-

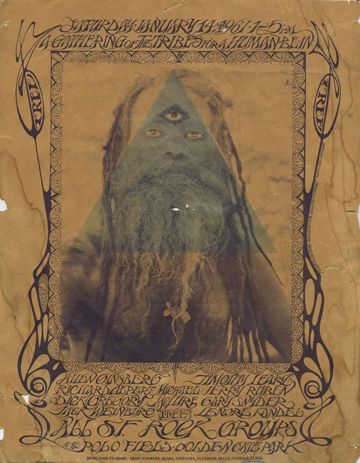

Handbill for the Human Be-in, which took place in January 1967 in San Francisco. Image courtesy of Oldhandbills.com.

Every few decades, people decide it’s a good idea to move to California. First, it was for the gold. Then aerospace technology, then Los Angeles. In the 1960s, it happened again, as idealistic teenagers arrived in San Francisco to build a new world in which previous generations’ hang-ups didn’t apply. They joined ongoing protests at UC Berkeley, where students had seized a parcel of land to create a park for the people. They held be-ins against the verdant green of Golden Gate Park, believing their positive energy had the power to halt a war thousands of miles away. They attended West Coast versions of Woodstock, where Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin performed.

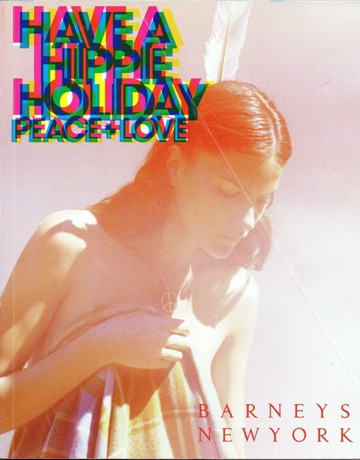

Though vibrant, the summer of love couldn’t last. Fall came; the hippies got older. Many succumbed to drugs, and many “sold out,” choosing careers and capitalism over their youthful radicalism. The movement petered out, but it did inspire a psychedelic, romantic visual culture and sensibility that lives on in Northern California. Think mandalas, geodesic domes, sacred geometry, and magical pyramids. Now divorced from their radical origins, such signs currently stand in for a generalized mysticism, a vague allusion to mystery and free-spiritedness that is peddled in stores and incorporated into artwork.

"Have a Hippie Holiday," Barneys New York 2008 catalog. From the collection of Carol Anne McChrystal.

How do insights get reduced to commodified images? When is the moment that radical possibility becomes disappointment? Working as Nightmare City, Carol Anne McChrystal and Keturah Cummings make digital-based work that addresses these moments of unfortunate transition. With an aggressive aesthetic, the duo’s work embraces repetition, disorientation, and illegibility, pushing viewers into a zone of discomfort where images lose their commonly understood meanings and re-emerge with new significance. At the core of their practice is an interest in images and their signification. Again and again, they ask: how does an aesthetic assume a cultural value, and how does it lose that value and gain a subsequent one?

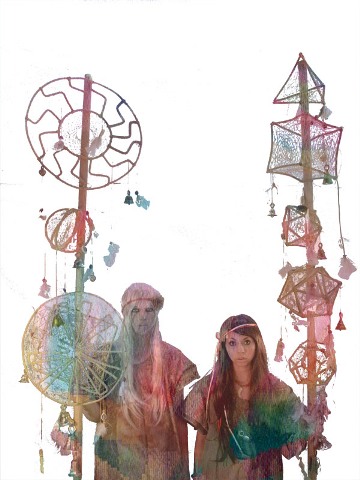

Nightmare City, "Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde," multimedia, 2010. Courtesy the artists.

This grim trajectory progresses from the movement’s most idealistic moments―a gathering of twenty thousand people in a “union of love and activism”―to its darker manifestations at Altamont. Their choice of locations plots a pessimistic map that examines the relationship between idealism and violence; its progression suggests that anything taken to extremes, even optimism, can lose its way. The same is true with cultural signifiers, the artists seem to say. When a style or image is repeated and divorced from its context, it begins to supercede that context, becoming dangerously unhinged from meaning.

Nightmare City, "All that Is Solid Melts Into Air," 2010 (still), multimedia. Courtesy the artists.

In Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde, the artists attempt to reunite hippie stylization with its cultural and geographic origins. They visit the sites of the ’60s, dressed in the appropriate garb. But when they arrive, nothing greets them. Their blank expressions convey the contemporary obsolescence of these sites; something interesting happened there once, but it isn’t happening now. Such a bland reception suggests there’s nothing to reclaim. The conclusion seems to be that in the 2000s, hippie imagery is merely a distant reference to the idea of the ideals of an earlier period; none of those actual ideals come through in the translation.

In the video installations, the artists’ images are obscured, color bars pulsate across the screen, faces fade in and out. The erosion of the digital image coincides with the deteriorating significance of the artists’ costumes and wands, whose coherency appears equally malleable and unstable. Unrooted from their origins, images are broken down and rearranged in new configurations; the new message is undetermined.

In my next blog post, I talk to the artists about obsolescence, breaking into Altamont, and the performance component of Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde, which took place September 24, 2010, at Queen’s Nails Projects, in San Francisco.