“…We look backward at history and tradition to go forward; we can also look downward to go upward. And withholding judgment may be used as a tool to make later judgment more sensitive. This is a way of learning from everything.” — Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977)

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas, 1966 © Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia

In October 1968, Yale professors Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, along with Steven Izenour, embarked on a study trip with thirteen students. They headed out to the Sunset Strip of L.A. and Route 91, or simply the Strip, of Las Vegas, with the hope of conducting sensorial and experiential architectural research. Since both of their chosen destinations defied reduction down to a singular vision or architectural style, they were the perfect sites for the class’s collaborative research activities and, ultimately, for revealing how architectural design relates to urban planning.

Originally named “Learning from Las Vegas, or form analysis as design research,” by the end of the trip, students had taken to calling the course, “The great proletarian cultural locomotive.” Along with a trip to Disneyland, while in L.A. they went on a studio visit with Ed Ruscha and landed a ride in Howard Hughes’s helicopter.

View of "Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown," Dining Room, Madlener House, Chicago, 2010 © Graham Foundation

A related exhibition, now on view at the Graham Foundation, is entitled Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. It’s a mixture of super-saturated Technicolor photographs, films, slides, and printed ephemera from their trip, some of which were included in their subsequent book, and which viewers can spot in the facsimile page layouts on view, and some of which were left like buried treasure in the Venturi/ Scott Brown Archives.

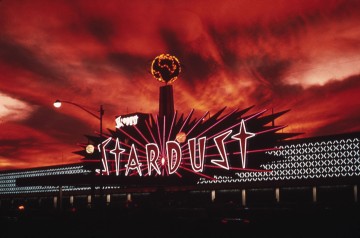

Stardust Hotel and Casino. Las Vegas, 1968 © Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia

The show sprawls across all three floors of the Madlener House, which is itself a work of art. The Gold Coast gem is a mixture of German Classical architecture and Prairie Style ornamentation, replete with plaster cast, coiffered ceiling panels, mahogany molding, and an adjoining yard strewn with architectural remnants.

View of "Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown," Music Room, Madlener House, Chicago, 2010 © Graham Foundation

Peter Fischli, one half of the artistic duo Fischli/Weiss, collaborated on the design of the exhibition, and the salon style cloud cluster of photographs in one of the first rooms of the show is an authentic mimicry of the manic experience of Las Vegas itself. Even the still photographs feel frenetic, as pictures of famous casinos, such as Caesar’s Palace, The Flamingo and Circus Circus, are punctuated by ones of roadside pit stops, root beer stands, parking lots, balconies, and gas stations. All of Las Vegas’s synthetic splendor — writ large across marquees, slapped up on the sides of billboards, and flashing in the neon lights of the city at night — is tempered by more somber behind-the-scenes shots, such as the sobering “sign graveyard.”

Studies of Billboards, Office of Young Electric Sign Company, Las Vegas, 1968 © Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia

Several photographs emphasis the horizontal car culture sprawl of the Strip, and the sequential ticker tape-like series of images that document the cars’ eye-view of Las Vegas are deeply indebted to Ruscha, whose artist’s books such as Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations (1963) and Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) left a lasting impression.

The speed accelerates as viewers ascend to the top floor of the house and take in several of the slide projections and films, some of which were made by mounting a camera to the hood of a car. The scale, speed, and glut of overstimulation that is Las Vegas comes across in a dizzying display of simultaneity.

The group’s experimentation with new technologies was supplemented by a non-traditional approach to the typically static maps, tables, diagrams, and charts of academia, and they, too, manage to capture some of the dynamism of the city. A large format matrix of photographs of each major hotel in one column and the humorous epitaphs students attributed to them in the subsequent rows breathes a savvy wit into even the driest of facts and figures, such as “The Aladdin: Moorish Tudor,” “The Tropicana: Bauhaus Hawaiian,” and “The Stardust: Arte Moderne Hollywood Orgasmic Organic Behind.”

"The Big Duck" shop in the shape of a duck on the highway on Long Island, Flanders, New York, um 1970 © Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia

Several years later, images and ideas collected on their trip would culminate in the seminal text Learning From Las Vegas, written by Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour. A central tenet of the treatise was the “duck vs. the decorated shed.” It summarized everything they had in fact learned from Las Vegas, in that the architecture they viewed on their trip was most commonly manifest as a commercial ad (as in the case of the Duck Hut), or as subsidiary to a commercial ad (in the case of a building whose sole purpose seemed to be supporting the signage it bore). Their radical pedagogy, image creation and collection, and personal archive, as represented by this exhibition, all continue to cast a long shadow over the field of architecture specifically and our understanding of post-modernism in general.

Roman Soldier, Caesars Palace Hotel and Casino, Las Vegas, 1968 © Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia

Las Vegas Studio. Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown is on view at the Madlener House, Graham Foundation, Chicago until February 12, 2011.