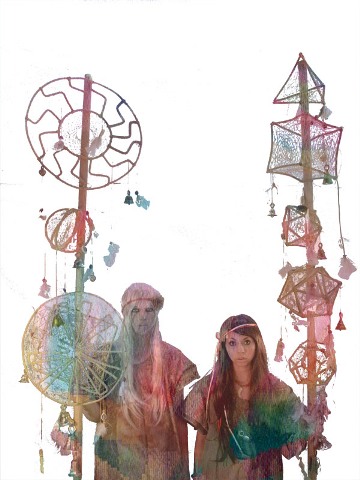

Nightmare City, "Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde," 2010, multimedia. Courtesy the artists.

“It is hard to find California now, unsettling to wonder how much of it was merely imagined or improvised; melancholy to realize how much of anyone’s memory is no true memory at all but only the traces of someone else’s memory …”

―Joan Didion, “Notes from a Native Daughter” (1965)

“The past is not always a burden or a sacred ground. Sometimes it’s just a fun place to shop.”

―Sasha Frere-Jones, in the New Yorker, Nov. 8, 2010, describing the bands Black Angels and Black Mountain.

Working together as Nightmare City, Carol Anne McChrystal and Keturah Cummings make video-based work in which the medium’s disorienting and outdated aesthetic mirrors the unstable meaning of the content itself. For their recent project, Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde, the duo traveled to hot spots of 1960s California counterculture. Dressed in exaggerated hippie clothing, they attempted to reunite those signifiers with their origins. Once there, they were greeted by empty landscapes whose barrenness suggests a lack of meaning underlying such aesthetics, typifying an elusiveness that underlies much of California culture and history.

Here I talk to the artists about the inspiration for their recent project and their performance of California-themed songs at Queen’s Nails Projects in September 2010.

Victoria Gannon: What sorts of things inspired Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde?

Carol Anne McChrystal: We came up with the first inkling of that project when we were at an Indian Jewelry concert.

Keturah Cummings: They’re a noise band based in Houston. It was a whole slew of bands, primarily out of L.A., like Pocahaunted and the Psychic Ills. The music is droney, but very hip, and they were definitely using hippie aesthetics and vague pan-ethnic references.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cgm9XdRZfAY]

VG: Just the name, Indian Jewelry, is very pan–Native American.

KC: But I loved the music, we all did, and I guess that conflict spurred the interest.

CM: In the past couple years, there’s been a general hipness, a back-to-the-land sort of style.

VG: What do you see the style as? Headbands and moccasins?

KC: Yeah, and it’s cropping up in really weird, dissonant ways that aren’t connected to where the imagery originally came from.

CM: So we had this interest and then we put it aside. Then a series of songs came into our daily routine.

KC: We got hooked on Dreams, by Fleetwood Mac.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KCc7MRfdB-8]

CM: We got Mac-attacked, big time. We were talking about doing a cover of Dreams.

KC: We were doing a lot of research on the counterculture era in California and trying to flesh out our responses to this imagery.

CM: We did a lot of research into cults, and on the relationship between hippies and transcendentalists. We saw that the 1960s were a reiteration to begin with, looking back to the transcendentalists of the early to mid 1800s, like Emerson and Whitman. The 1960s sentiment was already a reiteration.

The Manson Family, 1970. Photo courtesy Last.fm.com

I was particularly interested in the Manson Family because Charles Manson posited his identity as a hippie-guru guy, and he brought his followers back to the land and had them Dumpster diving. That cult was most fascinating to me.

VG: Right, when does this positive, idealistic thing cross over into being something really destructive and cult-like?

CM: Sometimes the whole hippie migration to San Francisco is framed in terms of the dynamic of a positive thing becoming destructive.

VG: From what I know of the period, Altamont (the concert in 1969 at which four people died) was considered to be the end of the hippie era, because that’s when things became really dark. After doing some of that research, how did the project begin to form?

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dt0ipUCfdlU]

KC: Eventually we saw connections. It became clear we wanted to do a performance, to inhabit the space those noise bands, like Pocahaunted, occupy, and go back to the initial trigger. We saw this poetic connection between the songs “A Home Is Not a Motel,” by Love; “Hotel California,” by the Eagles; “California Dreamin’,” by the Mamas and the Papas; and “Dreams,” by Fleetwood Mac.

