ZKM | Museum für Neue Kunst, ©2010 ZKM

When asked a few weeks ago to accompany a friend to Karlsruhe earlier this month for Elmgreen & Dragset‘s opening of Celebrity: The One and The Many at ZKM, I jumped at the chance to participate in my favorite activity: traveling to meet an institution whose net presence I’m familiar with. So while the column’s next post will chat up Berlin-based artists Elmgreen & Dragset, this week takes a turn out of Berlin to look at ZKM ❘ Center for Art and Media, Germany’s bastion of intermedia arts. Founded in 1989, the Center for Art and Media has championed digital media, acting as a leading force within the global community in exhibiting, collecting, and conserving works in the days before most museums thought about digital database systems. So what better timing to get acquainted than during an opening and the ZKM’s hosted symposium, The Digital Oblivion?

Coming from Berlin, the first thing one notices about ZKM is its sheer size. And then, for those of us often confused at Germany’s lack of digitization, the automatic question is: “Karlsruhe, really? The seat of the German Federal Constitutional Court?” (For those unfamiliar with the German legal system, it’s a lot of paperwork). Yet, it makes sense. ZKM is home to to a core group of arts-related practitioners focused on developing theoretically sound strategies for long-term institution building. When asked, museum sources will tell the story of how in 1988, a committee of professors, politicians, and nuclear researchers put forth Konzept 88, which outlined the creation of a research institution for the emerging field of media arts technologies. Following the Center’s 1997 move into its current residence, the roving center transformed into ZKM ❘ Center for Art and Media, a think tank whose vast programming is a testament to director Peter Weibel’s philosophy that media art is not entertainment. But as it turns out, the history is a lot less stoic than it sounds: until reunification, Karlsruhe was Germany’s Internet capital (Universität Karlsruhe sent out the nation’s first emails in 1984) and from 1980-1994, the munition factory was outfitted with squatting artists’ studios. Though the institution’s press department would eschew this kind of language, it’s safe to say that ZKM was built out of a whole lotta cyber love. And no where is that more apparent than in Peter Weibel and Berhard Serexhe’s exhibition, IMAGINING MEDIA@ZKM.

Celebrating the Center’s 20th anniversary, the exhibition features a staggering 152 artists and ca. 150 works from the museum’s collection which have been diligently recreated for permanent display. The exhibition ranges from flashing LEDs to 3D immersive environments, with some of the most playful works hailing from artists who participated in the institution’s now defunct festival, MultiMediale (1989-1997).

There is Frank Feitzek‘s prognostic joke on Second-Life, Cyberbraü, a two-piece beer vending machine in which one side is a traditional coin automat, while the other trades coins for the chance to virtually fill up a beer that you’ll never get in real-life.

Agnes Hegedüs, “The Fruit Machine,” interactive installation, 1993.

Or Agnes Hedegüs’s 1991 work, The Fruit Machine, which allows gamers to piece back together a broken 3D slot machine ball or reel in order to win fake cash.

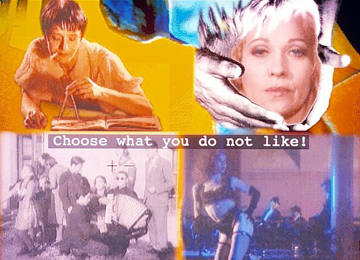

artintact4 (Marina Gržinić, Aina Šmid, and Steffan Ruyl Cramer), "Troubles with Sex, Theory, and History," Institute for Visual Media, 1993.

While some works toy with economies of visual gratification, others like artintact4’s Troubles with Sex, Theory, and History and the revived pieces from the 2005 exhibition 40jahrevideokunst.de illuminate how evolving time and virtually-based mediums create vital platforms for exploring questions of politics and possibility in Central Europe.

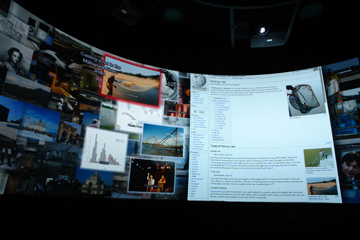

Bernd Lintermann, Torsten Belschner, Mahsa Jenabi, Werner A. König, "CloudBrowsing," 2008/2009. Forschungsprojekt und interaktive Installation für PanoramaScreen, © ZKM, Foto: Sónia Alves.

It is the impetus to salvage works like these from endangered and extinct digital mediums that helped fill-up Karlsruhe’s hotels that weekend, and to turn the Kaffeehaus conversation from aesthetics to institutional strategy during The Digital Oblivion, a symposium whose three year multi-party parent project, digital art conservation, brings together museums, universities, and art spaces from across the Upper Rhine Valley to discuss the ethics of digital media conservation. The symposium’s speakers swiftly attacked the typical laundry list of archivist agenda items with trumpets of grave concern wired on diplomatic language that I hadn’t heard since meeting with UN-affiliated cultural educators in Uganda. But in spite of the ironic undertone of preserving works created by ideologically fatigued underground movements with governmental tools, I felt incredibly grateful to the librarians and administrators in attendance who dedicate their time to making artworks available for generations.

Topped off with Elmgreen & Dragset’s Celebrity: The One and the Many, the sojourn to ZMK is well worth the trip. And while you’re there, don’t miss Baden-Baden.