Jan-Henri Booyens is a South African artist based in Pretoria, South Africa. Jan holds a BFA in painting from the Durban Institute of Technology, in KwaZulu Natal. Since 2000, he has widely exhibited nationally as well as internationally. His work may be found at numerous collections but the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art in Paris is the one that stands out. He is currently represented by WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery in Cape Town and he is a member of the visual art collective, Avant Car Guard.

I am presenting Jan today because his work reflects the “sensation,” as he put it, of being a South African. His textures, pallet, forms, and chaos are there to serve the edginess of a reality he naturally discusses in the interview later on. His works read as the artist’s very signature, as a fingerprint — a generous portion of his visual intake is mirrored on his surfaces and I recognize him and his world in paint clearer than by anyone else among his generation of artists. Jan’s work has myriad layers, yet the one that conceptually excites me the most is his take on Modernism and his guts to experiment with and stretch this dogma as if it’s gum between his fingertips. It takes intelligence and informed decisions to initiate a dialogue with a tradition from the past and further successfully produce contemporary paintings today by using a supposedly exhausted vernacular.

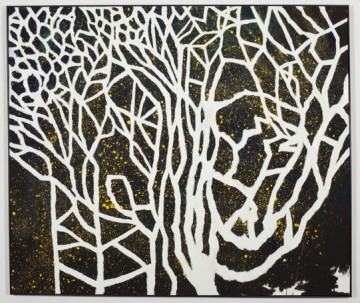

The minute he held up Stoned at the depot of his gallery at the Johannesburg Art Fair last April, I stood there instinctively connecting the dots. Images and texts of Abstract Expressionist painting were flashing before my eyes – it was mentally a cross-art history puzzle. All the information was there, all the clues are still right there; thus, I stand by his side when he wishes he could respond by saying “you figure it out!” every time he’s being asked about the content of his work.

Jan speaks directly to a specialized audience — his work is developing rapidly and with this body of work, he is significantly contributing to the evolution of South Africa painting. It is always a pleasure to present a fellow Durban Institute of Technology alumnus. Please read on…

Georgia Kotretsos: What does it mean to be a contemporary artist/painter in South Africa right now? What kind of voice do artists have and why have you chosen to have two — one as a painter with an independent practice and one as a member of Avant Car Guard?

Jan Henri Booyens: Well it is a cutthroat business out there. Literarily I saw an artist stab a gallerist in the throat one time.

Jokes aside, I’m working in an ambiguous space — between a history of South African art known for its political undertones and that of South African and African abstraction that is rich in mysticism, ritual, and an emotive understanding of the world.

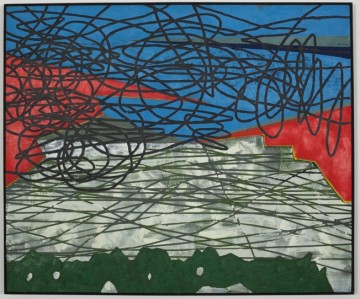

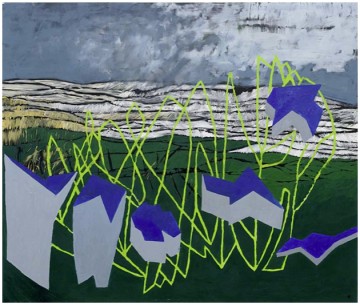

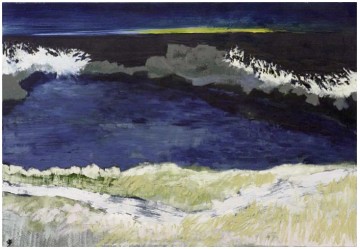

Being African is not an understanding but rather a sensation. South Africa is a volatile space; I get exposed to so much violence, chaos and fear on a day-to-day basis, yet it remains secondary to how beautiful this country/place is. Beautiful is such a weak word for the feeling I’m trying to articulate. What I’m getting at is that natural beauty, nature, land and place are the main themes in my work.

Nature is violent, yet peaceful. Nature is chaos, yet mathematically ordered. These ambiguities, polarities perhaps, also exist in me and in my work. They inform my language. I wouldn’t be able to be an artist in any other place. The world I live in, the world as I see it, is quite messy and chaotic.

The works I make are the result of applying my logic and life experience to the canvas or whatever else is in front of me. That’s my work. It is what it is for better or for worse. Being a contemporary artist/painter in South Africa right now can mean a lot of things but I can only talk for myself. I care about making paintings and I do what comes naturally. I also do drawings, video, photography, printmaking, and installation work.

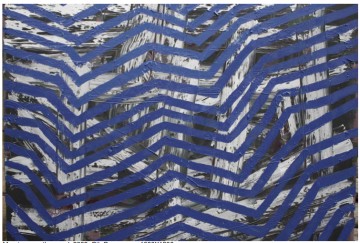

Color and shapes are my alphabet. I can spend hours mixing hues. I want the paint to jump from its surface even if the painting is devoid of bright color. The only color I use directly from the tube is white. I use a lot of white in my paintings to erase, deny, or hide the information of the work.

