Roy Stryker, the man who ran the Historical Section of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and sent some of the best-known 20th century photographers out on their first assignments, “didn’t give a damn about a picture at the time it was made.” According to aerial photographer Charles Rotkin, he began archiving before the photos had even been made, “saving pictures for a record of the past.” An economist at Columbia University before his appointment to the FSA, Stryker knew next to nothing about the mechanics of photography, but he knew what he wanted the present to look like in the future. And what he didn’t want it to look like.

Stryker adopted a habit of “killing” images he didn’t approve of, punching a hole, often right in the center, in a negative, and, since FSA photographers didn’t own rights to their images and sent negatives to DC to be processed, these holes really did “kill,” rendering images effectively useless (Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans likely protested the practice–both took vehement issue with Styker’s treatment of their work during their FSA tenure).

Not long ago, L.A. artist and filmmaker William E. Jones came across Stryker’s holes while digging through the Library of Congress’s archive. He became intrigued, both by the power Stryker exerted over his photographers and by the holes themselves. Decisive, efficient, and yet often totally nonsensical given the context of the images, the holes themselves become the focal point in Jones’s two recent videos, Killed and Punctured, both of which cycle through a series of would-be canonical, now-damaged FSA images.

Jones presented his two films at University of Southern California’s School for the Cinematic Arts last Thursday, March 3 (he also showed them at Andrew Roth Gallery in New York and, a few months ago, at MoCA). It was excess that Stryker often seems to be punishing, Jones observed during the post-screening Q & A; three takes of a girl and a cat are all killed, as are other instances of needless repetition (needless by miserly standards, that is—as Jones pointed out, girls and cats rarely sit still).

It’s the excess Stryker punished that comes to represent him in Jones’s work. The black holes become embodiments of his idiosyncratic censorship and the images feel like victims of one man’s erratic sense of propriety and usefulness, which is likely not what the economist-turned-legacy-maker had in mind when he started punching holes.

There’s something irreverent and empowering about taking excess, or what’s beside the point, and making it the point, especially when an excessive non-point becomes compelling in itself. Richard Hawkins does this in his current exhibition Third Mind (the title alone connotes extras), which recently arrived at The Hammer via the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s a smartly indulgent show; the works in it are culturally obsessive, and seductive nostalgia and teenage, faux-tortured lust are used as aesthetic strategies. But ultimately, Hawkins is a minimal artist who pares obsession down until they become as precise and incisive as possible.

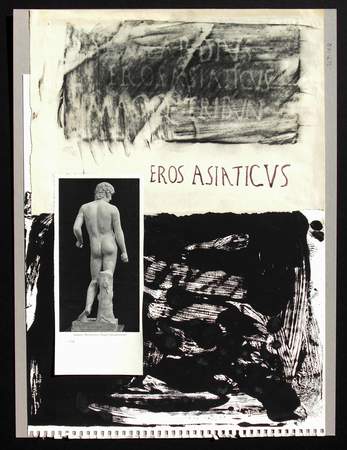

Richard Hawkins, "Urbis Paganus IV.8," 2009. Charcoal, oil, watercolor and collage on paper; and mixed media on matte board.

One particular series, called Treatise on Posteriority, fixates on the backsides of Greek and Roman sculptures. The series includes collage images of classical statuary next to carefully composed text (“There are some [artists] who reward the effort it takes to read while standing up,” wrote Ken Johnson in the New York Times, adding, “Richard Hawkins is one.”) Urbis Paganus I V.9.III shows the sculpture Doryphoros, of an athlete with a spear balanced on his shoulder, next to this musing:

Roman Statuary is oriented always toward the front. Toward name, toward face, and ultimately toward recognition—that’s its purpose. So why does it even have a backside? Particularly one as finely worked and delectable as the one pictured here?

Why indeed? And why did Stryker, who wanted to ex the images that didn’t fit into his plan for posterity allow these same images to live on, even in their killed state?

In confusing posterity with posteriority, Hawkins points to what’s always been there: a back story (one that’s error, desire, deviance, and idiosyncrasy doesn’t do much for great civilization narratives). By circulating the photographs Stryker punctured, Jones essentially does the same.