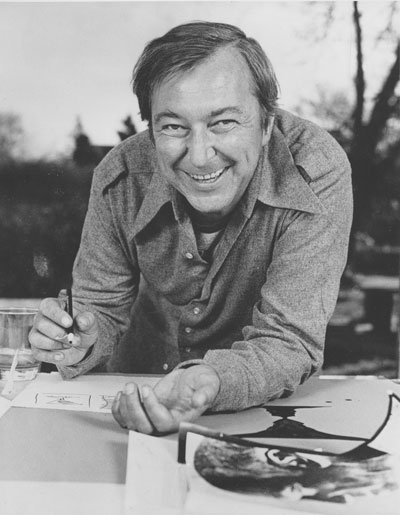

"I am so sorry": Tiger Woods with his wife, children, and two mistresses, Rusty and Mr. Snuffles

Tiger Woods is a profoundly uninteresting man, elevated to role model status in America by his unwavering commitment to brand promotion and the eradication of personal charisma, so when the revelations of his marital infidelities came to light in 2009, it was yet another contradiction of Fitzgerald’s too-quoted line about there being no second acts in American lives. Woods was being given a second chance, to save himself from the ignominy of living and dying the blank-eyed apparatchik of marketing departments at corporations everywhere. He was becoming a human, in the way that all robots in Hollywood films eventually grow a soul. Yet during the televised press conference, Woods’s charmlessness shone through like the sick light of a vandalized lighthouse. “I am truly sorry,” he intoned, auto-AutoTune-ing his voice beyond the wavering reality of the human larynx and by doing so, managed to simultaneously address and obfuscate the reality of his actions. Woods was using language against its function, allowing phrases like “my behavior has been a personal disappointment” to suggest contrition while denying his listeners access to genuine feeling. This is how an institutionalized language works: we’re telling you all we think you need to know. This is how language works in the art world.

“Internet artists come from numerous [sic] backgrounds and the Internet is developing extremely rapidly – these and other factors make it hard to define what makes good Internet art and whether ultimately it will be as durable as other art has been in the past. But if there’s one thing we’ve learned, it’s this: it doesn’t matter. Enjoy!” Thus the institutional voice of one of the world’s most important museums of modern and contemporary art, one funded in part by the public. Tate’s 2009 book How to Survive Modern Art, one of many guidebooks to modern and contemporary art nominally aimed at the general public, is full of examples of the sort of language designed to deny access to expertise. Take this, for example: “Pop artists didn’t try to make their art clever,” or “Pop artists … tried to make art that was as accessible as fast food, television, and pop music.” Both of these quotes come from a page with a reproduction of Jasper Johns’s Target with Four Faces, to give you an idea. Johns (let’s not split hairs, but not actually a Pop artist anyway) couldn’t be accused of not being clever, and despite a guest appearance on The Simpsons, makes work that is probably a bit more complex than, say, Chuck Berry’s “My Ding-a-Ling.” Similarly, complex artistic ideas and movements are reduced to absurdities by the text’s attempts at comprehensiveness. Matisse was an “unusual” artist because “his work was always about happiness.” “Rothko’s aim was to create in viewers a feeling of peace.” Abstract Expressionism was “hard for the public to understand.” Harlem Renaissance paintings were “uplifting and fun.” Art made before modernism was about “royalty, the nobility or members of the clergy looking down on the rest of us.” All of it.

Jasper Johns: not trying to be clever

Art is the most self-exegetical of cultural products. There are countless publications like the ones above, each one aiming to provide a loosely defined public with a breezy overview of the history of modern and contemporary art. Almost universally, these guides feature, as the Tate’s book does, little floating boxes of text that instruct you how to look at an abstract painting (say) in the vaguely authoritative terms of a relaxation tape (“Look at each work, relax, don’t talk and try not to think of anything in particular”). Imagine such a book being made about music or film or fashion, and it’s striking how consistent art is in trying to explain itself. People who work around and make art are often insecure about the frivolity of the enterprise (see Dave Hickey’s essay “Frivolity and Unction” for a defense of this) and invented a technical language designed to evoke — though not embody — philosophical, political, and social importance. But what’s perhaps more insidious and worrying isn’t the syntactic gymnastics of the press release but the institutional voice and its deferral of public access to expertise. A defense of a book like How to Survive Modern Art will trumpet its “accessibility” to the general public, but in reality it does the opposite, slamming the doors of the academic inner sanctum with a casual excuse about Matisse’s works being all happy and lighthearted while ignoring the fact that very many of them are the exact opposite. What this shutting-out implies is that the public won’t understand Matisse beyond pretty colors and lounging Mediterranean babes; what it hides is an insecurity about the value of hard-won academic credentials. It claims ownership over the past, asserting academic over lived expertise, raising the question asked by John Berger in Ways of Seeing:

To whom does the meaning of the art of the past properly belong? To those who can apply it to their own lives, or to a cultural hierarchy of relic specialists?

When Tiger Woods stepped down from the podium to embrace his mother, having promised to embark upon a self-mortificatory program of (what else?) therapy, there must have been a moment when he believed he’d actually managed to persuade the world that he was genuinely contrite. (Whether or not he was isn’t the question.) Obviously, it was the Judeo-Christian symbolism of the act itself that mattered, not Woods’s Schwarzeneggerian erudition, and yet Woods’s speech spoke profoundly of the contemporary relationship between public discourse and historical truth. This has real significance for the way in which institutions like museums provide access points for the public. An institutional voice that blocks, obscures, and brushes over the truth is a voice that implies a separation in levels of understanding between the institution and the visitor. “You either get it or you don’t,” says the Tate text, in reference to a Donald Judd stack. We get it and you won’t, is the implication, proving Kurt Vonnegut’s almost-instinct almost true: modern art is a conspiracy between artists and rich people to make poor people look stupid. It isn’t, of course, but you’d never know it.

Kurt Vonnegut

Pingback: Weekend Links: Diminished Worlds | Stephanie Vegh

Pingback: criticismism » Blog Archive » Found Objects 30/04/2011