* This interview has been translated and co-edited by Brian Whitener.

I first heard about Colectivo Situaciones about a year ago, when I received a publication in the mail titled Genocide in the Neighborhood, edited by the scholar and poet Brian Whitener and translated by Whitener, Daniel Borzutsky, and Fernando Fuentes . This book, published by Chain Links and available through Small Press Distribution in Oakland, focuses on three organizations that emerged during the mid-90s and early 2000s in Argentina: Colectivo Situaciones, HIJOS [Children for Identity and Justice against Forgetting and Silence], and Mesa de Escrache. Though a series of conversation and interview transcriptions as well as collaboratively written documents, Genocide in the Neighborhood tells a story of how these groups came to work with various neighborhood communities throughout Argentina in the interest of bringing the crimes of both the Argentine dictatorship (1973-1983) and subsequent governments that granted immunity to many who had committed crimes against humanity during this period to light. As the children of the “disappeared,” those who were executed for their political sympathies during the dictatorship, Colectivo Situaciones and their colleagues have sought a kind of justice through a social practice that emerges through their efforts: the escrache. As Whitener writes extensively of the escrache, a ritual performance situated within specific communities that attempts to exact alternative forms of justice in the interest of community building and healing:

Like all truly innovative practices, what the escrache is is rather difficult to define; it’s something between a march, an action or happening, and a public shaming. The escraches are a transformation of traditional forms of protest and were developed as a means to address two problems. The first was the problem of “impunity” [the granting of legal immunity to criminals of the dictatorship]; the second was the loss or suppression of historical memory that this legal reality created.

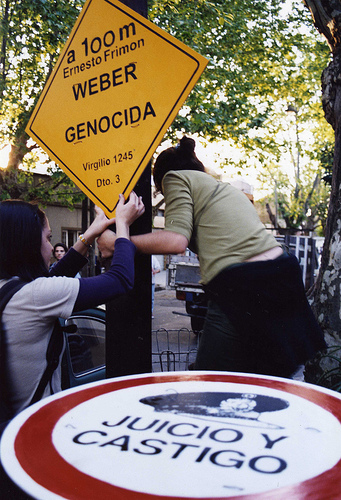

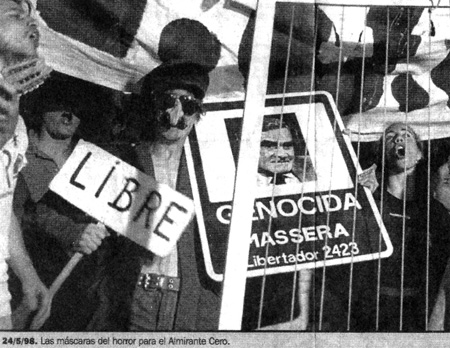

The escrache, then, as a practice looks like this: HIJOS selects someone who, during the dictatorship was responsible for or complicit with the torture and murder of people, to be escrached. When they first started, HIJOS targeted high-ranking members of the dictatorship, who primarily lived in the center of Buenos Aires. Later, a decision was made to escrache lower ranking members in part to begin to work in other parts of the city, but also to demonstrate that members of the dictatorship were living as if nothing had happened. Once a genocidist is decided upon, a date for the escrache is fixed and members of HIJOS and other related organizations spend months working in the neighborhood where this person lives. They work with neighborhood organizations and go door-to-door to discuss with individual residents and families what that person did and the need for denouncing it. They also discuss the theory and practice of the escraches. Next come months of flyering in order to invite and secure participation of the residents of the neighborhood in the march, which is part of the culminating action of the escrache. The march leads the neighbors to the criminal’s home, where there are theater performances and a symbolic ‘painting’ of the house. This ‘painting’ usually involves throwing paint ‘bombs’ or balloons at the building in order to mark it as the genocidist’s place of residence. The idea is to once again transform the space of the neighborhood, to make visible that genocidists still walk free.

As Whitener goes on to say in his introduction to Genocide in the Neighborhood, the organization of such public and communally immanent rituals, while it takes on aspects of the “happening” or “situation,” is in the service of exploring inter-actions and relations within specific communities that may help to transform those communities positively, towards productive expressions of political and juridical power. Where the state judiciary has failed the people of Argentina (much as our own public officials now fail us in the US), Colectivo Situaciones and their affiliates seek forms of justice and politics that are not a priori but rather are conceived through a rigorous and extensive social process. The result is a practice of “social protagonism” and the construction of “plane[s] of social transversality,” a space in which individuals and groups can explore forms of subjectivity and potentiality autonomous to the seeking of state power. In the wake of Colectivo Situaciones, one can start to imagine how art and performance can serve politics through commitments to the local, particular, and relational — which is to say, through a commitment to working with the people whom their art would be for, whom it would serve.

Transforming the visual space of a neighborhood (escrache of Weber). Courtesy Colectivo Situaciones.

