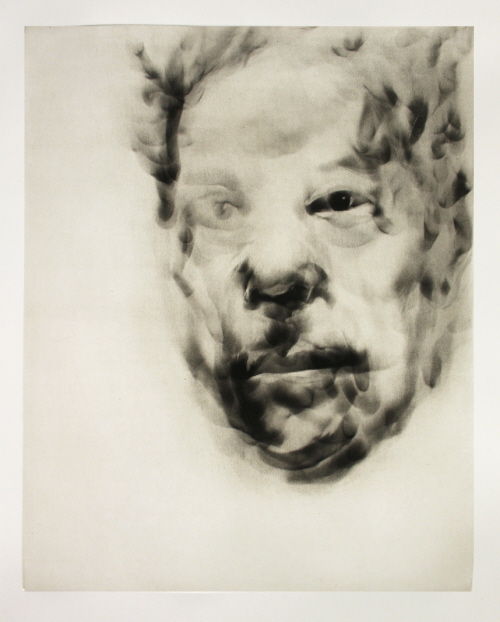

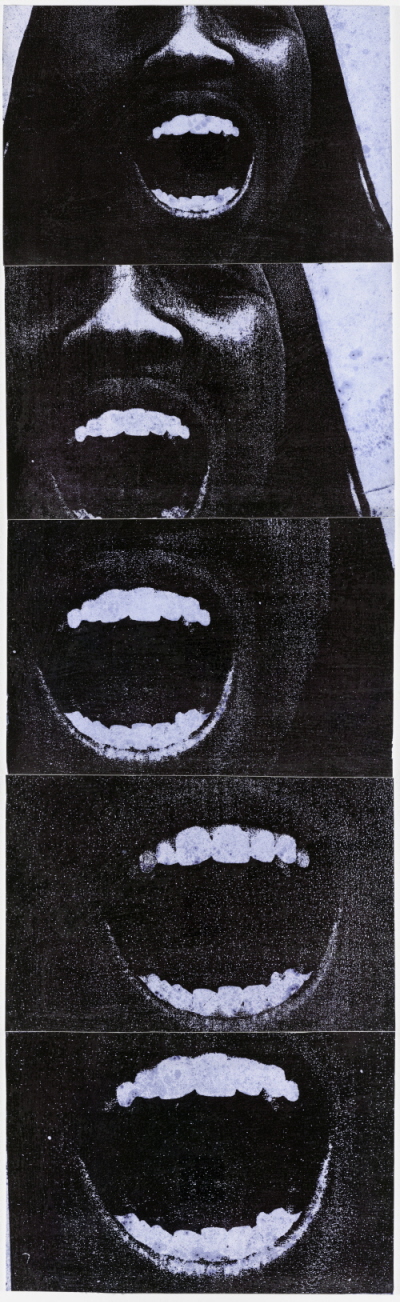

Diane Victor (South African, born 1964), “Fading Man I,” 2010. Intaglio. Plate: 20”x16”. Publisher and printer: Center for Contemporary Printmaking, Norwalk, CT. Edition 25. Courtesy Center for Contemporary Printmaking. © 2011 Diane Victor.

As interest in William Kentridge’s work has grown over the past decade, so has interest in South African art as a whole. Printmaking is a central component of the cultural landscape in this country and it is an important form of expression for many of its artists. In general, South African printmaking is characterized by political and emotional honesty and a refreshing fidelity to the technical roots of the medium. Kentridge, of course, is a prolific printmaker (see the November 2010 post of this column), as are Conrad Botes, Norman Catherine, Robert Hodgins, Anton Kannemeyer, Cameron Platter, Claudette Schreuders, Diane Victor, and Ernestine White, to name a few. The work of these and other artists, who are well known in their homeland, have begun to garner increased attention in the U.S. recently, appearing in art fairs and featured in solo exhibitions at major galleries and museums.

Several exhibitions this year have introduced a wider American audience to the vital printmaking scene in South Africa. Most visible and comprehensive among these is Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now, a group exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art on view through August 14. Earlier this spring, Boston University hosted dual exhibitions in honor of the 25th anniversary of Caversham Press, the first professional printmaking workshop in South Africa. At the same time, the Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College, Grinnell, Iowa, launched the first major solo exhibition of Diane Victor’s work in this country – an auspicious introduction to this important artist who is becoming better known to an international audience. In March and early April, David Krut Projects mounted “Contemporary South African Prints: DKW and I-Jusi,” a retrospective of I-Jusi magazine (an underground art ‘zine dedicated to South African identity and politics, founded in 1994), and David Krut Workshop, a professional printmaking studio established in Johannesburg in 2002. Later this fall, Jack Shainman Gallery will host a solo exhibition of Anton Kannemeyer’s work.

The MoMA exhibition now on view provides “a representative, quality cross-section of contemporary printmaking activities in South Africa over the last five decades,” as described by exhibition curator Judith Hecker, Assistant Curator in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books in a recent e-mail interview with the author. Drawn from the museum’s collection, the exhibition and accompanying catalogue provide critical insight to role of printmaking in South African culture and politics, presented in terms of the country’s recent massive political changes from an apartheid-ruled state to an evolving democracy. In addition to a scholarly essay by Hecker, the accompanying catalogue provides further information and bibliographic citations on each of the artists, collectives, organizations, and workshops represented. It also includes contextualizing photographs and a timeline of printmaking, cultural, and political events.

