Albert Bierstadt, "View of Donner Lake, California," 1871–1872. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 29 1/4" x 21 7/8". Courtesy the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Albert Bierstadt bathed the Sierra Nevada in heavenly light while Ansel Adams photographed Half Dome as though it were on the moon. Many artists depict California’s natural features as mythic and otherworldly. David Wilson’s landscapes run contrary to this impulse. The contemporary Northern California artist makes the state’s geography humble, knowable, and intimate. Although suggestive of wild places, the sites he draws are typically within five minutes of a major city. While Hudson River School painters such as Bierstadt proposed that nature was a place of heightened consciousness and sublime intensity, Wilson presents it as being down the street. His is a wilderness accessible by bus.

The artist’s installations and gatherings, often unsanctioned, mostly outdoor, continue his exploration of place. In some cases, they’re a direct extension of his two-dimensional work. Here, I talk to the artist about California, the Heal drawings, the Memorial Fort, and his summer 2010 residency at the UC Berkeley Art Museum.

Victoria Gannon: When did you move to California and why?

David Wilson: I moved to California in Fall 2005, shortly after I graduated from Wesleyan University, in Connecticut. I grew up on the East Coast. I had never gone inland, and some friends had been talking about coming out here. One friend in particular was really preaching the West Coast.

VG: How was she was selling it?

DW: She said, “We’ll go to Oakland and get a warehouse space, and it’s so cheap, and there’s really great people out there, and it’s so beautiful and the hills.”

My first visit, I went to Stinson Beach, and I went to the Berkeley hills, and I went to LoBot, that warehouse and gallery in West Oakland. I had this sense that this is an area that’s very involved with its landscape, which is really exciting to me, especially coming from the East Coast, where towns are so locked in. The idea that within ten minutes of driving the city would transform to just being beautiful and wild was very appealing to me. That sold me.

Wildcat Canyon Regional Park; Richmond, California. Photo courtesy size8jeans (cc).

The first year or two I was here, I spent all my free time going off in the hills and trying to get a little bit lost. I would follow my instincts, and then there would be a moment where I’d know it was the right time to sit down and draw what I saw. A bunch of drawings, mostly smaller drawings, came out of that process. Then there was a moment when I naturally started making larger drawings. I did one of Briones Regional Park. That was one of the first drawings I worked on over a period of time, rather than in just one sitting.

VG: Was it all one piece of paper?

DW: I figured out this system of working on sections. I’ve always enjoyed working on found paper and started collecting papers from record sleeves; some of them don’t have perfect edges and don’t have holes in the center. I would bring out as much as I could fit on a board. Soon after that, I had a simultaneous sense of feeling ready to take on a truly large drawing and experience of being in a place, and then my dad was diagnosed with cancer.

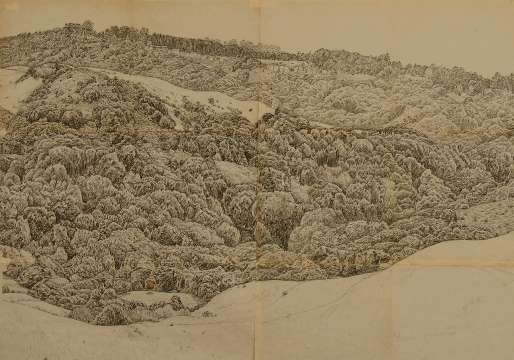

David Wilson, "Heal," 2008 (detail), charcoal pencil on found paper, 42" x 144". Courtesy the artist.

That was when I started a drawing that I spent a year on (Heal, 2008). My dad was sick for two years (before passing away). The first year was a year of confusion; there was this sense of “He’s just gotta heal.” That was kind of the mantra, and that drawing was a way to channel that and think of him and his healing and give myself an anchor. When I finished that, I needed to continue because it was still happening. So I started over, I returned to the same spot, which is in the Richmond hills, and started to do the same drawing over again with a brush. That was Heal Again (2009).

VG: I really like the seriality of Heal and Heal Again; you can tell that you drew them on multiple pieces of paper over a period of time. For me, it references emotional healing, which happens incrementally. It’s a slow process, and it’s only over a long period of time that things come into focus again. How did the Memorial Fort come out of that?

DW: When my dad did die, I still wanted to continue visiting that place, but just sitting and drawing really took a lot. It was a real struggle. So one day, I left the board and took a walk. I went back to this grove that I had really enjoyed. And I realized I needed to do something physical, and get into some physical labor. Sometimes you need to sit and have a meditative experience, and sometimes you need to carry heavy things and move stuff and sweat. And so the fort began.

VG: Was that the first time you had done something like that as part of your art practice?

DW: I guess so. I had always thought about space, in terms of responding to spaces and the way they can support groups of people. That was the first time I had tried to build something.

VG: You were creating a shelter or a refuge. There’s something obsessive about it.

DW: There was definitely something obsessive about it. I would pick up all these branches and carry them all over the hill, and do it over and over. It’s like nesting.

VG: How long did it take you?

DW: I devoted a summer to it. I just went out there every day. I put everything else in my life on pause. Sometimes people would come out there and help me.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zImTnt1JsJM]

VG: How did you decide that you wanted to share it?

DW: A year and a half earlier, the Hot and Cold (a zine published from 2002 to 2009) guys, Chris Duncan and Griffin McPartland, had invited me to participate in a group show at Baer Ridgway Exhibitions and in their zine. The idea of organizing something was out there. (Heal Again was included in the exhibition and directions to the fort were distributed in the Hot and Cold zine.) It was a really good lesson for me to make things meaningful. I could’ve said, “Sorry guys, I’m too out of it, I can’t do it.” But actually, (the fort) was exactly the thing that I wanted to share; it was exactly what I wanted to bring people together around at that moment.

