Ever watch a three month old baby stare into a mirror for the first time? Its face is an expression of pure awe and confusion. What is the thing in the mirror? Why isn’t it like me (three dimensional)? Over time, of course, that curiosity turns into fascination at the stage when the child learns that the image he sees is himself… or, at least, the image of himself. That recognition may seem trite but it is a critical site in the individual’s subjectivity-formation. At this level there is still much play and experimentation as he learns how to be and how to identify himself in relation to others.

How we self-identify relative to others is a key issue of exploration for Vancouver-based artist Ken Lum. Lum’s retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery involves several installations using mirrors as well as riffs on public signage that create what he refers to as “triangulation”: a visitor is always projecting his or her own identity onto characters on a sign or poster. A kind of looped communication occurs between expectations, projection/reflections, and identification. These works by Lum are focused on issues of identity, evoking empathy at the same time as alienation.

In the Photo-Mirror series Lum began in 1997, the viewer walks into a room where personal-use mirrors hang. Wedged on the inside edge of each mirror’s frame, photos of random people and scenes stick out — strangers smiling in seventies school studio portraits, eighties birthday shots, and scenes of backyards and beautiful sunsets that belong on postcards. As the viewer amusingly looks at his own reflection in the mirror, his face is quite literally framed by the small photos of other people looking back at him. A series of reflections in a room of mirrors could go on forever. We get the metaphor. But here, also, art gets to perform its occasional magic by debunking common sense, replacing it instead with what Gilles Deleuze prefers to call “good sense.” Good sense, as opposed to common sense, is where “difference exists at the origin of individuation,” and the subject’s sense of what is is defined by the process of prediction, rather than recognition. I don’t actually recognize the smiling faces in the portraits but they are ubiquitous nonetheless. Unrecognizable but familiar. I’ve got the same (but different) photos in my roster of old photo albums at home.

In my conversation with Ken Lum for Radio Canada International, he shared that he aims to “destabilize the position of the viewer.” While it’s not possible to consciously return to a state of presubjectivity (like the infant in front of the mirror), destabilization is possible. A museum is already a public space for private contemplation. It operates on a code of social conventions when it comes to invading others’ personal space. This dynamic is exacerbated in a room where the visitor awkwardly stares at reflections of himself — a highly personal experience — but in public. Lum’s recontextualization of an everyday object reveals a certain continuity of feelings of amusement as well as anxieties across various social strata that form (and inform) the way people live ordinary lives.

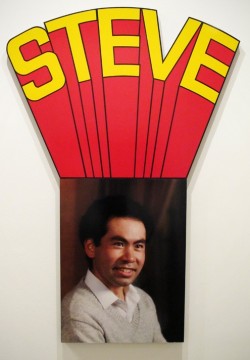

Installation view. Ken Lum, "Steve," 1986. Photographic c-print on photo paper resin coate, acrylic sheet. Courtesy Bob Kronbauer and VancouverIsAwesome.com.

Lum’s Portrait-Logo series takes conventions of common studio portraiture (professional lighting, individuals dressed and groomed to impress) to an extreme. In Steve (1986), a large (one square meter) print, the subject’s name seems to cartoon-explode from his head in a loud, radiant font; its spirit is celebratory, as though Steve were an award-winning entrepreneur or better yet, just someone important. The implication is, of course, that Steve matters, ordinary as he may be.

Casting an East Asian man as the subject of Steve is intentional and interesting, especially as Lum produced the work in the mid-eighties when the image of an East Asian man in Vancouver heralded on a poster would have occupied an ambiguous political and social status. Many East Asians by that point in Vancouver were either immigrants themselves or sons/daughters of immigrants if not grandsons/grandaughters. For that demographic cohort, the game was much about ease of assimilation. “Steve” could likely have been a first or second generation Canadian and as such could easily have faced feelings of exclusion and isolation trying to fit in to what was then a predominantly (though changing) mostly English-speaking Canada. In talking about Steve with me, Lum mentions a memory from his childhood in first grade, when his teacher was asking him a question in English and he hadn’t yet learned the language and thus had no idea what the teacher was saying. Lum calls the event “traumatic.”

The anecdote is a reminder of what the iconic-like image of Steve represents. After all, what is being fêted in the poster image of Steve? Is it Steve’s ability to conform to ubiquitous conventions — be fashionaby dressed, appear happy, etc.? Or perhaps is it society’s successful amelioration of Steve into the fold of mass and popular culture? Is this a poster for the Canadian Multiculturalism Act?

-

Lum has said that his work has “always had a public address to it.” Lum tells me he considers himself an “empath,” and the descriptor is a fair one in his case. He says he absorbed the quality of empathy from his Buddhist mother who, while she was alive, worked strenuously as a manual laborer in a suburb of Vancouver. As a child, Lum had hoped to get his parents out of poverty and faced disappointment from them that he was not pursuing a more professional career. That Lum went on to create works about existence and identity is fitting. There are moments in viewing his works where a sense of social justice triumphs; where a voice is imagined for characters often absent from popular images and public discourse, including archetypal working-class individuals.

