Since moving away from Chicago this past summer, I’ve seen how Chicago and the Midwest have influenced my work, as well as my work ethic. The spirit of experimentation and collaboration run very deep within Chicago’s art veins, and I’ve seen how Midwest hospitality has infiltrated even the toughest skinned “coastal imports.” With these in mind, I’m curious how artists working online – in a non-specific spatial setting – have either engaged or adjusted their Midwest sentiments (if any) within a global network.

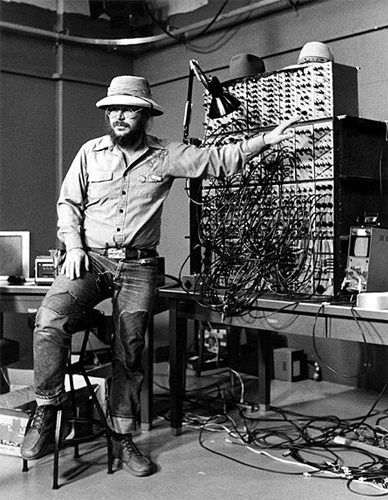

A good starting point is to gesture toward the rich history of media makers that planted (or nurtured) the powerful seeds that fostered a strong relationship between technology and art. Analog computer wizards like Phil Morton and Dan Sandin drafted The Distribution Religion to provide blueprints and schematics to build a real-time image processor that could manipulate video signals into strange and beautiful psychedelia. Morton and Sandin influenced a whole generation of video makers, and later, digital artists working with experimental media and subversive forms of distribution.

I asked several net artists if their practice has been influenced by living in the Midwest, and I received a wonderful variety of responses. Although working online has “freed” several artists from the limitations of a bloated or overcrowded art market found on the coasts, some argued that this liberation is not unique to the Midwest and that artists internationally are finding ways to create and distribute their work without the cumbersome (and what some would call slow) commercial gallery system.

Bea Fremderman wrote to me:

Unlike most traditional mediums that have a direct conversation with the place they were made in, digital mediums rely on a set of predetermined tools, which are universal in aesthetic regardless of locale. I want to believe locale has little to no effect on my practice since giving creative sensibility to a city seems trite and useless in regards to digital work. But subconsciously, we are in many ways affected by our surroundings because culture affects us all.

As Fremderman concedes, living in the Midwest had some tangential influence in how one works, but most artists I asked explained that the immediate community of other net artists and peers played a larger role in the formation of their work then any over-arching middle-American sentiment.

That being said, I’d argue that there are themes that can be traced through several artists’ work, and that these similarities could be attributed to living on the third coast. One common thread is observing how some artists re-imagine/re-investigate art history as an active agent in contemporary digital media. Mark Beasley, Chris Collins, Brian Khek, André and Evan Lenox, and Micah Schippa have all contend with the weight of art history, and all approach this “burden” with an eager playfulness.

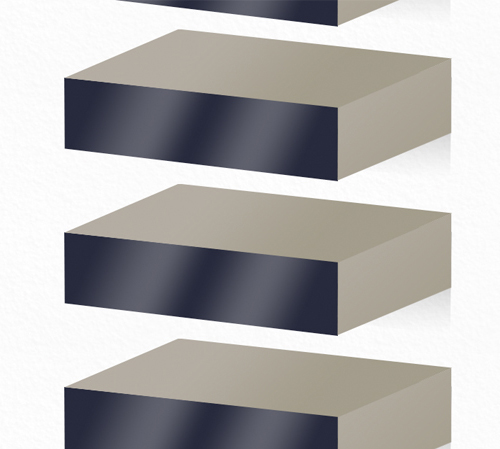

In several different iterations of Beasley’s work, he transcribes post-minimal “instruction set” pieces by artists John Baldessari and Vito Acconci in an attempt to relate these simple executions of commands to similar environments found within computer code. Collins takes the sublime aspects of Donald Judd’s shelves and turns them into an infinite browser scroll to suggest how our post-manufacturing culture can readily emulate what was once thought of being unique or potentially overly-precious.

Where Beasley and Collins discuss particular works within the canon, the Lenox borthers, Khek, and Shippa play with a broader index that art history has ingrained in our visual culture. The Lenox brothers, occasionally under their Twincraft moniker, undertake an exploration of ancient Greek and Roman architecture in their piece 17° SOUTH ⊗ 149° WEST to highlight some of the hollow utopian prophesies that have surrounded the space of the web (and likewise gesturing toward the platonic ideas of pure forms). They attest that the influence of the Midwest on their work has “not immediately result[ed] from networking, but rather from face-to-face interaction and discussion. Responding to utopic desktop wallpapers, online advertisement banners, and social interactions all become methods of depicting an attempt to subsist in an idolized state.”

