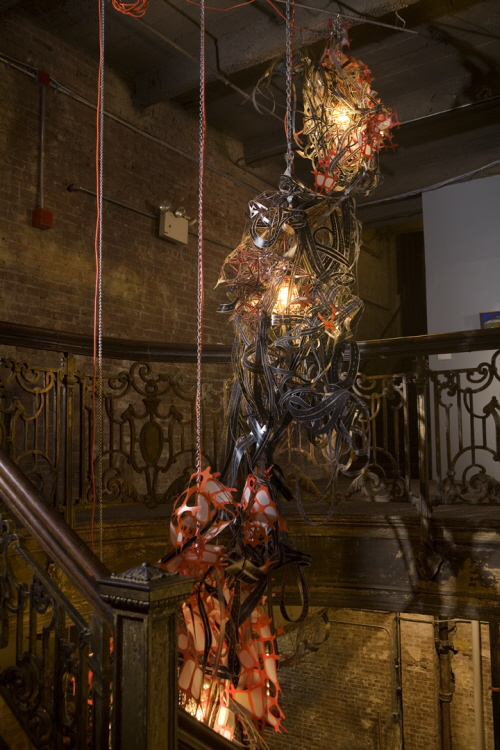

Nicola López, "Closed System," 2009. Installation view, “Next Wave Festival,” Brooklyn Academy of Music, 2009. © Nicola López. Image courtesy the artist.

With the onset of spring, renewal is in the air. In the world of contemporary prints, a fresh format that seems to be popping up everywhere is print-based installation. In recent years, celebrated contemporary artists Swoon, Nicola López, Ryan McGinness, and others have pushed the boundaries of traditional printmaking techniques to create unique works that have the power, presence, and conceptual rigor of work in traditionally associated with “high-brow” media.

Like most new trends in art, printstallation has important precedents. Monumental prints have been created since the Renaissance, primarily to commemorate military victories: Dürer’s Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I (1515-17) and Andreani’s The Triumph of Julius Caesar (after paintings by Mantegna, 1599) are two famed early examples – Jacques Callot also etched a number of oversized battle scenes in the early Seventeenth Century. Yet few artists attempted to work on this scale in prints again until the Postwar period, when Andy Warhol created his famous Cow Wallpaper in 1966 (currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art’s Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building – a later variant in blue and yellow is also on view on the fourth floor mezzanine).

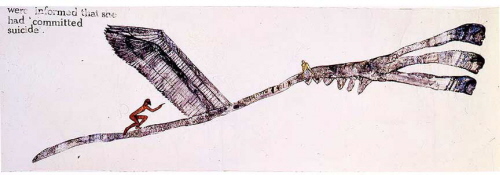

Nancy Spero, "Torture of Women," panel 10 (detail), 1976. Handprinting and typewriter collage on paper, 14 panels totaling 1 2/3 x 125 feet. Photo by David Reynolds. © Nancy Spero, courtesy the artist’s estate and Galerie Lelong, New York.

Over the past four decades, other major artists made headway into using printmaking as a basis for installation, including Robert Rauschenberg, Xu Bing, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Vito Acconci, Peter Halley, and Kiki Smith (some examples can be seen in Deborah Wye, et al. Artists and Prints: Masterworks from the Museum of Modern Art, 2004). However, Nancy Spero (1926-2009) contributed most significantly to the development of the potential of print-based media as a vehicle for installation work. As discussed in Christopher Lyon’s recent critical survey (Nancy Spero: The Work, Prestel, 2010, 186-192), Spero developed her signature large hand-printed works on paper in the early 1970s in response to her struggle with Rheumatoid arthritis. The disease prevented her from painting and drawing on the level she had previously, and she discovered that printmaking media allowed her to continue to work on the scale and production level she desired. Spero eventually developed a lexicon of over 450 stock letterpress plates based on her drawings, which she used in combination with letterpress typeface to create tableaux of interwoven images and text. Though early work was invariably on paper, over time she began to print on other surfaces and incorporate additional materials into her installations. All of Spero’s work is unique and hand-printed – for installations, she mounted the paper on the wall in panoramic or floor-to-ceiling banners. Her uniquely expressionistic and simple figures – which convey pain, mystical power, and monstrosity – are frequently surrounded by text in French, Latin, or English (some borrowed, some of her own creation). Spero combined these elements to expose the cruelty of political oppression, war, and violence against women – subjects to which she was dedicated throughout her career.

