Several months ago, even before I set my foot on Catalan ground, I was captivated by a seemingly modest photograph: a chocolate candy in a golden wrapper set on a tip of the kitchen knife, which displayed a fresh bite mark, still dripping with saliva. Its caption read matter-of-factly:

I work 40 hours a week in a Spanish high-class chocolate boutique. While working on October 12, I stole three sheets of 24-karat gold and a Guanaja chocolate bonbon. I covered the chocolate with gold and ate it to celebrate the National Day of Spain.

Instantaneously, the image and the statement conjured much more than Proust’s madeleine could ever have. A simple, indulgent gesture became the present’s revenge on the past and on its own self. There we were, set up to ponder the nationalistic pride of Columbus’s discovery of the Americas and the riches and delicacies with which he gifted the Old Continent (Spain celebrates its national holiday on the anniversary of Columbus’s first landing in the New World). However, a few swift anthropophagic nibbles were about to gnaw this self-esteem away. A young immigrant retail clerk claimed what should have always belonged to her. Her body enacted the rebellion through the most direct means available: consuming the forbidden (yet, justly hers) treat.

This ingenious piece was conceived by a young Peruvian artist living and working in Barcelona, Daniela Ortiz de Zevallos. Even though the Spanish colonial empire was dismantled long time ago, shared linguistic and cultural heritage continue to draw scores of artists from Latin America, who seek to enhance their education or advance their professional careers, to the country. Like many of her compatriots, Ortiz arrived here to continue her art studies at the University of Barcelona (UB). Since her graduation in 2009, she has undoubtedly marked the scene here with her audacious presence, participating in more than a dozen exhibitions in 2010 and sweeping pretty much all the major fellowships and grants available. Her project 97 Housemaids was published with the Art Jove grant and recently, she was awarded the prestigious Guasch Coranty Scholarship for her new project, Service Room.

As Ortiz is orchestrating another transcontinental move, this time to Mexico City (Ortiz will begin her postgraduate studies at SOMA in Mexico City, an experimental education platform co-founded by Teresa Margolles and Yoshúa Okón among others, in just a few weeks’ time), and preparing for three solo shows that are to take place here in Spain in June, we shared a conversation about the origins and influences on her precise, taxing practice and her ambiguous status in Spain that continues to be fodder for her projects.

Daniela Ortiz in collaboration with Xose Quiroga, "Royal Decree 2393/2004," installation detail, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

Dorota Biczel: I don’t think it would be an overstatement to say that you are an artist on the verge of breaking out into an international career. Could you talk about how this current situation came about and why you decided to go to Mexico? I am asking because I know that behind the “glamour” of your international moves, there are some hard realities that are not very apparent and worth exposing.

Daniella Ortiz: I can say I am international, but without an authorization to be. I grew up in Arequipa, in the south of Peru, and at the beginning, I had this typical colonial idea that art did not exist in the periphery, but in cities like New York or Paris. So, first I went to Lima and then I moved to Barcelona, going through an intense process of declassing and – because of economic reasons – putting behind me the idea of artworks as aesthetics objects.

[Within] two weeks, the expectations I had of Barcelona were replaced by a full-time job and a college with outdated teaching methods. At that point, I began learning to understand the wage labor system and operate under the conditions imposed by the Spanish immigration law. After 3 years, not only did I get used to living on those terms, but I also started making projects about them.

Last year, when I was doing research for the project Royal Decree 1393/2004, I got to see what is really happening here. That’s when I decided to evaluate the idea of moving out of Europe, to find other places to do my work. While Europe’s turn to the right is very interesting to experience, it is reaching a point in which foreigners’ freedom is at risk. I decided on Mexico mainly because of its historical relation with Spain and Peru. Also, SOMA seems to be a pretty interesting platform of study, as it puts you in straight direct contact with working artists and curators. Anyways, as we all know, Mexico is not a paradise at the moment, so I guess another set of interests might come up there.

Daniela Ortiz in collaboration with Xose Quiroga, "Royal Decree 2393/2004," installation detail, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

In the end, it may sound glamorous to be an international artist, but the glamor disappears when you function under immigration laws that have been adapted according to the political and economic needs of the moment, when the category and value given to an individual seem to work according to the order of nationality, race, social class, and gender. Inside this order, whether you are an artist or not doesn’t count. Everywhere you find limits preventing you from becoming a body that, by its fluency, feeds the altermodernity Bourriaud proposes. Bodies and signs have been flowing even during the African slave trade, but something that is missing here is: in which category do we flow?

DB: In your recent submission for the Berlin Biennial, you said that you couldn’t associate yourself with any traditionally understood political position: be it the right, the left, or the center. Yet as far as I can recall, your projects were at times accused of being overtly political, “sociology, but not art.” Explain a bit more what you meant and why you feel that way. If traditional politics is not the way, how do we go about managing our social, economic, etc. futures?

DO: Many of the bases of the modern international law are founded on Francisco de Vitoria’s De potestate civili. Interestingly, De Vitoria also wrote Justos Titulos to justify the Spanish presence in the Americas. He is very clear when he refers to the Indians, “with their backwardness, mindlessness” as those who, together with “peasants, disabled,… should be protected.” However, he also exposes [that] Spaniards have the right to freely move through the Americas. If this is where traditional politics, the current royal decrees and the Spanish immigration laws have their roots, we would have to place ourselves in the position of the mindless and disabled to work in this frame.

