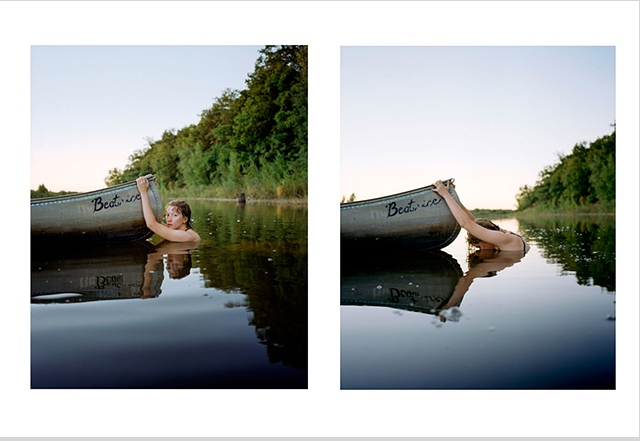

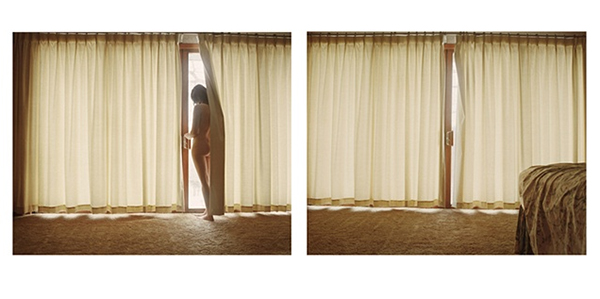

While always being aware of her work, Melanie Schiff snapped into focus shortly after I first heard about Ox-bow, the School of the Art Insitute’s residency program in Saugatuck, Michigan. Friends came back from a summer there looking a little wild. Melanie’s work–color-rich photographs of youths blending into trees, whiskey bottles glinting like a candle in a bath of morning sun–offers a portrait, not just of Ox-bow, but of a feral, post-adolescent youth. It would be inaccurate to distill her prolific energy into one characterization; her work is lush, well-composed and ever-sensitive to silky light. Those aesthetic concerns transcend specific subjects. In addition to empty skate-park landscapes and attic rooms, she has made self-portraits with bong hits, another with raspberry-nipples, another involves spewing water in the sun (always reminds me of Tony Tasset), or the one above, where she reclines in a sea of empty bottles glinting like a deteriorated Jeff Wall interior: these gestures position her-self-as-artist, approximately tied to a flanking landscape of, often exclusive, culture. Whether holding the Neil Young album before her head, or photographing a motel room once occupied by Kurt Cobain, her presence adds an idiosyncratic awareness to these cultural referents. In an effort to explore that affect, I asked her a series of questions, primarily about the camera and its gaze. This is one interview in a series of many that explores the self on either side of the camera, while thinking through the respective position of the artist.

Caroline Picard: What happens to your perspective when you look through the camera?

Melanie Schiff: I think a lot of it is just practice. When I look through a camera, everything exists on a plane; now start to try and organize the visual space, which is a lot easier said than done. It can be fairly frustrating — many times things don’t translate right away and it takes a lot of problem solving. I think there are perspectives that I find pleasurable that I also feel have a universal appeal. Art history is an archive of compositions, and you end up referencing them consciously or not. I feel like when I’m trying to compose a photograph, that there’s almost a sweet spot in the frame, and it’s just about trying to figure out where that is.

CP: Is the camera lens a consistent frame of reference/filter for you?

MS: Yes, but at the same time, the camera still surprises me. While I think I can understand how something will look photographed now, better than let’s say ten years ago, there’s still a sense of wonder when I get my film back. Things fail that I thought would work, and I’m surprised by what images I find compelling.

CP: Does looking through the camera change your experience of yourself?

MS: I’m not sure if it changes my experience of myself, or if I’m someone specifically drawn to camera-based photography because of the person I am. I feel like photography is somewhat of an outsider’s pursuit, even photographers whose main goal is to seem as though they are part of the situation are many times the observer more than the participant. Photography allows you to look without distractions. That kind of experience can be meditative and calming under the best circumstances, which may not always be the case, but worth trying for.