We also saw a connection with Fleetwood Mac, who started as this big communal group, but they eventually descended into in-fighting, affairs, drug addiction, and lawsuits. They were suing each other all the time. We thought that was a good summation of those points we were interested in.

CM: At that point, it just made sense to perform the songs at the sites. We were doing all this research, and I know where these places are; I’ve been there, or I know exactly how to get there.

Nightmare City, "Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde," multimedia, 2010. Courtesy the artists.

VG: Did you feel anything when you went to those sites (People’s Park, Golden Gate Park, Altamont Speedway, and Monterey County Fairgrounds)?

KC: Mostly just nervousness about getting in trouble.

CM: Every time we went for a shoot, we went at 5 o’clock in the morning to avoid people. There was some sneaking into places, like Altamont, which is locked up.

KC: We filmed in front of Altamont’s locked-up gateway, and we went to the soccer fields in Golden Gate Park, where the Human Be-in was, and we went to the Monterey Fairgrounds in front of the stage that the musicians played on at the Monterey Pop Festival. In People’s Park, we stood on the stage.

VG: Did you have any interactions?

Dumpsters at People's Park, November 2010. Photo by author.

KC: At People’s Park, this guy approached us and asked what we were doing our video about. We said, “Hippies.” And he was like, “I can tell you about hippies.”

CM: We were wearing our daishikis. (laughing)

KC: I guess he had lived in People’s Park since the ’60s.

CM: He kept us there for forty minutes telling us how to rip off people with fake drugs.

KC: They would make weed out of tea and wood glue and then sell it to the college students. He said he could make five grand ripping kids off …

CM: That was the only time we had any interaction with anyone. Every other spot, there was nobody anywhere.

VG: It’s really interesting to see the way that radical history is treated on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. It’s really packaged and presented as the street’s identity, even though it’s in the past.

Detail from mural at Telegraph and Dwight Avenues depicting the student protests of the 1960s. Photograph by author.

KC: I work in Berkeley, and I was watching the documentary Berkeley in the Sixties, and it blew my mind. I can’t imagine anything like that happening there, with the college students I see now. Even with the recent protests about the tuition, arrests were made, sit-ins were happening, but it was so much less of a conflict. When I saw those street corners in the documentary, with the helicopters coming in, and people barfing from the tear gas … Now I look at the American Apparel there on that corner, and I can’t believe it’s the same spot.

VG: When I was a kid, I loved going to the Telegraph Avenue, and I went to high school a few blocks away. Even during the ’90s, it felt less commercialized than it is now. Sometime during the ’90s, the homeless people got really mean, and became more street punkish rather than hippieish. But people flock to the area because of its history, and I wonder how much of it is still there. Do the ideals that the place supposedly represents even exist there?

KC: I used to really be into zines, and I read Cometbus a lot, and I had a really different idea of that area reading his descriptions of it.

VG: Even twenty years ago, it felt like the spirit of those protests and that movement was somehow still lingering, whereas now it feels like it’s died, but people are still looking for it.

So you did the four videos, one at each site, and then performed at Queen’s Nails Projects? Were you nervous?

CM: I feel like the performance was more accessible to me because we were being these characters in this hip noise band, putting on these weird, not quite right, muted hippie costumes.

Nightmare City, "Nightmare City Copy Lake The Horde," mixed media, 2010. Courtesy the artists.

KC: It was a caricature.

VG: I liked those big things you were holding, those wands whose tops were drooping.

CM: They were our pan-ethnic devices! (Laughing)

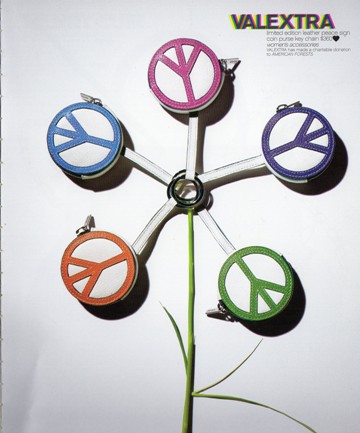

KC: I think the visual aesthetics were definitely more important (than the music). I see those visual aesthetics in the mall, at Urban Outfitters.

VG: I see it everywhere. How many times can you draw a triangle and think it’s profound? Maybe not even once. (laughing)

CM: Are you saying our triangle wasn’t profound? (laughing)

VG: There’s definitely this embrace of mysticism, but without any actually articulated beliefs.

