As I am grieving the disappearance of the Minimalist from the pages of the New York Times, I am also pondering Mark Bittman’s statement from his farewell column, “the continuing attack on good, sound eating and traditional farming in the United States [and elsewhere in the world, I want to add] is a political issue.”

“Relational art” and especially the stardom of Rikrit Travanija, has made food one of the hot topics of contemporary art. Food has been re-discovered and celebrated as a means of bringing people together and creating experiences of genuine sharing and fair exchange. These optimistic notions and projects tend to overlook – to paraphrase Eric Schlosser – “the dark side of the contemporary meal,” which persists even despite the efforts of the Slow Food movement or First Lady Michelle Obama. Even more rare are artistic proposals that try to engage the dangers and inequalities lurking behind what and how we eat.

One of the little-known exceptions is the recent work of Peruvian artist, Eduardo Villanes (born Moscow, 1967), whose projects ponder the loss of the incredible biodiversity of his native land, the ancestral home of more than 600 varieties of potatoes and endless amount of other plant and animal species. Especially fascinating about his case is not only the content of his current enterprise, which puts genetic modification and patenting of crops by transnational corporations at the cross-hairs of attention, but also the particular tension that exists between Villanes’s recent work and his earlier proposals developed in the 1990s. This peculiar conflict offers an opportunity to consider two important issues: first of all, how we get acquainted with art, what we see, when and why we see it; and secondly, how complex and ambiguous the process of historicization of a living, producing artist can be.

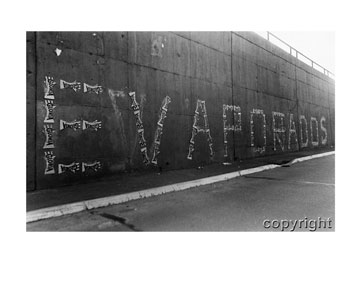

Eduardo Villanes, "Evapordos," mural intervention in Via Expresa, Lima, Peru, 1995. Courtesy the artist.

The 2010 acquisition of Villanes’s documentation of his 1994/95 series of projects Gloria Evaporada by MALI (Museum of Art of Lima) ultimately canonized them as milestone accomplishments of the decade. These ingenious works, conceptualized and realized through common cardboard boxes for a can of evaporated milk called Gloria, were an audacious response to one of the most infamous cases of forced disappearances during the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000) in Peru. The dramatic context of their conception as well as the tactics employed by artists inscribed them into a long tradition of Latin American Conceptual Art, and the documentation ended up being featured in the seminal exhibition of performance art in the Americas, Arte ≠ Vida, at El Museo del Barrio in 2008. Well-known, albeit not necessarily thoroughly understood, the Gloria series, which barely survived the historical upheaval of the turn of the millennium in Peru and Villanes’s subsequent exile to the US, remains legendary among the younger contemporary artists in the country. As I am writing this text, it is one of the highlights of MALI’s new acquisitions’ exhibition, together with another crucial project of the same period, Ricardo Wiesse’s Cantuta.

Paradoxically, just a few months before, in June of last year, one of Villanes’s new projects, La Extinción del Maíz (The Extinction of Corn), became a bone of discontent between the artist and Fundación Telefónica, one of the premiere, new media-focused, exhibition venues in Lima, who had invited him to mount a solo show in one of their galleries. Unwilling to accept the artist’s text accompanying the work, the officials of the Foundation decided to remove their logo and exhibition title as well as information about the location and opening hours from the catalogue, and presented this stripped-naked publication at the show’s opening reception. Villanes, who had previously suggested inserting a standard disclaimer into the catalogue, was outraged. As he considered the decision to be the gesture of (auto)censorship (it prevented the public who might have seen the publication elsewhere from encountering the actual work), he decided to take his show down.

