William Leavitt, "Spectral Analysis," 1977/2010, set for performance . Photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy the artist and MOCA.

As I was walking through William Leavitt: Theater Objects, the LA-based artist’s first museum retrospective, a MOCA security guard stopped me.

“Are you a writer?”

It took me a moment to register the question. “I write about art sometimes.”

He looked pleased. “I noticed you writing a lot in that notebook, taking notes.”

“I think I’m going to write about this show.”

He appeared even more pleased. “You should write about the security guard. Say ‘the security guard was really nice.’” We both laughed, and I agreed to his request.

The security guard was really nice. He didn’t even tell me to stop using my pen, and force me to switch to a stubby MOCA pencil (I had that much more standard conversation with another museum guard in a different part of the exhibit a few minutes later).

I wanted to present our dialogue partially to keep my word. But the temporary breakdown in boundaries between us seemed like such an anomaly, that I was immediately inclined to believe the interaction was a response to Leavitt’s work. We were standing next to Cutaway View, which, like Leavitt’s other installations, is a decontextualized domestic interior–essentially a stage set–with walls that are actually theater flats, propped up by exposed lumber. A potted plant rests in the corner, and an unremarkable painting framed horse painting hangs on the gray wall.

Installation view of "William Leavitt: Theater Objects," March 13-July3, 2011, MOCA Grand Avenue, photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy MOCA.

On the backside of the wall, Leavitt has crafted a short fictional narrative about the history of the horse painting tied to racing, the mafia, and interpersonal melodrama. In an interview published by Mousse, Leavitt describes the text as “kind of a joke about Hollywood backstories”—a pun since “it’s literally on the back of the set.”

Yet even when Leavitt gives us a backstory, it aches to be completed. Leavitt provides artificial scenery, props, and lighting and demands that the viewer activate the space. It felt as though the guard and I were animated by the Leavitt’s piece. The guard broke out of his normal role and implicated himself as an active participant. It is especially significant that he turned the attention in on himself. He was standing on a stage set, and he wanted to be seen, and moreover, documented.

William Leavitt, "California Patio," 1972. Mixed media (artificial plants, Malibu lights, flagstone, slider, curtains, wooden wall, and text), 96 x 144 x 96 in. (243.8 x 365.8 x 243.8 cm), Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Courtesy MOCA.

Leavitt told the LA Times, “I’m trying to frame some story through an object or a painting or a situation that would lend itself to further narrative.” While Leavitt often writes and stages performances, plays, stories, and readings, the sets mainly function as sites of possibility and projection. They are doubly uncanny meta-stages—theater sets representing theater sets that represent reality.

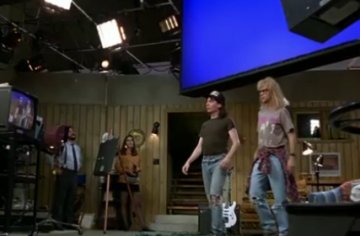

Leavitt’s work evokes that peculiar déjà vu-esque spookiness infamously summed up by Wayne’s World’s Garth Algar. After signing their public access show over to a big network, Wayne and Garth stare at the high budget reconstructed version of the duo’s original set. “I mean, we’re looking down on Wayne’s basement. Only, that’s not Wayne’s basement.” Wayne subsequently identifies Garth’s statement as a haiku–which is especially appropriate given the genre’s association with finding profundity in ordinary moments.

Screen capture from "Wayne's World." Courtesy MovieClips.com

In fact, part of Leavitt’s genius is his ability to create installations and images that seem entirely generic. California Patio, as the title suggests, epitomizes the post-war tract home patio, with its sliding glass doors, flagstone ground, and standard garden foliage. Although Leavitt includes elements that are particular to Los Angeles scenery, they retain a neutral quality. Perhaps images LA have been reproduced so many times that they now feel familiar to almost anyone in our culture. Or maybe LA, which often resembles a vast sprawling suburb rather than a true city, encapsulates all the archetypical elements of the American Dream.

Installation view of "William Leavitt: Theater Objects," March 13-July3, 2011, MOCA Grand Avenue, photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy MOCA.

Like his ersatz theater sets, Leavitt’s paintings operate as paradoxically distinctive and familiar. Even his technique feels pointedly mundane, as his easel-sized works hover in the nondescript spectrum between virtuosity and expressionism. Leavitt is gifted in focusing his eye on scenes and structures that epitomize modern LA architecture—big glass walls, futuristic boxy forms, and precarious hillside engineering. At the turn of the twenty-first century, Leavitt picks up where the post-industrialization Parisian flâneur predecessors left off a hundred years ago. Los Angeles (in some sense Paris’s successor as the world’s epicenter of culture production and tastemaking—however low-brow that taste may be) is comprised of expansive domestic spheres, rather than bustling urban sidewalks. Though our landscape is dominated by private space, most of it is quite visible behind slender, dwarfed succulents, palms, and cacti.

Still, his visions of gardens, carports, and bridges are hauntingly devoid of human subjects. And not in the manner in which traditional plein-air painting omits the figure. As with the installations, his paintings hang like unfinished stories. No palpable action occurs, but within that nothingness lurks tension and possibility—and the imagination of the viewer.

William Leavitt, "Twin Banana Palms," 1998. Courtesy aisforartform.tumblr