Nancy Spero, "The Hours of the Night II," 2001. Handprinting and printed collage on paper, 11 panels approximately 9 x 22 feet overall. Photo by David Reynolds, © Nancy Spero, courtesy the artist’s estate and Galerie Lelong, New York.

Until recently, Spero was the most notable practitioner of print-based installation in contemporary art, but in the past several years, a new generation of artists who work in this format has emerged – many of whom were featured in the Greater New York 2005 exhibition at MoMA’s P.S. 1. Among the most notable are Swoon, Nicola López, and Ryan McGinness, who employ printmaking as a medium for installation works on a scale and complexity that has not been seen before. Though their work is otherwise unrelated, it is interesting to note that these three artists discuss their choice of printmaking media in terms of its direct relationship (as a serial/repeatable medium) to contemporary mass culture and consumerism and – like Spero – work with complex lexicons of their own design.

Swoon began her career as a street artist and, while her work is now also shown in galleries and museums, she remains dedicated to presenting her life-size depictions of individuals in abandoned public spaces. Her primary subject is the people who inhabit this space – from children to street vendors to musicians – engaged in everyday activities. Printed with woodblock and linoleum cut on newsprint or recycled materials (or unique cut-outs of the same paper), Swoon’s portraits are energetic, expressionistic, and deeply human.

Like Spero, Swoon has generated a stockpile of woodblocks and linoleum cuts that she reuses and reconfigures to create new works. Originally, she posted her work in what she calls “third spaces” – walls and surfaces in the public arena that form the urban landscape – in an effort to break out of what she viewed as the lifeless and closed system of high-brow art culture. Instead, she wanted to create art that was participatory and democratic. In her own words, “The minute you put anything on a wall, you’re declaring open season…What I wanted to say is that anyone could do it. We’re telling advertisers, ‘Hey, if you have something to say, that’s fine, but if anyone else has something to say, they can also say it’…It’s about opening the conversation” (interview for The Morning News, September 29, 2004).

Swoon, "Swimming Cities of the Switchback Sea." Installation view (detail), Deitch Studios 4-40 44th Drive, September 7 - October 19, 2008. Photo credit Tod Seelie. Image courtesy Deitch Archive.

In recent years, Swoon has shown work at the now defunct Deitch Projects in New York, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, The Luggage Store (San Francisco), and other museums and galleries across the country. While this represents a departure from her roots in subversive street art, working indoors allows Swoon to create more elaborate installation works that evoke the chaos, complexity, and energy of urban street life. She also continues to post her portraits on the streets, as she did for the contemporary print survey Philagrafika last spring, and has branched into collaborative performance projects that involve building and sailing on boats made of debris. The most infamous of these was The Swimming Cities of Serenissima, 2009, in which she and several others crashed the Venice Biennale by water, performed nightly in the canals, and stormed the Grand Canal at 3:00 a.m.