My interest in social and political issues comes from personal experiences; most people in Barcelona’s art scene have nothing to do with visas or CIE’s (detention camps for illegal immigrants). People hear the government is working on better immigration laws in order to protect them, that the European society worked hard for its welfare and that this has nothing to do with colonialism. I dare to say that from certain social positions, it might not be a good idea to talk about politics or social issues, as it would require assuming a lot of responsibilities and quitting some of the so-called rights.

On the other hand, in Latin America, due to the lack of governments’ involvement, people are forced to make decisions in order to survive; they really need a real political thought. Recent changes, especially in Brazil, where the president comes from [the] guerrilla [movement], and Bolivia, where the president arrived from coca growers’ unions, are very interesting. Both of them have been trained in politics within other structures and with other kinds of priorities, which seems promising.

Daniela Ortiz in collaboration with Xose Quiroga, "Royal Time," documentation, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

DB: Could you describe briefly how your projects develop? What I find really fascinating is that sometimes you take very complicated ideas and encapsulate them in very brief, concise projects (such as N–T or Royal Time), while at other times, in quite the opposite manner, you deal with a lot of research material that translates into works with an almost archival quality (such as 97 Housemaids). You use both tactics very effectively though, and I wanted to know more about the process that takes you from the initial idea/concern to the final proposal or work.

DO: Every time I start a new project, I find myself working with new types of materials and images, which demand different media and a whole new structure. But I do have two lines of methodologies as you observed: one is an immediate reaction, when a situation requires a fast and effective answer. I often use what I have readily available at hand, then realize these projects without a budget.

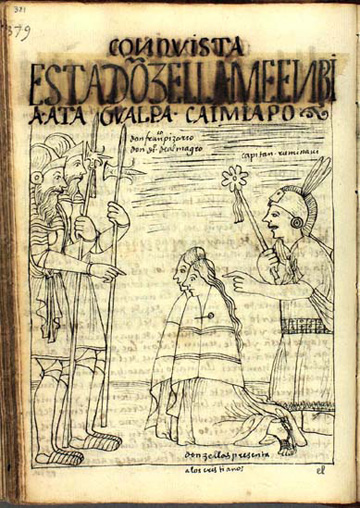

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, illustration from "The First New Chronicle and Good Government. On the History of the World and the Incas up to 1615." Courtesy Daniela Ortiz.

On the other hand, I work researching and putting together archives of different themes. For example, the project of 97 Housemaids derives from the research on Guaman Poma de Ayala. I began to collect contemporary images on the same themes as in the chronicle written and drawn by Guaman Poma, when I got to a drawing in which two donzellas (both appearing in the middle of the picture) are given to Pizarro as maids. I started to look for images with contemporary housemaids, and I ended up finding the first one on a Facebook profile, where the maid was occupying the centre of the image, which worked well in comparison with Guaman Poma’s drawing. However, looking for more pictures, I found out that housemaids always appeared in the background or cropped from the images, basically reflecting the position that they have in the high class Peruvian household where they work and practically live.

DB: We talked previously about young artists in Catalunia and various legacies of Conceptualism you can trace here. First of all, would you consider yourself a heir of the Conceptualists and if so, what does it mean for you, in our day and time? Second of all, what are the dangers of something you called “formalist” Conceptualism, and how can you disassociate yourself from that trend given that on a superficial level, you might be using similar strategies and solutions in your work?

DO: Frankly, I didn’t even know that much of Conceptualism’s history when I started using that logic for my work. When I first came to Barcelona, I saw all the people in my class doing that kind of “logical game,” so I started copying a bit this way of solving problems. In the text written by Marcelo Expósito for 97 Housemaids, he claims that the work I’m developing consist of an update, rather than a repetition or an imitation, of the historical Conceptualist practices of “the South,” which are been recovered now. If my inheritance stems from “the South” or collectives like Grup de Treball in Cataluña, then I’m definitely not in line with the work of many young Catalan artists. It tends to reflect on the artwork itself, its own methodology and own languages, leaving only aesthetic traces of Conceptualism. I do not mean that the contents have to be purely “political,” but I do want to see things that are comprehensive or relevant and not an absolute vacuum. It is important to say that most of the art institutions here are run with money from the government, so I guess there must be at least a thin connection between this and art without content. Luckily, there are other young artists working in different directions, like Nuria Güell or R. Marcos Mota.

DB: You are setting onto a very exciting leg of your journey and much can happen for you in the nearer and further future. Where would you like to be in 5 years (physically and metaphorically)?

DO: First, I want to see my family, whom I haven’t seen in three and a half years. I hope to find a way to work in a less confrontational way, simultaneously more reflexive and active. Pedagogy as a practice is something I’m very interested in, and I also want to continue studies in critical theory. That’s why I am interested in Mexico; there are platforms there such as Campus Expandido at MUAC (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo) that offer a very solid critical education from the perspective of the periphery. I would like not to have to rely on Europe, finally.