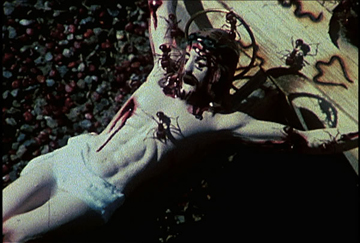

Still from David Wojnarowicz, "A Fire In My Belly" (Film In Progress), 1986-87, Super-8mm film, black and white & color, silent. Courtesy The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York and The Fales Library and Special Collections/ New York University.

The artist-gallery relationship presents a curious contradiction. That is, there is the notion that a gallery representing contemporary artwork has a certain responsibility for promoting challenging and inspiring ideas, whereas, simultaneously existing, and at odds with this general expectation, are calculated changes occurring within gallery rosters and inventory. In the much-affected art market, increased pressure for saleability is directly influencing decisions such as which artists a gallery is willing to represent. While artists are assumed to be chosen by galleries for producing exciting and dynamic work, they are often picked for the purpose of attaining a level of universal accessibility in an effort to generate revenue. Granted, this approach is by no means new — a for-profit arts institution is, naturally, motivated to maintain financial stability. The point of concern, though, is the escalating dominance of efforts towards ensuring saleability overshadowing the gallery’s role of cultivating and encouraging artistic growth within its local arts community.

This impulse for survival is something that all creative fields have become acutely aware of, encouraging shifts towards new (and less costly) forms of marketing and self-promotion, as well as through making “safe” directorial decisions. Now, although such tactical adjustments may indeed provide a positive long-term shift in the way many institutions are managed, it does not excuse them curatorially from denying access to potentially dialectical creators. As much as creative institutions run the risk of causing offense with works that may challenge the sensibilities of a pre-existing client base, there is perhaps even more at stake when they become overly cautious. In addition to reaching out to new members of the art community with more progressive forms of marketing, the work represented ought to reach towards this new-found progressive audience as well.

Museums face similar challenges. The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, in particular, having both received an abundance of attention for recent removals of works from public display, and are under intense scrutiny for issues of censorship. Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery has been criticized for David Wojnarowicz’s video, A Fire In My Belly. The work was opposed by the Catholic League and several members of Congress for a moment showing ants crawling over a crucifix. Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS in 1992, intended for the film to express his experience with the disease and, ironically, to speak out against oppression. Also a victim of censorship was a mural by an Italian street-artist, Blu. The mural, commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art, was an antiwar statement depicting military-style coffins draped with large dollar bills. Upon nearing its completion, it was promptly painted over for the reason, according to the museum, that it was “inappropriate.”

Though the means of sustenance for a museum are different from those of a gallery, that does not discount the reality that their coexistence is mutually influential. Traditionally, it is understood among visual artists that in order to catch the attention of the museums, critics, and collectors, seeking representation from a gallery is the appropriate first step to take in an emerging career. However, many are finding new ways to achieve exposure for their work outside of the gallery-stratum, oftentimes bypassing the galleries altogether on their way to public recognition.

Motivation for artists to seek different mediums of exposure comes from a growing frustration with gallery methodology. The intended reward of an artist-gallery relationship is the intimacy and trust, assuring the artist that the gallery has the necessary expertise to give prominence to the artwork the artist provides. The artist is also, in a sense, trapped within the parameters of the gallery’s influence. Artists can be encouraged to maintain a certain style, or discouraged from experimenting with new ideas. Artists are also frequently under contractual obligation to conduct all sales through the gallery, regardless of whether the space is in physical possession of the work. This relationship, motivated by the desire for producing profitable art, has the capacity to steer the progression of an artist’s oeuvre and potentially limit it.

However, a positive result of institutions failing to accommodate the need for free expression is the catalyst it provides to artists who respond with fresh paradigms. After all, artists are innovators by nature, and they will create new channels through which their work can be accessed when the customary pathways deny them. As far as creative advancement is concerned, it’s clear that catering exclusively to the tastes of potential patrons inhibits an artist from maintaining integrity of artistic vision and, consequently, from producing the kind of work that may ultimately win them the greatest recognition. Having so little support and attention as it is, artistic institutions must recognize that a homogenized, weak output will eventually cause them — and the artists they represent — to become overlooked entirely.

Ashley B. Martin is co-founder of the Cooperative Artists’ Trade, which showcases under-represented artists, musicians, writers, and all others who bamboozle the human senses.