Pamela Johnson, "Ice Cream I," 2009. Oil on canvas, 54 x 34 in. Courtesy the artist.

After exhibiting at The Artist Project in 2008, Pamela Johnson’s American Still Life series began getting attention. Pepperdine University’s Weisman Museum of Art, Adler & Co. Gallery, and the San Francisco Fine Art Fair, all in Johnson’s native California, exhibited the junk food paintings, as well as Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, PA, All Rise Gallery and the Union League Club in Chicago, among others.

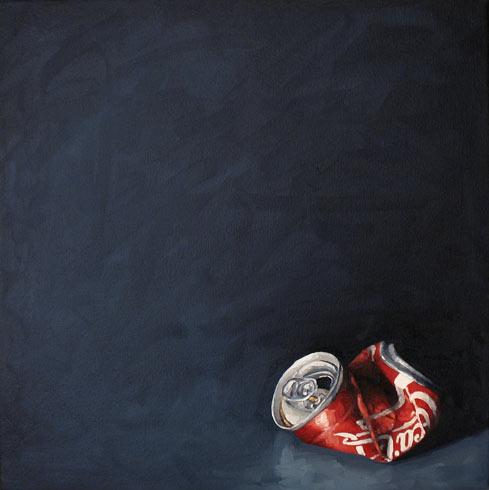

Magazines including Juxtapoz, Creative Quarterly, Poets and Artists, and Chicago Home & Garden ran stories, interviews, and images. In November of 2009, Johnson was the recipient of the Alice & Arthur Baer Award as part of the 33rd Annual Beverly Art Competition in Chicago. Her art was being acquired by institutions and traveling the country, and a second wave of the American Still Life series was unveiled which used the same gorgeous technique and compositional strength to focus on the aftermath of consumption as set out in series one. First what we eat, then the garbage amassed when we’re momentarily satiated. Discarded M&M wrappers and crushed Coke cans, Starbucks cups and twisted packaging, half empty bottles of syrup and jars of strawberry jelly, crumpled bags of Doritos and boxes of Frosted Flakes; “empty wrappers forgotten and abandoned in a world of nothingness question the sustainability of our excesses,” in Johnson’s words.

Pamela Johnson, "Coke," 2009. Oil on canvas, 15 x 15 in. Courtesy the artist.

Pamela Johnson, "Cool Ranch," 2009. Oil on canvas, 20 x 20 in. Courtesy the artist.

Disposable plastic and paper that will linger on sidewalks, in gutters and landfills, and swirl in oceans for longer than anyone can guess. Though series two is less confrontational than the big in-your-face junk food canvasses, their poetic quiet sharpens itself against our habits more subtly than the larger pieces; Johnson gets you from both directions. The trash we create and ignore is yet another kind of evidence in the broader argument against mindless indulgence.

I found it somewhat ironic when considering art as evidentiary information against our less noble attributes that, in June of this year, I got an email from Johnson regarding Lyon and Lyon Fine Art, a New Orleans gallery she had sent several paintings to in 2008.

Not sure if I told you already, but the gallery went out of business over a year ago and, well, decided to keep everyone’s work. The attorney general is actually putting together a case against the owners of the gallery.

Johnson estimates that there about 30 artists still seeking the return of unsold work, as well as payment for work sold while hanging in the gallery.

Johnson told me that the owners of the former Lyon and Lyon Fine Art, Ron and Taylor Lyon, have since opened a new gallery down the street from their last venture called Graphite Gallery. After months of slow communication with authorities in New Orleans, Johnson says not much has been happening and that she’s relying on karma to settle the score at this point.

On the 2nd of December I emailed Graphite Gallery to see if anyone there would be willing to talk to me, and, not surprisingly, I didn’t get a response. A week later I called and asked to speak with either of the Lyons, and was told by Taylor Lyon that he had only been an employee at Lyon & Lyon Fine Art and that he had no way to get in touch with Ron Lyon, his father. Taylor also said, after giving me the name of one of his partners at Graphite – a lawyer – that Ron Lyon wasn’t associated with Graphite Gallery in any way.

Shortly after I spoke with Taylor Lyon, his lawyer and co-owner of Graphite, Andrew Allen, emailed me to reiterate that Taylor “never had any ownership interest whatsoever in Lyon & Lyon,” and that I was to “direct any future correspondence concerning Taylor Lyon” to Allen’s attention.” Which I promptly did. As of the date of publication for this piece, Mr. Allen has not answered any of my questions regarding Taylor Lyon.

Pamela Johnson, "Bunny," 2010. Oil on canvas, 28 x 28 in. Courtesy the artist.

I followed up with Johnson and she told me that when she originally met Taylor at The Artist Project, he claimed that he owned Lyon & Lyon with his father, and that after the gallery closed and a case was being built, Taylor began referring to himself as just an employee.

Lyon & Lyon Fine Art sent out a mass email in May of 2009 to announce that they were closing their doors. Johnson first heard about the closing, however, from other artists exhibiting there. She told me that Ron Lyon kept promising to ship her work back, but that after a couple of months, he stopped returning her calls.

Maurice Maranto, investigator in the Louisiana Department of Justice, told me that he had compiled the original list of victims and damages in the case, but that ultimately responsibility fell under the jurisdiction of the District Attorney, Orleans Parrish. After contacting both the Attorney General’s and the D.A.’s office, I was told that the case is open and underway.

I was shocked to learn that Johnson’s work had been stolen. Typically when one hears about art theft, it’s some priceless work by one of the widely known masters, and people almost understand the act. A Picasso is worth a lot of damn money. I place a high value on Johnson’s work as well. Art that speaks such direct truths belong to grand collections just as much as they belong to each of us on the street. When we allow art to confront our behavior, we have an opportunity to gain deeper understanding of that behavior, and junk food and garbage have something to tell us about who and where we are in the world. Such messages must be spread, not stolen from us. We allow enough to be stolen already. If we can pick up a bit of our own refuse and see what it obscures, we may learn that what we consume on a daily basis is nothing more than a distraction from the bigger picture, and we may then be more capable of connecting pieces of ourselves to each other. Ultimately, that connection is what I look for in art and artists, and what I’ve found in Pamela Johnson and her waffles and cupcakes and crushed cans. Those images contribute to my awareness of who I am and offer insight as to who I might like to be.

Pamela Johnson, "Starbucks," 2008. Oil on canvas, 18 x 18 in. Courtesy the artist.