"Have a Hippie Holiday," Barneys winter 2008 catalog. From the collection of Carol Anne McChrystal.

CM: Because it’s cool. It’s like another cycle of its being cool again. It’s like owls are cool. Crystals come around every three or four years.

VG: Horizontal headbands. I don’t know if you wear those―it’s fine if you do―but they drive me nuts. I will never wear one―I have vowed.

Joan Didion writes a lot about California, its doomed and elusive qualities. In 1967, she wrote this essay called “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” in which she goes to the Haight looking for hippies and she finds this emptiness. She has this quote from an unnamed psychiatrist who’s talking about what’s happening. He says:

“It’s a social movement, quintessentially romantic, the kind that recurs in times of real social crisis. The themes are always the same. A return to innocence. The invocation of an earlier authority and control. The mysteries of the blood. An itch for the transcendental, for purification.”

Do you guys think that applies to now? Do you think there’s a correlation between the resurgence of this sensibility and the fact that the economy is collapsing and we’re at war?

CM: There totally is. It’s the signs of resistance and rebellion; it’s a release valve for tension. That’s why there’s a war going on for so long because the resistance movements only happen as a semblance of a resistance movement. The images get layered on top of inaction. It’s like the J.Crew catalog that’s military themed. Or the Barney’s holiday catalog that’s hippie themed. That’s how those sorts of references happen now. You can just buy it and put it on.

"Have a Hippie Holiday," Barneys winter 2008 catalog. From the collection of Carol Anne McChrystal.

VG: Do you think the media you use has a particular ability to deal with these themes?

KC: The media is referencing nostalgia, especially the switch from analogue signals to digital. Now tube televisions are gone; when we were kids, the glass of the TV was a little bit domed, but now that’s obsolete, and nobody’s going to see that image again.

For me, things like that within media are interesting; these same images can be replayed, but the way in which they’re played is different. I think that’s a good thing to play with.

VG: Were there things you did during the performances and when creating the videos to communicate these ideas?

KC: We were trying to represent how cultural repetition can strip things of their power and vitality.

VG: It’s so true, we see the afterlife of things. I was amazed when I watched Berkeley in the Sixties to see that there really was a heart to the movement at one point.

KC: The history of People’s Park is mind-blowing and inspiring.

VG: In the performancc at Queen’s Nails Projects, why did you sing those songs in that way? You start off super, super slow, then by the last one you’re singing at a normal speed.

CM: There’s a different style for each one; we were sort of using a strategy of genre hopping. Copy Lake did the music for us, and we rehearsed with Copy Lake, and he took inspiration from different types of popular music right now.

KC: The first song, “A Motel Is Not a Home,” was cold wave-ish, which is this resurgence of keyboard goth that’s happening right now; “Hotel California” was drone; and “California Dreamin’” was a reiteration of grunge and garage rock, and then “Dreams” was our mini pop song.

VG: Do you feel like you’re done working with these themes? Or do you feel like there’s more?

CM: We’ve been talking about doing one more performance, possibly at the ranch where the Manson Family camped out. We might go there in the middle of the night and have a concert there.

There’s so much within the project itself, even in the footage that we got at the sites. The videos were really manipulated, with a lot of effects. I’m interested to see what they’re like unfiltered. I think there’s some potency in being able to pull out the locations more. If we combined that with the Spalding Ranch thing—there’s something there.

VG: It seems like you’re drawn to that dark moment when things go from being blissful to being dark.

KC: It’s been pointed out to us that we work with various forms of nostalgia.

Screenshot, NightmareCity.org.

CM: A lot of our work deals with inhabiting different modes of producing meaning.

VG: Like your website … I went to it, and at first it seemed manageable, and then I got really overwhelmed.

CM: Geocities vacation! I’m surprised it didn’t crash your browser! (laughing)

We deal with nostalgia in terms of obsolescence, more precisely. It’s in all of our work. The last project we did was a TV show about TV shows from another time.

VG: What is it about obsolescence?

CM: It’s the failure of possibility. New technologies come out to explain some form of knowledge or some way of understanding, hoping to improve our lives. Then something new comes out, and that previous model doesn’t work anymore. That’s the dynamic we’re always approaching in our work. Where’s the place where the promise was, and where’s the place where the promise failed, and what happens in that loosey-goosey space?