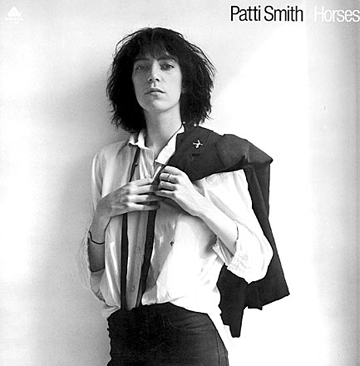

Examples of the influence of music on art are as iconic as they are profuse: Jackson Pollack madly swirling paint around him as Dizzy Gillespie blares on the hi-fi; Andy Warhol’s cover design of the denim-clad male crotch for the Rolling Stones’ album, Sticky Fingers; Robert Mapplethorpe‘s portrait of Patti Smith for the cover of Horses; Jean-Michel Basquiat‘s stint as a punk rocker while playing in Gray; Mike Kelley‘s early involvement in the Detroit-based noise project Destroy All Monsters; Robert Rauschenberg taking inspiration from John Cage’s musical interest in chance by creating bodies of work such as his White Paintings and the Combines.

These works, performances, relationships, and interactions all represent instances where the boundaries between music and visual art have bent and blurred, where sonic experiences have shaped artistic practice and visual expression. In these cases, music — whether created while playing in bands, or consumed while attending live performances or listening to records — acts as a vital social outlet that interrupts the isolation of studio practice. It becomes a productive distraction that ameliorates the intense focus demanded by creative productivity, or an alternative creative outlet that encourages new ways of working out questions about representation and artistic production. In all of these uses, music functions as a sort of fertilizer, absorbed by artists and incorporated into their work in the same way the plants soak up enriching nitrates.

Music also served as an essential model for early Modernists in both Europe and the United States who sought to break free from the pictorial constraints of recognizable form and subject matter. Wassily Kandinsky, whose “Compositions” (a term he took from musical practice) pioneered new uses of line and color, relied heavily on language and concepts taken from music. Early in his career, he wrote, “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” This concept, that art should evoke “vibrations in the soul,” helped visual artists justify experiments with nontraditional color combinations that would produce new methods of representation. Similarly, micro-movements within Modernism such as Orphism (exemplified in the work of Sonia and Robert Delaunay) and Synchromism endeavored to imitate sound tonalities with color, replicating within the field of the canvas the tonal structures and relationships utilized in musical compositions. Georgia O’Keefe was strongly influenced in the early years of her career by the theories of Arthur Wesley Dow, who encouraged artists to abandon representational subjects in favor of reducing painting to its basic elements to pursue a kind of musical harmony. Though the theories that initially inspired artists such as Kandinsky, O’Keefe, and the Delaunays quickly exhausted their usefulness, these ideas were nonetheless widely circulated and deeply influential for early twentieth century artists, and their legacy — in the form of the works they inspired — remains with us today.

Unless a piece is part of one of these sub-genres of Modernism, or the artist makes explicit the influence of music in his or her work, generally viewers are not prompted to consider music as a factor in art. For scholars, questions about an artist’s musical taste, relationships with musicians, or fandom have not generally been regarded as serious topics for investigation. However, as art criticism and historiography continue to move beyond the “isolated genius” model of artistic production to acknowledge the importance of socio-cultural context in the creative process, questions about the relationship of art to music are taking on greater significance. Additionally, as the work of cultural theorists — such as semiotician Roland Barthes — has gained credence within the academy, disciplinary boundaries that often discouraged scholars from studying music and art on equal footing have given way to studies that consider the specific social and political significance of particular modes of representation, whether visual or aural. As a result of these intellectual shifts, new lines of inquiry are opened and new objects of analysis are made available, as evidenced in MoMA’s upcoming exhibition Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914, and in exhibits this past fall at the Steven Kasher and Loretta Howard galleries, which examined the artistic legacy of the storied bar and musical venue Max’s Kansas City. Good news for anyone looking for art exhibitions that give music the intellectual consideration it deserves, by doing more than just blaring it over the sound system during openings or using it between segments of audio tours.

Elizabeth Wolfson is a freelance arts writer currently based in the central Anatolian region of Turkey.