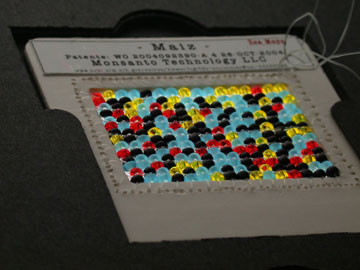

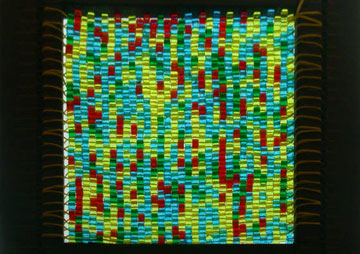

You may wonder what caused the administrators’ of Telefónica to be so uncomfortable that they resorted to taking off their name from the exhibition’s catalogue. At first glance, Villanes’s works dealing with GMOs appear quite benign: seductive, highly optical creations, rather than dry, conceptual political pieces. For the past few years, the artist has been translating DNA sequences of variety of plant species into four-color patterns (which each color standing for one of the four DNA nucleobases: adenine [A], cytosine [C], guanine [G] and thymine [T]), which he later materializes as what he calls “microtextiles,” or beadworks, tiny pieces of fabric woven with thin nylon string and glass beads. The fabrics are then installed in slide mounts and either displayed on light tables or – enlarged multiple times – projected onto the walls of a gallery. The Extinction of Corn took on the latter form, presenting itself as an alluring spectacle of luminous, vibrant colors totally consuming the exhibition space.

Yet, this lush image was also injected with a bitter medicine. The artist statement published in the exhibition catalogue unequivocally condemned genetic modification of living organisms and corporations standing behind mass implementation of GMOs into industrialized agriculture. However, what overfilled the cup for the Telefónica’s officials was the last sentence of the text that likened an assassination of an American Indian opposed to the opening of casinos on his reservation to “what is happening now in the Peruvian jungle.”

From a distance, the phrase that stirred the controversy must seem oblique and extremely vague. For the savvy in Peruvian society and politics, however, it evokes recent violent conflicts between the government and indigenous tribes (and specifically bloody massacre in Bagua in June 2009) over the rich in natural resources land of the selva. Neo-liberal policies, encouraging the use and industrial extraction of valuable goods, especially natural gas and water energy, by foreign corporations clash with the local way of life, dependent on the incredible nutritional and medicinal value of the immense variety of the plant species of the forest, where the bond with nature has multiple sacred dimensions. Villanes, who spent long periods of time in the jungle in the second half of the 1990s, is obviously concerned with the cultural and spiritual heritage of the local traditions and, not without a reason, extends his focus onto the issues that impact us all, regardless of the current place of residence: agriculture and food.

The artist’s meticulous beadworks stem partially from the research work that he has undertaken in the US Patent Office, learning about specific alterations to the DNA chains of the traditional plant species and discovering the overwhelming number of patented seeds. To his dismay, Villanes found out that scores of indigenous American edible plants have been patented, including not only corn and potatoes, but also such staples of traditional Andean agriculture from Inca times as quinoa and amaranth. Therefore, aside from the luminous projections, this information finds also more direct and more activist outlets in form of the artist’s e-mail campaigns and silk screens, often laced with extremely direct, sometimes bitterly humorous imagery.

Eduardo Villanes, "Monsanto Comemaiz," screen print on cornflakes box, 17.5" x 16.25", 2010. Cortesy the artist.

From the perspective of this critical writer, Villanes’s beadworks pose scores of challenges, as highly ambiguous and contradiction-laden creations. Their form is utterly sensuous and seductive, which allows one to charge them with excessive aestheticism. Simultaneously, they rely on ancient, traditional technique and make covert (and impossible to decipher for a non-specialist) reference to Andean textiles as a particular form of a proto-database. In addition, in their presentation, they rely on obsolete, antiquated modern classroom technology: light-tables and slide projectors (Villanes also used them to produce videos and animations though). If all of those external factors were not enough, they stem from a deep engagement with the one of the most controversial, even if sometimes overlooked, topics of today’s world — encoding within their alluring, kaleidoscopic appearance mutated genetic codes, the full impact of which is yet to be discovered. But is this sufficient to explain why, even in his native country, it is so difficult to see this work?

Since I first became familiar with Villanes’s artistic production and started analyzing the phenomenon of his Gloria (which ended up one of the key works of my MA thesis), I was perplexed by the way in which it was being celebrated in Peru. Surely, on one hand, it does fit the canon of the conceptual and post-conceptual protests works about Los Desaparecidos – today, a romanticized myth of the continent, as the artist himself sees it – that perhaps earned its inclusion in El Museo del Barrio’s exhibition. Yet, some very vocal local critics more often present it as a pioneering new-media work (exhibition Gloria Evaporada included two performances for video and also a crucial sound element evocative of Robert Morris’s The Box with the Sound of Its Own Making), introducing the contemporary genre into the provincial art scene. Can Gloria be seen in the Museum today not only because of historical distance permitting its cool-headed evaluation, but also because of the fact that its immediate political concern has been effectively neutralized? And is it possible that in today’s atmosphere the visually seductive beadworks are simply too hot to handle? Perhaps, time will tell.