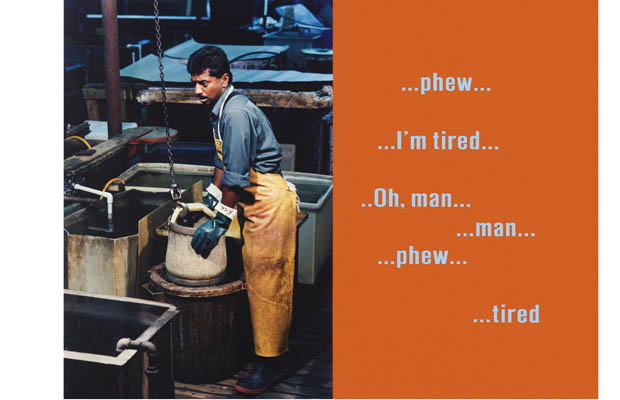

Ken Lum, "Phew, I’m Tired," 1994. Chromogenic print, aluminum, enamel, Sintra. Collection of the Vancover Art Gallery; courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery.

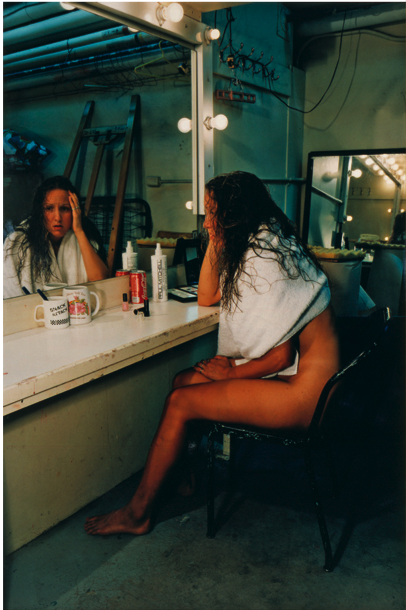

Lum’s Portrait-Repeated Text series puts ordinary people on the front of billboards and in the center of signs juxtaposed with messages of uncertainties and inadequacies. However, in our interview, the artist reminds me that it is the viewer who ultimately projects his own experiences on an understanding of the subject’s woes. One possible narrative pairs an image of a South Asian worker alongside text that reads “phew…I’m tired… Oh man…man…phew…tired.” In another image, a partially-naked woman rests her head on her hand in what looks like a dingy dressing room.

In effect, these works provide a kind of history for Vancouver, where these stories – the less obvious ones of everyday hardship and mundanity – can lack representation in the public sphere.

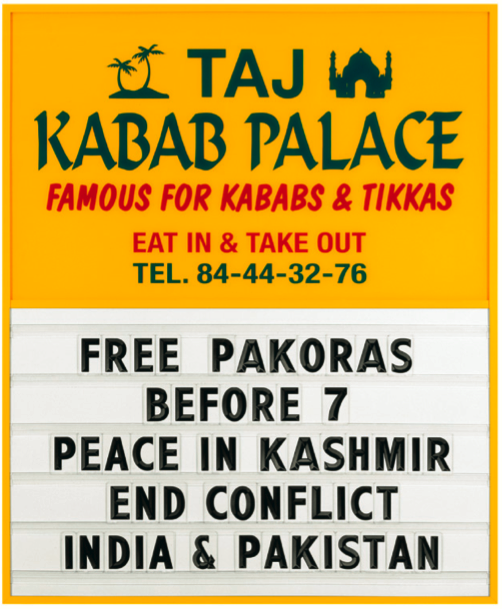

Lum’s Shopkeeper Signs series consists of low-end fictional retail advertising signs imbued with social, political, and personal messages that often (but not exclusively) deal with the complex place of newcomer status in Canadian society. The signs themselves look like legitimate business signs you might see outside a small business while driving through a town. But it is their text that sets them apart. One sign reads: “Taj Kabab Palace Free Pakoras Before 7 Peace in Kashmir End Conflict India & Pakistan.” “McGill & Son Paper and Printing” announces the moving words: ”To my valued customers: My son is no longer my son.”

While it can be said that Lum is one of Canada’s most internationally-known artists working today, his retrospective is a special one for Vancouver. This survey of over thirty years of work finally establishes “Ken Lum” as a household name at home, in the very city which he proudly shares as inspiring most of his work. And although some of the works convey bleak or disparaging scenes and are embedded in fictional narratives, they are also small celebrations of the city of Vancouver and a tribute to the differentiation it has engendered in its young history.

Pingback: Just starting out…

Pingback: Ken Lum

Pingback: Creolization: Millennial Words | FINE 307- Art & Text