Schippa uses the history of Abstract Expressionist painting in his collaborative work with Parker Ito, (former Chicagoan and art-history junkie) Jon Rafman, Tabor Robak, and John Transue, for a digital painting project called PaintFX. Although it’s hard to distinguish the distinct “style” of each participant in the project, the prolific content generated is a deliberate defacing of the traditional sole-artist-as-genius model that can dominate the gallery.

Khek’s work could almost be observed as a synthesis of the pillars of ancient Rome and the color fields of Rothko. One views these art historical examples along side empty office spaces and 3D renderings of cubicles. The associations made between the everyday architecture and art from history and contemporary culture create a void which Khek fills with textures and geometries that hyperlink desperate sublime spaces or a “scattered topographpy.”

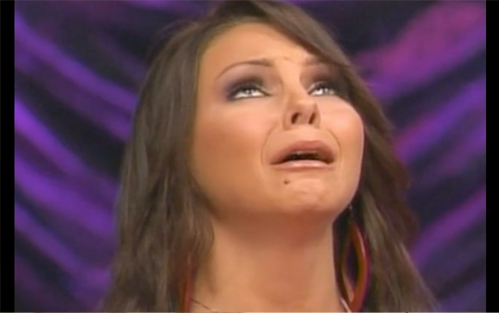

Although subversion and disruption of art history creates a significant tie between artists in the Midwest, another common bond can be found in the appropriation of popular media’s depiction of powerful emotional or phenomenological moments. Jesse McLean, who works more in experimental video, pairs reality television contestants being asked to leave the show (and their emotional breakdown) with a California earthquake captured on live TV (like morning news programs). The tension that McLean creates here is between how we document and exhibit the emotional duress of our media culture — how the availability of experiences filtered through digital platforms (like DVRs in McLean’s case) can be both overwhelming and unpredictable.

Fremderman approaches these personal watersheds of emotional development through using a visual vernacular common in popular youth culture. The collages and reconfigurations of what look like high school portrait photography for yearbooks creates a dialogue between different versions of artificial presentation of self through one’s formidable teen years. The difference between the controlled area of the posed portrait or landscape and the chaos in punk/zine culture creates a disquieting composition without perpetuating the saturation of image-making found in mass media.

Regardless of content, Fremderman employs a reserved tone that I think is also emblematic of Midwestern art practices. “I think the… general Midwest disposition (low cloud ceilings, long winters) lend to a more introverted/reflexive practice,” is how Beasley describes the contemplative nature that many Midwestern net artists employ within their work; this is an interesting paradox when considering the extroverted tendencies found in online social networks. Collins attributes this to lack of involvement his immediate local community has in any art scene:

Very few of my friends in town are artists. None of them make similar work to mine. I have to explain the things I do and why I do them to a lot of different people. Rather than being engrossed in a culture where the value of art is a given, I have to defend it, justify it, and combat indifference. It can be frustrating, but I believe this makes my work stronger, and my choices as an artist more informed.

Some of this indifference that often occurs between those “within” an art circle and those “outside” lies in the acceptance that Chicago and the Midwest are not considered international cultural landmarks. As a result, I think one finds more projects in Chicago that are inherently invested in the idea of community building and DIY participatory events (see projects like Temporary Services and InCUBATE).

I’ll close with a thought that Micah Schippa offered in his reply to my initial inquiry:

Chicago has long been under the radar, a peripheral player in the art world. Anyone or thing happening here is generally classified as anomalous. In the past, it was simply the lack of access to highly pertinent conversations that were happening in other larger cities (Paris, NY, LA, Berlin, Tokyo, London etc). But the sci-fi-ish amount of access and connectibility we now have has leveled the ground upon which all our idea stand. Geographic borders have not dissipated, they have been augmented, positively enhanced, or rather they have become highly permeable membranes where once were walls. Also, perhaps this is all wrong and the internet has taken the place of the symbol of NY in the art world. Perhaps those unfamiliar with this info-megalopolis will be completely left behind, excluded and ignored… [in other words] will the away-from-keyboard-world [become] the new Midwest?

Pingback: Center Field: Is Locale Needed? Netart in the Midwest « Jesse McLean

Pingback: Center Field | Is Locale Needed? Netart in the Midwest : Bad at Sports

Pingback: Net Artists Midwest: Is locale needed? | TRACK

Pingback: links for 2010-11-24 « links and tweets