to a set of beautiful twins. We’ve completed a lot of programs, many of which focus on interviewing or speaking to artists about their artworks. Right now, we’re collaborating with the Tony Smith Foundation and the Menil Collection to develop a program next spring around the care of Smith’s many outdoor sculptures. But at the same time, we’re developing a model by which conservators and everyone who has a stake in caring for these artworks can share information about how to care for them correctly.

The goals of this project are to bring together a critical amount of information around Smith and to gather the most experienced folks that have worked on his artworks to brainstorm ways in which we can share information about it. At the same time, we want to expand the project to become a global effort and open to a wide-ranging variety of participants online platforms. We hope this project become a repeatable format that can be applied to other artists.