CP: What is the difference, in your mind, between a self-portrait and a portrait?

MS: That’s a hard one, because I think many things that are labeled a self-portrait or portraits are neither. Meaning that just because one photographs a person or oneself does not mean that the image is reflective of that individual. When I use myself in a photograph, I think of myself as a symbol for artist/maker/woman; in many ways it’s the most reductive way to include a human figure. When I started taking photographs of other people, mostly young woman, it was because I really wanted to be a photographer again. I missed being on the other side of the camera, I’m not sure my black and white photographs of young women would fulfill my criteria of a portrait. I think the subjects straddle between being models and individuals.

CP: Can you talk a little about your ability and interest in quoting music icons into your work? I was thinking of that image of you in the woods with the Neil Young album cover, or the swimming pool image with the Joni Mitchell album….I guess I’m interested in how you incorporate yourself into these different histories, somehow?

MS: I haven’t used that iconography in my work for the last few years. While lately they’ve taken on different forms, the more I think about it the more I believe that I still have many of the same concerns. The album covers are about a wanting and desire; I have such an attachment to certain albums and objects that I‘ve felt a need to insert myself into their history. I think all of my references have to do with a love of the subject matter, whatever it may be.

CP: A couple years ago or so, you moved from Chicago to California. Do you feel like the change in environment has influenced your work?

MS: The biggest change for me moving from Chicago to California is the quality of light. Light in Southern California can be harsh, strong, cutting, and even on gray days, there’s a sharpness that feels different than light in the Midwest. It’s still taking me awhile to get used to — initially the sunlight seemed so bothersome that I would only shoot early in the morning. I really like the Los Angeles winters, which I suppose come as no surprise having moved here from Chicago. But what I really like is in the winter when it rains and how it seems the city is not really prepared for how much overgrowth occurs. There’s this terrible smell that took me awhile to figure out, but I realized it is the smell of plants rotting, which also becomes pleasant somehow, because it makes me feel like I live in a wild place, where nothing can be totally controlled.

CP: Do you feel like you have a relationship to an audience?

MS: Certain places interest me because of their history, even if it’s a fictional history, specifically places that have a creative (for lack of a better word) history. It may be somehow connected to being a photographer, there’s always a desire of looking from the outside in, being a privileged observer. I like to think that there’s the same spiritual draw for me and maybe others; to places where artists make work, where songs are written, where trees grow, as there would be to temples and churches for others. Some places have a uniqueness that only exists in moments, which is yet another capability of the camera, to take that moment, or sometimes make that moment, so that it can last forever.

CP: I was wondering if you could talk a little about your newer projects–I was thinking about your skate park images, though perhaps they’re not new….

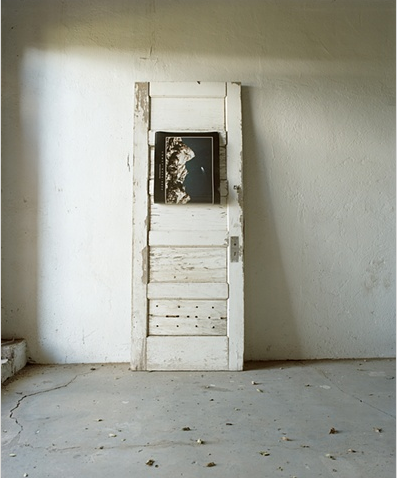

Melanie Schiff, "Hell Room," 2009, Digital C Print, 30.5" x 34"

MS: Actually the skate park piece was made in Chicago, it was kinda prelude to my move, and while I haven’t done pieces with figures in them since moving here, I did shoot a good lot of the mirror and mastodon body of work at this secret skate pipe at the base of Mt. Baldy out where I teach. I love how the place had a strange sense of both past and future — I wanted that work to have a real science fiction feel to it…a bit like Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Looking back, maybe that had do with my feelings regarding the move — California is so different from the Midwest. I think I’m still looking at through a stranger’s eyes.

Pingback: Interviews on Art21 | The Lantern Daily

Pingback: Reader: Jan 5, 2011 | updownacross

Pingback: Art:21 interview with Melanie Schiff « MW Capacity