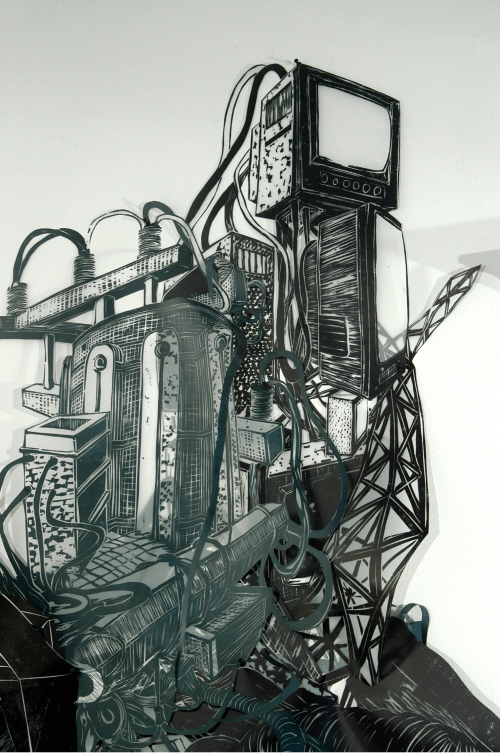

Nicola López has also attracted much critical attention in the past several years for her elaborate print-based installations that creep, flow, swarm, dangle, or explode through space. Tires, roads, wires, tubes, radio towers, safety fencing, electronics, and chemical clouds chart pathways and byways that represent both the analogue and digital aspects of our contemporary obsession with speed, transit, construction, and communication.

Nicola López, "Fallen Giants." Installation view (detail) in "Nicola López / John Copeland," Irvine Contemporary Art, Washington, D.C., June 03, 2005 - July 16, 2005. © Nicola López. Image courtesy the artist.

Though López’s source material is the detritus of the built environment, many of her installations unfold in ironically organic compositions. In Half-Life, no. 5, flower-like forms comprised of machinery spring from a bed of wires, pipes, and fallen towers, seemingly nourished by a fount of mystery liquid spewing from a nearby pipe. Other works are reminiscent of explosions or neurological pathways. Though many interpret her work as dystopian, López takes a more pragmatic view of her work, which she describes as “maps that …. represent how our actual world is structured, not on a literally geographical, but on an experiential level” (artist’s statement).

Nicola López, "Half-Life No. 5," 2007. Lithograph and woodcut on Mylar. © Nicola López. Image courtesy Tandem Press.

Like Spero (whom she cites as an influence), López works with stock images of her own creation that she recycles in various incarnations. In the process of installation, López allows the work to take its own direction. “For me an installation is about setting up the parameters that allow me to go into territory where new things (maybe accidents/risks/chance—and hopefully discovery) will happen.” (Amze Emmons, interview with the artist on Printeresting.org, 2008). In addition to her print-based installations, López also works in drawing and traditional printmaking formats and has recently collaborated with master printers at Pace Prints, Tandem Press, Tamarind Institute, Hui Press, and 10 Grand Press among others. Her work has been shown at MoMA P.S.1, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Chazen Museum of Art (Madison, WI), the Denver Art Museum, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as several galleries throughout the U.S. and Latin America. Marañas, a solo exhibition of Lopez’s work, is currently on view at Arróniz Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City, through May 27.

Ryan McGinness also first came into the public eye in the early aughts with his unique iconography of sleek logo-like forms in garish colors that overlap ad infinitum. This signature style was borne of the realization that “the right kind of logo, the cool logo…can change the value of an otherwise ordinary object.” (interview with Peter Halley in Ryan McGinness Works, Rizzoli, New York, 2009, 9) As a teenager, such products were out of his reach so he began to design his own logos and apply them to skateboards, t-shirts, and surfboards. Soon others wanted to have them, and his career as an artist was born.

McGinness works in a wide range of formats, including painting, sculpture, drawing, and variable editions. Screenprinting is the foundation for a majority of his work, whether on canvas, paper, wood, or walls. His imagery is based on a personal language of signifiers that he combines uniquely for each piece – he is constantly inventing new “logos” and finding ways to reinvent previous ones. McGinness’ installations are generally comprised of paintings presented in a traditional “box” format that are surrounded by oversized icons screened to the wall to create what he calls “total environments… When I’m conceptualizing an exhibition I’m trying to figure out how I can control the entire experience…As a result, the environment/work includes everything down to the bottles of water” (interview with David Byrne, ibid., 34).

Installation view, “Ryan McGinness: Varied Editions,” Pace Prints Chelsea, October 6- Nov. 15, 2007. Image courtesy Pace Prints, New York.