I must admit that I find myself in a bit of a predicament. One of the reasons I created this abstract language is that I did not want to tell the viewer what he or she should read. I grew tired of South African art dictating the message to viewers. But I still wanted to tell my story without the viewer knowing what the story is. I want the viewer to create her or his own story and relationship with the work. Now, more and more journalists or students writing theses ask me: “So what is the work about? What is the message? What is the concept? What is the meaning?”

Jan-Henri Booyens, "Tectonic" solo exhibition at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa, 2010

All I want to say is: “fuck you, you figure it out.” But that doesn’t seem to work. It seems that if you want to make it as an artist in South Africa or elsewhere, you have to force-feed the audience with a golden information spoon and kiss a lot of ASS. When you don’t want to play the game in the way that everybody expects you to, in the way that they feel they also have to, then you tend to get pigeon-holed as either stupid, arrogant, or lazy. I don’t mind being called any of those things right now.

Collectors in South Africa rarely think for themselves and they need a reason and meaning attached like a little tail to their wallets; otherwise they don’t invest in you. SA contemporary art remains under-valued and under-collected internationally. Locally, it suffers from being subject to a very limited buying market. Historically, SA contemporary art has never performed well because the work has always been so far behind that of Europe or America. It is only now that we are beginning to close the gap and still most SA art remains peripheral.

I’m sorry if I’m starting to sound a bit bitter. It could be that my previous painting show in Cape Town in April did not sell, even though it got an amazing review by Lloyd Pollak on the popular South African art website, Artthrob.

I have noticed that most of the people that do buy my work are either from Europe or the US. This could be because there is a history and greater appreciation, understanding, and education in the language of abstract art.

AVANT CAR GUARD also comes naturally. We are three good friend who are all practicing artists. AVANT CAR GUARD just kind of happens when we get together. Working as a group is great. It can get lonely all on your own in your little studio stuck with your own little ideas. Having another place to go to, to spend time with friends, and to work on ideas separate from my solo work is a real blessing. The name AVANT CAR GUARD brings together the term “Avant Garde” with the South African phenomenon of a “car guard.” A car guard is someone who looks after your car while you are parked in public for a nominal fee.

GK: Some would argue that the South African art bubble has already burst — could this be true? I am creatively and personally invested in it for many different reasons, which makes it harder to tell. Yet, out of all the art fairs I’ve visited in 2010, the Johannesburg Art Fair last April — as intimate as it was, and as visually shocking at first due to the enormous out-of-time/out-of-place central installation — it was the fair that added the most names to my list of artists I should to talk to. I’ve seen burst bubbles and they don’t look like that. What are your thoughts on such projections?

JHB: Arguing that the SA art bubble has already “burst” would make anyone look like an idiot. NO! There’s always a bubble somewhere. It’s just a pity that there hasn’t been a bubble in the quality of SA art criticism after Ivor Powell.

GK: Is there a day job that supports your practice? And are there any short-term or long-term creative plans?

JHB: Yes, I am teaching all the grades from grade 8 to 12, but got really pissed off with the Department of Education’s traditionalist, closed-minded views on what is constituted as art education. This included the syllabus and the marking of the final year (grade 12) artworks. So I quit teaching at the end of 2008 to focus on my art for a year. At the beginning of 2010, I started teaching again but this time only for grade 8 and 9. This experience has been great because I taught art and culture in all the disciplines — art, music, dance, and drama. This gave me more freedom to develop fun projects, where the kids could engage and experiment, get their hands dirty and open their minds. One project stands out: I asked the students to take a traditional African folklore, to write a script and then create and perform a shadow puppet play. It was a lot of fun for me and the students. It is a very rewarding job.

I’m not teaching next year because I received funding from the Swiss Arts Council, Prohelvetia, for a three-month studio program in Basel at the iaab-Ateliers. My project is entitled Shifting Land Mass. The premise will be about the instability and fragile nature of the state of our planet. I will be producing large-scale paintings and using whatever medium comes to mind at the time.

If the funds permit I’m planning some short films – a medium that is inspiring me at the moment. As we speak, I’m printing etchings and linocuts for a show at Trent Gallery, also known as Cameo Framers, in Pretoria. The show will be called “Geen Piekniek” which, translated from Afrikaans, “No Picnic”.

GK: Give us a sense of your working space in a few words, please.

JHB: Think of the state of my studio like so: there is not a surface (this includes the two couches, bed, large and small tables, the kitchen/bar counter, and fridge) that is not covered with inked plates, solvents, paint tubes, more ink, newsprint, paper, spray-paint cans, brushes, glass jars, and yet more paper.

Paintings are stacked against the walls, photographic references and books lie on the floor, dirty ashtrays, coffee mugs, empty beer and booze bottles still stand around from Saturday night when I had some friends over. The printing press rests on an old stainless steel butcher’s table, looking like a relic out of the industrial age or a prop in a B-grade horror film. The areas on the cement floor that are exposed are stained with a variety of colored paint drips and splashes. Framed paintings and drawings are nailed to the walls, giving the space some civility. Open boxes and crates with wires, paint tubes, books, and magazines in them spill out of the shelves underneath the kitchen/bar counter. A sad acoustic guitar and broken skateboard lean against cardboard tubes and rolled up sheets of paper.

Lets not forget, I’m also here………………………………. making pictures.

And, that’s a wrap!