What does it mean to sing a protest song as if it were a lullaby? It’s a question I often ask myself. My five-year-old daughter has trouble falling asleep at night, so most evenings, my husband stays with her until she drifts off to never never land. He has a little trick he uses to help her relax: he sings her a song by the Cowboy Junkies called “Mining for Gold.” The song was written by the Canadian folk musician James Gordon, who in turn based it on a traditional song called “Taku Miners.” Yet it’s Margo Timmins’s swelling a cappella version that has made this song such a memorable one (compare it, for example, with this rendition of “Taku Miners,” which, following the original, is set to the bouncy tune of “Darling Clementine”).

Although I guess it’s not technically a protest song, Timmins’s “Mining” does express that complex blend of pride, stoicism, and human yearning from which protest often springs. Margo, Michael, and Peter Timmins are the great-grandchildren of a well-known Canadian mining prospector, so no doubt they were thinking of their own family’s heritage when they chose to cover the song for The Trinity Sessions. My husband and I realize that it’s kind of weird to sing our kid to sleep with a song about men dying of silicosis, but then again the lyrics to “Rock-a-Bye Baby” are pretty disturbing too. Still, the question of why someone would sing a protest song as if it were a lullaby was very much on my mind during several recent encounters with the work of Scottish artist Susan Philipsz. She has three installations on view right now in Chicago: We Shall Be All and Internationale at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Pledge at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum on the University of Illinois, Chicago campus. The winner of this year’s Turner Prize, Philipsz is widely acclaimed for her use of sound — and more specifically of voice — in works of art that engage the history and culture of protest. Almost all of Philipsz’s installations rely on her own, untrained vocals to weave densely allusive tapestries that commemorate the experiences of those struggling for a better world — something we don’t normally associate with the soothing nature of lullabies.

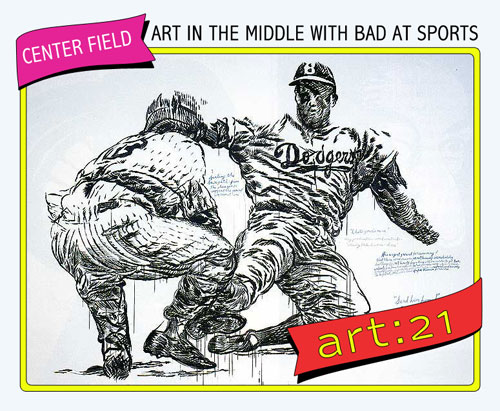

Commissioned by the MCA, Phillipsz’s We Shall Be All references Chicago’s labor movement and its legacy of social reform in the context of worldwide struggles for worker’s rights. I think it’s partly the fact that public-sector labor unions are so much in the news nowadays, due to the efforts of numerous GOP legislators to quash the collective bargaining power of those unions (or even its mere visual representation) that lends such a sharp sting to Philipsz’s Chicago presentations. Consisting of several speakers and a projection screen arranged within a completely darkened room, We Shall Be All takes its title from Melvyn Dubofsky’s We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. This book provides the definitive history of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Chicago-born labor association whose influence was especially strong during the years before World War I. In particular, Philipsz’s piece alludes to the 1886 Haymarket Massacre in Chicago, whose anniversary is commemorated on May 1st of each year in honor of International Workers Rights.

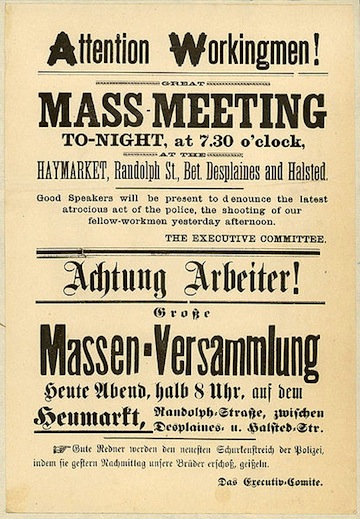

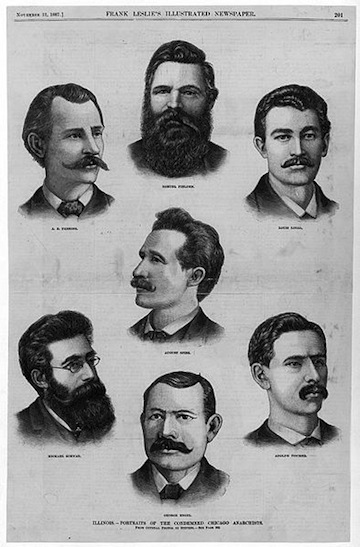

The Haymarket events began as a rally in support of the eight-hour workday but turned unexpectedly violent when, at the end of an otherwise peaceful series of speeches, police ordered the crowd to disperse. A pipe bomb was thrown by an unknown perpetrator, killing police officer Mathias J. Degan. During the ensuing rounds of gunfire, six more officers were shot (many, the Chicago Tribune reported at the time, by friendly fire). In all, eight policemen died and dozens of officers and civilians were wounded. Eight men were subsequently arrested for their roles in the rally, including a newspaper editor turned anarchist activist named Albert Parsons. Parsons and several others were tried and sentenced to death, despite the prosecution’s explicit acknowledgement that none of them had thrown the bomb. As four of the men walked to the gallows on November 11, 1887, witnesses report that they sang the “Marseillaise,” the anthem of both the international revolutionary movement and the French nation.

