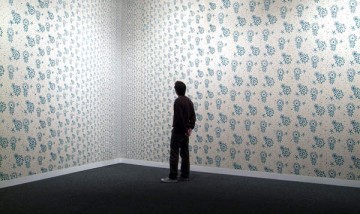

Jorge Macchi, "Vanishing Point," 2005. Acrylic paint on paper. Variable dimensions. Collection of Michael Krichman and Carmen Cuenca, San Diego. Via hammer.ucla.edu

“It’s really about the magical and the mysterious in the everyday,” says Hammer senior curator Anne Ellegood, in the online video introducing the museum’s newest exhibition, All of this and nothing. Ellegood worked alongside chief curator Douglas Fogle to select artists who use mundane moments and everyday materials to delve into complex existential explorations. The contemplative, delicate quality of most works in the show belies the diversity and complexity of the exhibition, which includes 60 works by 14 different artists from all over the globe.

Buenos Aires-based artist Jorge Macchi uses tropes of ordinary life and castoff objects to delve into ideas of entropy, eternity, and mortality. Vanishing Point is comprised of two walls, adorned with trompe l’oeil hand-painted wallpaper. The patterns get smaller and denser as they approach the corner, creating a forced perspective illusion in which the gallery seems to proceed toward infinity. In Parallel Lives (1999), Macchi smashed a mirror using a hammer and nail. The mirror remained relatively intact, but cracks radiate erratically from the point of impact. Macchi then painstakingly chiseled cracks into an identical mirror, creating precisely the same cracks as in the original mirror. For Monoblock, Macchi extracted death notice pages from the paper, cutting out the rectangles of information about each individual and leaving only the symbol of his or her religion – typically a crucifix or star of David. The pages are layered upon one another, peeking through one another’s cutout windows. Devoid of text, the yellowed stack of papers, hanging vertically on the wall behind a glass frame, has the feeling of an architectural rendering. Each empty rectangle hangs like a vacant room. Out of context, all the tiny crosses and stars swell with mystery.

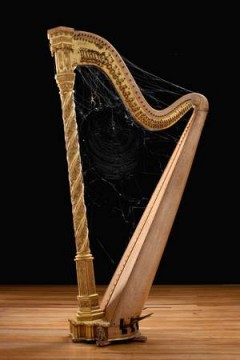

Fernando Ortega, "N. Clavipes Meets S. Erard, Movement 3," 2008. Photographic print. Courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Via hammer.ucla.edu

On the other side of Macchi’s faux-wallpapered partition, Mexico City’s Fernando Ortega gracefully wrestles with similar ideas of chance, emptiness, and temporality. In 2008, Ortega offered a skeletal harp frame, sans strings, to a single spider. With some nudging, the spider eventually spun a web in the negative space of the harp, restringing the instrument with its delicate web. Generally a symbol of heavenly divinity, the harp stands in contrast to the web and spider – which typically signify musty neglect in the most benign sense, and familiars of the spooky occult in darker interpretations.

The counterintuitive muteness of the harp is echoed by Ortega’s adjacent video piece, Hummingbird Induced to a Deep Sleep. As the title suggests, Ortega has documented a tiny hummingbird perched on a branch with eyes shut, its typically-frenetically fluttering wings silenced by stillness. With the bird perched on a leafless branch, its jewel-green feathers contrasting sharply with the empty white background, the video feels at first like a photograph or even a colored drawing. The tiny creature barely moves, except to heave its round little chest every few minutes. Unlike the mythologized shark, hummingbirds apparently do stop moving to sleep, but we rarely glimpse the typically hyper-hued and hyperactive creatures unless they are in motion out in the open. Seeing a hummingbird with no hum feels uncanny and forbidden.

Fernando Ortega, "Hummingbird induced to a deep sleep," 2006. Video, color, silent. 61 minutes, 37 seconds. Courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Via the Hammer Museum.

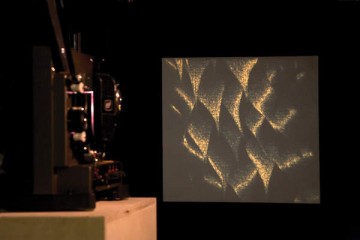

Los Angeles artist Kerry Tribe explores history, cognition and subjectivity, typically through complex narratives that combine personal stories with political dramas. However, one of her three pieces presented in conjunction with the Hammer’s exhibition, entitled, Parnassius Mnemosyne echoes Ortega’s works with an unusually simple gesture based on nature. Entering the dimly lit lower gallery at the Hammer, the viewer is confronted with a darkened room, a film projector, and a freestanding screen. The movie pans slowly and repeatedly across a patterned surface that seems at once abstract and distinctly biological. The true subject may not become clear until the viewer exams the wall text, spot-lit within the dark space.

Kerry Tribe, "Parnassius Mnemosyne," 2010. Installation view. Image courtesy hammer.ucla.edu

The supplemental narrative explains that Tribe was attracted to a Vladimir Nabokov drawing of the Parnassius mnemosyne butterfly. Nabokov is known for moonlighting as a lepidopterist. In fact, his previously disregarded theory of butterfly evolution was serendipitously vindicated one week prior to the opening of the current Hammer exhibition. In any case, Tribe was particularly inspired by the butterfly’s scientific name, derived from the Greek goddess of memory—a prominent thread throughout her work. The magnified image of the butterfly wing slyly inverts with each passage through the film looper, a function of the Möbius strip-contortion of the film itself. This barely-perceptible inversion simultaneously resonates with nature’s mirroring within each pair of butterfly wings, and the distortion of human perception, cognition, and memory.

Other standouts include Charles Gaines’s scrolling musical scores derived from four different twentieth-century political manifestos, Karla Black’s giant, disorienting installations of plaster, bath bombs, soap and plastic, and Dianna Molzan’s re-crafted and distorted canvases, which gracefully echo human flesh while responding cerebrally to art history. While ambitious exhibitions organized around a thematic principle often fail to deliver, All of this and nothing feels harmonious and unified. Perhaps due to the lens of mundanity, most of the work succeeds in stirring up philosophical questions without resorting to heavy-handedness.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Looking at Los Angeles | Ephemerality and Eternity in “All of this and nothing” | Art21 Blog -- Topsy.com