1. What inspired you to start Colectivo Situaciones?

Because the appearance of a new social protagonism in Argentina demanded inventing new forms of thought and political practice. Because the ease of the academy bored us and the utilitarianism of traditional (Right and Left) politics made us indignant. Argentina suffered a long period of neoliberal rule during the final twenty-five years of the twentieth century. The changes in social structure introduced during this time were, in large measure, irreversible. The idea of a social transformation that might emerge from the popular sectors was defeated and appeared to no longer have any purchase on reality. During these years, the process of democratization generated by national political and economic elites was fundamentally cynical in nature, and the critique and desire for emancipation were sustained in what were, for the most part, very conservative forms.

Out of this rather bleak context, during the mid-90s, practices of resistance of a new type began to emerge in Argentina, ones that utilized original forms of struggle and mechanisms of organization. Here, a new political subjectivity was germinating. The dogmas of the Left, the misery of their institutions and the rigidity of their intellectuals only contributed to marginalizing these practices. In the place of unions, movements of the “unoccupied” (unemployed) appeared; in place of new educational models, forms of educational autonomy were discussed and popular education programs spread; beyond the movements of the market, barter networks emerged and workers took charge of bankrupted factories which were then abandoned by their owners; moreover, out of human rights organizations appeared the escrache, a practice of popular justice (a story that is told in a co-investigation conducted with HIJOS, a human-rights organization based in Argentina and recently translated into English [in] Genocide in the Neighborhood). All of these practices shared the same motto, one first heard in the mountains of southwestern Mexico: ya basta (enough!).

Militant investigation, the practice we developed along with other collectives, was in this moment not only a mode of composition with these and other experiences but, at the same time, a means of intervening in the field of the production of knowledge and political hypotheses. The combination of all these impulses and practices under a form of horizontal cooperation brought the neoliberal project in Argentina to crisis, which became a massive insurrection in December of 2001, and caused a deep historical shift in Argentina and across the region.

“Genocidist on the Loose”: Hanging signs in a neighborhood before an escrache. Courtesy Colectivo Situaciones.

2. Why do you feel there to be a need for organizations like Colectivo Situaciones, which produce aesthetic objects and actions that intend a direct effect upon their social contexts (if that’s how you’d describe what Colectivo Situaciones does)?

If you mean by “aesthetic objects” what we would call “conceptual images” (new configurations of subjectivity that express a collective imagination), then militant investigation could be considered like that. “Conceptual images” are an important idea for us because when these types of organizations multiply, it makes possible a transversality that allows for the constitution of an autonomous public sphere (a space or set of sites outside of state and corporate control where persons and groups can create their own forms of life and thought) . The construction of an autonomous public sphere is before all else a work of political configuration, of organization amongst collectives and social movements. One can say as well, at least in our experience, that such a sphere doesn’t require a subject capable of guaranteeing its consistency. On the one hand, then, there is autonomy when a plane of social transversality is constructed, from which the multitude elaborates and intervenes in matters of common interest, putting into play an imagination that is flexible and horizontal. On the other hand, perhaps the most legible sign that we are inside a process of political innovation is the fact that no one remains exempt from recreating [his or her] own subjective disposition. Each collective subject and each personal trajectory become indices of the verification of the vitality of the social change that is in process. The experience of autonomy in which we participated in Argentina during the years 2001-3 was, bit by bit, undone by a progressive program of stabilization that did meet certain demands of these social movements, but which also reasserted the institutional structures of the state as the privileged site for collective decision-making. This doesn’t mean, however, that in other moments a constituent horizontality cannot return.

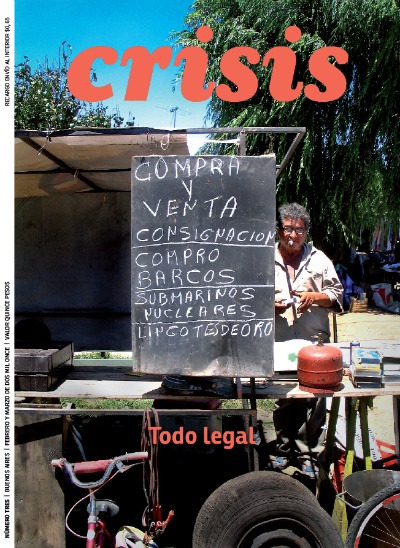

"Crisis": a new magazine produced by members of Colectivo Situaciones. Courtesy Colectivo Situaciones.

From the point of view of our collective’s journey, perhaps our work (always undertaken with others) has been to propose various conceptual images that have emerged out of the very unfolding of these social struggles. The first of them, the notion of militant investigation, was a search for anti-academic knowledges and ways of acting outside traditional politics, with their hierarchies and utilitarianisms. At the same time, the encounters that we organized with practices and thinkers close to us allowed for the emergence of certain hypotheses, some more directly practical and others more theoretical.

We can give three examples. Popular justice and the escraches, which were directed at the construction of a form of “social condemnation” for the perpetrators of state genocide during the dictatorship, proposed the idea/image of counterpower as an immanent strategy of organization. Out of other conversations, the idea/image of a new social protagonism emerged in order to name the multiplicity of subjects that were appearing during 2001 while avoiding both sociological categories and the permitted figures of the traditional revolutionary Left. And finally, out of the movements of the “unoccupied” (desocupados), the mere fact of daring to demand employment had a powerful force and launched a trenchant critique of labor.

