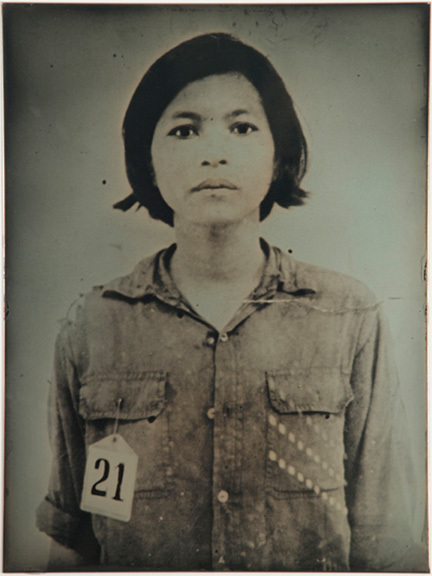

Binh Danh, “Ghost of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #2,” 2008. Daguerreotype, 11 3/8 x 9 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist

Binh Danh: In the Eclipse of Angkor at the North Carolina Museum of Art reveals Vietnamese born artist Binh Danh’s search to imbue photographs with meaning not only through subject matter but also through process. The subject of Danh’s latest photographic series, The Eclipse of Angkor, is the anonymous victims of genocide in Southeast Asia. Danh re-photographs the portraits of unidentified victims of the Khmer Rouge who were executed in Cambodia’s notorious Tuol Sleng prison, which, along with the Killing Fields, became synonymous with the Khmer Rouge’s brutal reign of terror. Danh employs two photographic techniques to produce his images—the daguerreotype process and a unique chlorophyll method invented by the artist.

The photographs in In The Eclipse of Angkor stem from Danh’s 2008 trip to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Choeung Ek, the site of the Killing Fields and Angkor Wat, Cambodia’s celebrated twelfth-century temple complex. During the trip Danh was struck by the meticulous photographic documentation on the part of the leaders of the Khmer Rouge of the estimated 30,000 Vietnamese and Cambodians who were imprisoned and died in Tuol Sleng prison between 1975 and 1979. Danh, who was born in Vietnam in 1977 to a Cambodian father and Vietnamese mother, has no personal memory of the Vietnam War or Cambodian genocide. His family fled to the United States when he was only two years old, and he did not return to the region again until 1999. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Danh’s artwork aims to restore and reclaim memories, identities and histories—both personal and collective— in an effort to come to terms with a dark period in Cambodian history.

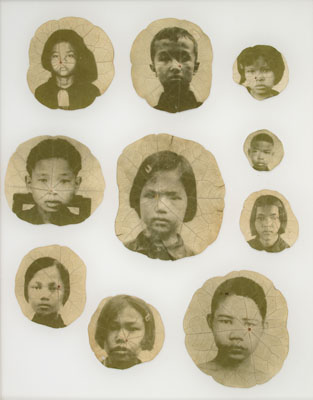

Binh Danh, “Memories of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #1,” 2008. Chlorophyll print on nasturtium and resin, 12 x 10 inches. Courtesy the artist.

The first photographic process Danh uses to make his prints of the Khmer Rouge era images for his In The Eclipse of Angkor series is a chlorophyll process, which he invented. The process involves placing a photographic negative of one of the re-photographed images directly onto the surface of a living leaf, securing both leaf and negative under glass, and exposing then them to sunlight for days or weeks at a time. Through the natural process of photosynthesis, the image from the negative becomes printed into the leaf’s light-sensitive surface, incised directly into the leaf’s very structure. Danh then preserves the resulting image—which he refers to as a “chlorophyll print”—by coating it in resin.

The second method Danh employs to make his images is the daguerreotype process, which dates back to the 1830s and involves a labor- and time-intensive process wherein a highly polished, light sensitized copper plate is carefully exposed to light, after which the latent image is developed with fumes from heated mercury. The resulting image was of such stunning clarity and detail that the daguerreotype was often referred to as a “mirror with a memory.” These metal images proved immensely popular in the nineteenth century, but they also had their shortcomings, as the process was cumbersome and complex, required long exposure times, and the images were not reproducible since directly printing onto metal plates meant that there was no negative.

Together, the images reproduced on Danh’s chlorophyll prints and daguerreotypes of these Khmer Rouge-era photographs form a haunting index of systematic genocide. But Danh’s distinctive photographic processes and prints also transform the images into something more. Incised on a shimmering plate of metal or into a delicate leaf, each portrait becomes part relic and part photograph, and is invested with a powerful presence. It is no coincidence that both of the photographic processes Danh employs are time-consuming, complex methods that generate unique prints. By re-photographing images of anonymous victims of mass genocide using photographic processes that generate unreproducible images of extraordinary detail, Danh’s chlorophyll prints and daguerreotype plates restore a sense of individuality and intimacy to the victims depicted in the Khmer Rouge portraits. In addition, the extraordinary surfaces of Danh’s prints, as indexes of the time and great care required to produce them, invest the portraits with a significance and uniqueness that offsets the detached, bureaucratic objectivity of the original photographs.

Danh’s re-photographing of these portraits also hints at a broader reclamation project on the part of the artist. In particular, Danh’s appropriation of the daguerreotype process—whose French origins allude to Vietnam and Cambodia’s colonial past—bestows upon his images of Vietnamese and Cambodian victims a symbolic significance that exceeds the individual portraits depicted, and suggests that the goal of this project is not just the restoration of individual identities but of collective identity as well. This broader aim is also suggested in the title of Danh’s photographic series itself, The Eclipse of Angkor. After all, the notion of Angkor Wat, the twelfth-century Khmer temple that stands as a symbol of a past glory and the apex of ancient Cambodian civilization and culture, being plunged into shadow speaks to a need to reclaim a collective history and identity that has been eclipsed by the region’s complicated and traumatic recent history. In this sense, Danh’s daguerreotypes and chlorophyll prints can be thought of not so much as “mirrors with memories,” but as mirrors in the service of recovering memories. It is an ambitious task, but one that commences in earnest with Danh’s unique process of restoring a sense of dignity and presence to the portraits of individuals that have been lost to the Killing Fields and prisons in one of Cambodia’s darkest moments.

Binh Danh: In the Eclipse of Angkor is on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art until January 30, 2011