David Wilson, "Memorial Fort." Courtesy the artist. Photo: Terri Loewenthal.

VG: I like that you insist on the legitimacy of a personal meaning in the artwork. Most artists aren’t as disarmed; they have a big concept or the work is ironic, but it’s very rare that an art piece is acknowledged as coming from a very personal place. I like that you insist that that’s enough of a meaning for an artwork to possess.

DW: That’s all that I know, in a lot of ways.

VG: It seems the most obvious approach. I can read about other subjects, but in a way, my own experience is the only thing that I’m an author of. So what happened when everyone went to the fort?

DW: Well, for me, it was a memorial, but I didn’t want other people to be attending a memorial for my dad. That’s not what it was about. Still, I wanted it to be a ceremony, a celebration but also a reflection.

"Memorial Fort Gathering," September 19, 2009. Photo: Terri Loewenthal

I called my friend Daniela, who sings in a project called Snowblink. She’s a cantor and sings Jewish prayers and leads services; she has the most powerful, beautiful voice. She composed a series of pieces, and I recorded them. I had this tape recorder behind my back blocking the wind, and she sat behind me singing. Then my friend Lucas rigged up this pulley system in the fort. During the gathering, we put this cassette player on a pulley in the center of the grove and just let Daniela’s prayer songs play. That was the heart of it.

VG: That sounds like a very gentle way to pull people into having an experience rather than telling them to do something.

DW: There were no words, really.

VG: I’m interested in the way the social gatherings fit into the rest of your work. That’s something you’ve been doing for a while?

DW: They began a year after I moved here. I was doing a lot of exploring. There was a few in the Oakland hills; the first few were about making maps and sending out invitations. It was more about how to get people to a place.

VG: There’s an element of shared secrecy to that. Were you presenting them as social practice?

DW: No. It’s great that you can arrive at ideas from different perspectives, and those gatherings were coming from the perspective of the music community. They made sense especially when a lot of people are setting up house shows, or shows in a gallery.

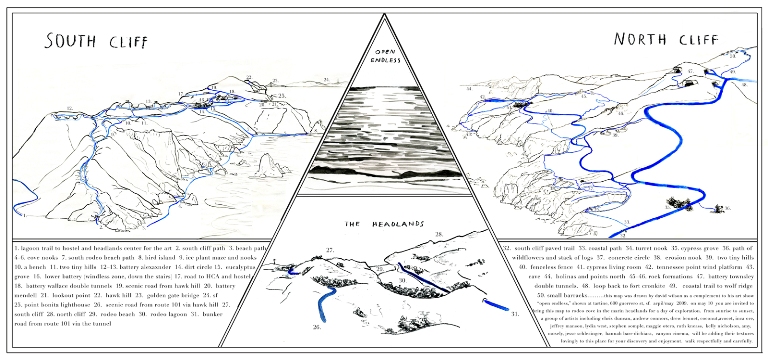

Most of the gatherings were in places where I had been making drawings. Two years ago, I had a show at Tartine. I had done all these drawings of Rodeo Cove, in the Headlands. That was one of those primary places that was the first place that I had got in the ocean, when I first moved here. Then I made a map of the cove and organized this event. There were ten or so different artists who had made installations all around the cove, and there was this day of exploring.

"Headlands Map for Open Endless Gathering," 2009. Photocopy edition of 300, 8" x 17".

VG: When were you approached about the residency at the Berkeley Art Museum (BAMPFA)?

DW: Last fall. I feel like my most exciting and unique experiences were the ones that happened on my own terms, so it was exciting to think about how to make this residency unfold in a similar way. I began thinking about treating the museum as a place to learn about, to treat the architecture the way I treated the outdoors in my other projects. I could treat the museum and the building and the surroundings as the new place I was learning about. I spent a lot of time at the museum making drawings and getting to know it. It’s an incredible building, as space goes.

VG: What was the Sun Ceremony?

DW: I liked that the fort had a sense of ceremony. In the spirit of that, I saw the Sun Ceremony as an opening ceremony for my residency at BAMPFA, opening this place up and opening up this season, and opening up this project, for me. My friend Chris (Duncan) had been working on this project all about drumming at Kala Art Institute; I started to think about the idea of having lots of people create many sounds together. So I pitched it to Chris. And I’m always excited about centering ideas on celestial things like the sun and the moon, so it was a pretty easy sell. He had called his project the Sun, and I had charted out some of my projects with the moon, so we just focused on the sun.

"Berkeley Art Museum Installation," July 23, 2010. Photo: Myleen Hollero.

Then Chris and I and a few other people worked together to make this sun object, a papier-mâché globe that was eight feet in diameter. I teach at an elementary school, so I use papier-mâché a lot. This became a central object that we put on a pulley, and it would go up and down over the course of the show and for the Sun Ceremony. There were six or seven different people with overhead projectors with color wheels teamed up around the museum; they would shine their different-colored light onto the surface of the sun. I would hold different-colored cues, and if I held up a yellow circle, all of the projectionists would switch to the yellow and the sun would be yellow.

"Berkeley Art Museum Sun Ceremony," 2010. Courtesy the artist.

Then we made this sheet music that would coordinate colors with actions, so yellow meant just drumsticks, and orange meant just drums. In ways, it was kind of a release, and kind of a freak out in a lot of ways. For a lot of people it was nice to just do something that is a little bit wild, all together.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HObFW3ulrP0]