The artistic collective Etcetera from a newspaper photo of the escrache. Courtesy Colectivo Situaciones.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired Colectivo Situaciones (past or present)? Please describe.

The list would be infinite. Just to mentioned a few political and theoretical influences: the long history of radicalism in Latin America thinkers like the Peruvian Mariategui, Che Guevara, Zapatismo, the Argentineans John William Cooke and Leon Rochitzner, the feminism of Mujeres Creando, the force of contemporary social movements [the piqueteros, the indigenous movements of the Andes (altiplano), the campesino and environmental movements]. On an aesthetic terrain, our principles influences are Grupo de Arte Callejero and the work of the Brazilians Sueley Rolnik and Peter Pal Pelbart. Other intellectual influences are the thinkers of Italian autonomism (Toni Negri, Michael Hardt, Paolo Virno, Sandro Mezzadra, Bifo, Maurizio Lazzarato, etc.), the Catalan Santiago Lopez Petit, the philosophy of the generation of May ’68, Marx and Marxist thinkers such as Walter Benjamin and Sartre, and the philosophy of Spinoza.

In particular, the work of Grupo Arte Callejero has been very important to us (their book is Pensamientos, prácticas y acciones). The idea of assemblage, first developed by Deleuze and Guattari and taken up more recently by Maurizio Lazzarato (in his book Políticas del Acontecimiento or Politics of the Event) has been important as well. The audacity of the graffiti of the Bolivian feminist collective Mujeres Creando and the philosophical work of María Galindo form part of our theoretical background (see our book written with them, La virgen de los deseos). The idea of fragility proposed by Suley Rolnik has been in the center of our work for a long time now (see especially her book Micropolitics) as has been the idea of affective tonality, developed by the Peter Pal Pelbart in his book Filosofía de la deserción. We could also mention the work of Eduardo Molinari and his idea of the Archivo Caminante (Walking Archive) and his work with us in the book and audiovisual archive Mal de Altura. Viaje a la Bolivia Insurgente (Altitude Sickness: A Journey to Insurgent Bolivia). And more recently, we have been influenced by the concept of chixi as developed by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui in her book Ch´ixinakax Utxiwa. Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores (Ch´ixinakax Utxiw: A reflection on decolonial practices and discourses). As we said at the beginning, the list is interminable!

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

Our project is composed by projects that are not created a priori but that emerge from experiences that we live and that seek to identify a common field or ground amongst contemporary collectives or social movements. For example, our work with the desocupado (“unoccupied” or unemployed) or piquetero movements, with the children of the “disappeared” (HIJOS and the escraches), with Latin American social movements, with street artists, with radical education projects has always been undertaken with these collectives and with the idea to try to identify a common figure that might traverse them.

Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui Ch´ixinakax Utxiw: A reflection on decolonial practices and discourses. Courtesy Colectivo Situaciones

5. What projects do you see in the future for Colectivo Situaciones? What direction would you like to take the organization in?

The most important challenge we are currently facing is the opening of a social space (a house) in Buenos Aires that will house the network in which we are currently participating. The intention is to create a new post-state (pos-estatal) institutional space with the idea to reopen cooperation and the political process in Buenos Aires. We are also working on a co-investigation with Bolivian friends who live in Buenos Aires and we are exploring new publishing initiatives.

For us, it is fundamental to re-work the ideas, concepts and images that emerged from our immediate experience. The current conditions in Argentina, first and foremost seen in new forms of governmentality that recognize and work from the reality produced by the struggles of 2001-3, have changed in a profound manner. And this can be seen in two shifts that have occurred: the first is the return of the “political” as the critical site of action (as opposed to an autonomous public sphere) and of the state, the parties, and unions as the key actors (as opposed to the social movements of 2001-3) but also we have to recognize that the mechanisms of struggle and thought that were created by the social movements of 2001-3 are no longer functioning, no longer efficient. As a result, we believe that is it necessary to construct ways of intervening collectively in these current conditions. But this doesn’t mean that we have to begin again from scratch. There is the experience that each of us carries with us and the networks that continue to be created. It is because of this that we are trying to create a collective space (a house) that would allow for the construction of a form and content that could trace the outlines of a new type of post-state institution. A space capable of containing and activating the initiatives of this network (that include educational practices, work with Bolivian immigrants, struggles against the exploitation of migrant workers and community resources, projects concerned with the demedicalization of healthcare, projects with the young in the ex-urbs of Buenos Aires, and a publisher of books, magazines, radio programs, video work, etc). A space that could construct a new platform of autonomous enunciation and visibilization that would be capable of subtracting itself from the semiotic regime of the media and the biopolitical treatment of these problems in their state form. A new public space in which to process and overcome the current impasse (see our text, in Spanish, on the nature of this impasse; or in English) of autonomous practices that could subtract itself from the media-politics polarization that current dominates the scene. This is our most important challenge in this moment and it is a very real challenge: construct a network of groups with very heterogeneous experiences and develop a constructivist thought concerning the nature of these types of linkages.

Pingback: rebel:art » Blog Archive » Und sonst so: 20.03.2011