Such an experience greeted visitors to his 2007 exhibition Varied Editions exhibition that debuted the Pace Prints Chelsea location in October of 2007. As explained in the introduction to the chapter in Ryan McGinness Works, he does not “make editions or multiples in the traditional sense.” Instead, he creates basic molds, stencils, or other matrices of his signature logo-like icons that are combined in different patterns and/or color combinations. In addition to traditional fine art techniques, works in the show were created using software, processes, and materials that are commonly associated with industry and mass manufacturing. For instance, for the 2007 Island Universes series, McGinness designed 777 buttons of visual signifiers and pithy phrases like “YOUR LOGO HERE” in three sizes. These were then affixed to blank canvas in shapes also designed by McGinness– the pattern in which they were applied was determined by industrial packing software. Also on view were monoprints created using 72 rubber stamps from the artist’s sketches, and Rainbow McTwist, a multiple comprised of painted and laser-cut skateboards arranged in a radial pattern, edition of 5. Some of the walls were covered with flocked metallic wallpaper of the artist’s design or logos that had been spray-painted on the walls using brass stencils. The buttons used in the Island Universes series were also given away at the after party, at a separate location, which was an installation unto itself.

Buttons given away during "Ryan McGinness: Varied Editions" after party for Pace Prints Chelsea exhibition, October 6- Nov. 15, 2007. Image courtesy Pace Prints, New York.

In addition to these three artists, a number of emerging artists are also working in print-based installation. Rob Swainston’s recent work at BravinLee Programs, David Krut Projects, and Smack Mellon, among others, revealed a strong new voice in this format. His ambition in this format was evident early on in works such as Portapocalypse, an installation he created as a graduate student at Columbia University in 2005. The title refers to both the facture and subject matter of the piece – comprised of easily transported parts that have major wall presence when installed, the work addresses subjects no less weighty than “war, empire, destruction, apocalypse, and the collusion of religion, power, and politics in contemporary American society” (artist’s statement).

Since completing his MFA in 2006, Swainston has steadily forayed into increasingly complex installations, such as Triumphal Arch (an homage to the aforementioned monumental print by Dürer), comprised of stop-animation projected on a woodcut backdrop. Centennial Drift, Swainston’s solo exhibition at BravinLee in early 2010, also featured a woodcut print with projected animation titled Till Tomorrow On. Also at BravinLee was Centennial, a wall installation of 36-inch wide woodcut print scrolls that celebrated the natural grain of the wood. Swainston further developed the idea of a seemingly endless woodcut in his piece In Front of Behind the Wall, an installation of three 24-foot long banners shown earlier this year at Smack Mellon in the exhibition “Site 92: Work Permit Approved.”

Rob Swainston, "In Front of Behind the Wall," woodblock and digital print on paper, three 42in x 24ft scrolls. Image courtesy Smack Mellon. Photo by Etienne Frossard.

There are also a number of installation artists who have recently tried their hand at printmaking to create editions. Among the most notable of these is Matthew Day Jackson. Metamorphosis (2007, Lower East Side Printshop), an installation of six prints with handwork, references various disturbing or apocalyptic events in American history: the Jonestown Massacre, 1978; the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide, 1997; the first test of a nuclear bomb, 1945; and the case of Phineas Gage (a 19th-century railroad foreman who survived an accident in which a metal rod was driven through his head) – a darkened U.S. map underscores the somber mood. Jackson suggests hope in the form of “Lady Liberty” on the far right, a heroic figure representing redemption and renewal. The same year, Jackson has created three additional print projects for his ongoing Dymaxion series in homage to Buckminster Fuller (Peter Blum Edition, 2007), two of which are intended as installation works.

Matthew Day Jackson, “Metamorphosis,” 2007. Seven -part installation: aquatint, etching, screenprint and inkjet print on various papers, felt, and found map with hand additions in Flavor-Aid, colored pencil, and gold leaf. 73 x 154 in. overall. Printed and published by the Lower East Side Printshop, New York. Image courtesy Lower East Side Printshop.

As seen in recent gallery and museum exhibitions across the country, a new crop of contemporary artists are likewise dedicated to, or experimenting with, printmaking media as a basis for installation work (see also last month’s post in this column on IPCNY). If last spring’s contemporary printmaking survey Philagrafika is any indication, it is the next wave for the medium. This fresh approach has been energizing a new audience for prints as well as its longtime dedicatees, and promises great things to come.

Pingback: Ink | Screening Wood: Jessica Stockholder at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum | Your Pure Art