Significantly, it is not the lyrics to this rousing march that Philipsz sings to commemorate Albert Parsons and other men who died for their cause. Rather, she chose “Annie Laurie,” the Scottish love ballad that, according to lore, was the song sung by Parsons in his jail cell the night before he was hanged. Philipsz’s spare a cappella version is slow and mournful, and is followed by a period of silence. Although no sound is heard, something else is made visible: lines of text. Excerpts from a poem written in honor of Parsons and his comrades by the anarchist poet Voltairine de Cleyre are projected on a black screen:

I am not dead – I am not dead

I live a life intense, divine

Yours be the days forever fled

But all the morrows shall be mine

De Cleyre’s poetic verses echo the words that were reportedly shouted by August Spies in the moments before he was hung alongside Albert Parsons and two other men: “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!”

Philipsz’s silences speak volumes. Through her use of silent moments and lengthy pauses between different “movements,” the truly sculptural nature of her sound work is revealed. Philipsz uses silence as the aural counterpart to negative space – those moments without sound or voice add shade and contour to the space itself, and silence also provides space for us to imagine the inner lives of the people she references.

After silence comes Philipsz’s version of Leonard Cohen’s “Who by Fire,” itself a Midrashic rewriting of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer chanted by Jews during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services. Some say the prayer was composed over 1,000 years ago by Rabbi Amnon of Mainz, Germany, who was martyred after refusing to renounce his faith and convert to Christianity. The Unetaneh Tokef proclaims that in the coming year, some will live and some will die, and calls upon the living to take responsibility for their actions. Cohen’s version adds a haunting last line to the refrain as we realize that the voice of the one who makes this call has become unrecognizable to us:

And who by fire,

who by water,

who in the sunshine,

who in the night time,

who by high ordeal,

who by common trial,

who in your merry merry month of May,

who by very slow decay

and who shall I say is calling?

The fourth segment of Philipsz’s looped piece contains no text or vocals at all; rather, it is an aural evocation of a streetscape excerpted from a four-movement composition titled “East Hastings”– named for a crime and poverty-stricken street in downtown Vancouver—by the Canadian collective Godspeed You! Black Emperor, a group whose own stated anarchist principles in part derive from those that Albert Parsons espoused. In the segment, the lone voice of a street preacher raised prophetically against the prevailing misery of his environment can be heard against the sounds of lilting bagpipes and ambient traffic noise. (Interestingly, a different segment of this same song was also used to set the tone for Danny Boyle’s post-apocalyptic zombie film 28 Days Later).

Godspeed You! Black Emperor; cover of "F♯ A♯ ∞," the album on which the song "East Hastings" appears.

One can imagine that sounds not unlike these could be heard during the bustling heyday of the Hull House settlement in Chicago. It is in the remains of this historic community that Philipsz’s 2003 Pledge is currently installed. Co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, the Hull-House settlement was a community that provided shelter, work, as well as social and educational opportunities for Chicago’s working-class community, including many immigrants from Europe. In its early years, Hull House fostered reformers of all stripes, including feminist activists; indeed, many of the women who lived and worked at Hull House garnered the skills that allowed them to become committed social activists in other cities. The Hull House settlement was sold in 1967 to the University of Illinois. Two of the original buildings, including Adams’ own house, still stand today as a museum commemorating the work of Addams and her colleagues. Philipsz’s piece has been installed in the dining hall, where residents shared food, conversation, and debate. (Art21 artist Louise Bourgeois created a series of sculptures titled Helping Hands for the Hull House; watch a clip of her discussing the work here.)

Pledge consists of Philipsz’s a cappella version of the German revolutionary song “Auf, auf zum Kampf!” (“Up, Up, Let’s Fight”). Instead of approaching this anthem as an upbeat call to action (see, for example, this version), Phillipsz sings it like a lullaby. “Auf, auf zum Kampf!” was often sung in dedication to the martyrdom of Karl Libknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, Marxist revolutionary leaders who were viciously murdered at the hands of German Friekorps in January 1919. Philipsz has in turn dedicated Pledge to the memory of these legendary activists. Luxemburg was bludgeoned by rifle butt and subsequently shot to death in front of the Eden Hotel in Berlin; the distant notes of a piano and the clinking of glasses provides the disconcerting other half of Philipsz’s Pledge, as if contrasting the rousing fight song with the scene of comfortable obliviousness against which Luxemburg’s final moments played out.

So what does it mean to sing a protest song as if it were a lullaby? I like to think that Philipsz is singing not to us, but to those who have been martyred in the name of their cause. Alone in his cell on November 10, 1887, Albert Parsons had no one to hold his hand or comfort him as darkness encroached and the gallows were pounded into life outside his window. So that night, Parsons sang himself to sleep and died a prolonged and painful death by hanging the next morning. So many others have died alone, in tremendous pain and at a stranger’s brutal hands. Perhaps that is why Philipsz’s songs remind me of lullabies. The fact that the world is unjust and human beings suffer is harsh and undeniable. Sometimes, the only comfort to be found is in other human voices, raised in song.