The exhibition was inspired by Hecker’s previous work with William Kentridge’s prints (she contributed to the recent traveling exhibition William Kentridge: Five Themes and authored a related publication titled William Kentridge: Trace; Prints from the Museum of Modern Art) and prompted by a curatorial initiative to “expand the museum’s holdings to better represent the breadth of printmaking activities in South Africa” (Hecker in a recent e-mail interview with the author). The first South African artist to enter the print collection was Azaria Mbatha in 1967 but he was the sole representative until the department began to acquire Kentridge’s work in earnest in the 1990s. Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now (and the museum’s holdings) were developed over a period of six years; in preparation, Hecker traveled to South Africa for extended periods in 2004 and 2007. As noted in her introduction, this is not the first scholarly examination of the topic (preceded by Printmaking in a Transforming South Africa, 1997, and Rorke’s Drift: Empowering Prints; Twenty Years of Printmaking in South Africa, 2004, both by Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin). However, it is the first to be made widely available to a U.S. and international audience, by virtue of MoMA’s visitorship and following.

The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are divided into five categories, four of which are technique-based – the final category, Postapartheid: New Directions, shows the openness and experimentation that characterizes recent print production. Due to the nature of the exhibition, artists are generally represented by only one or a handful of works – therefore, it is best understood as a starting point for exploration. In Hecker’s words, “The show, and our holdings, do not aim to be complete or definitive… it reflects a work in progress; we plan to continue to acquire works by South African artists” (e-mail interview).

The first section focuses on the favored status of linocut amongst South African artists, a tradition that began during apartheid. As discussed by Hecker, its ease of use, affordability, and accessibility made it a natural choice for the community workshops and non-profit art schools that served black artists, who were attracted to its stark graphic power. Early practitioners included Azaria Mbatha, John Muafangejo, Dan Rkogoathe, and Charles Nkosi, many of whom were involved in the Black Consciousness Movement founded by Steve Biko. Their work centered around “themes of ancestry, religion, and liberation” (Hecker, Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now [New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2011], 12).

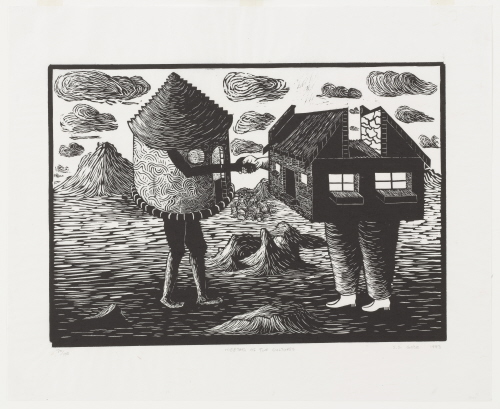

In the early 1990s, the country moved through intense political protest and international political pressure into a peaceable – though contentious – conversion to a democratic nation. Meeting of Two Cultures (1993), a linocut by Sandile Goje, summarizes the spirit of reconciliation that characterized this period. The image shows two biomorphic homes shaking hands: the structure on the left is in the style of the Xhosa people (who were the original inhabitants of the area), at right is a home characteristic of the European ruling class. The linocut section of the exhibition also includes recent prints of stunning technical achievement by William Kentridge, Vuyile C. Voyiya, Cameron Platter, and others. These are less intensely political in their subject matter, though still grounded in the recent history of the nation.

Sandile Goje (South African, born 1972), “Meeting of Two Cultures,” 1993. Linoleum cut. Block: 13 3/4 × 19 5/8" (35 × 49.8 cm). Publisher and printer: the artist, Grahamstown, South Africa. Edition: 100. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Ralph E. Shikes Fund. © 2011 Sandile Goje.

The second area of the exhibition examines the role of posters in mobilizing the citizenry during the peak years of anti-apartheid protest in the 1980s. Underground organizations such as Medu Art Ensemble (formed by exiles in Botswana), United Democratic Front, Save the Press Campaign, and Gardens Media Project produced bold printed materials in response to harsh legislation enacted by the government that were posted or distributed in the streets.

Installation view of "Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now" at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Poster work (1980-1989) by various South African organizations and artists. Photo by Jason Mandella.

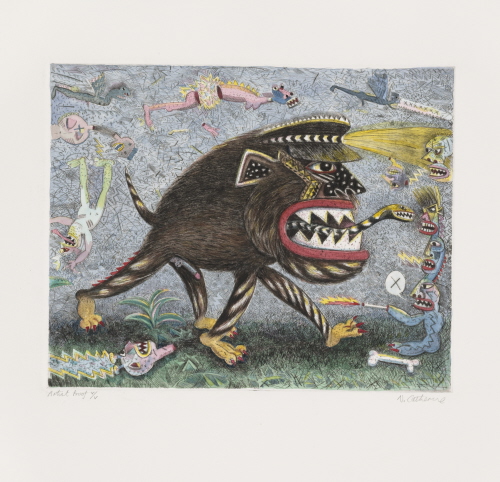

Intaglio prints comprise the third section of the exhibition. A technically challenging process, the equipment and training necessary for intaglio printing usually necessitates collaboration with a master printer. Caversham Press (now Caversham Centre), founded in 1985 by Malcolm Christian, was the country’s first professional printmaking workshop to provide this service. Robert Hodgins, Deborah Bell, Norman Catherine, Mmapula Mmakgoba Helen Sebidi, and William Kentridge were among the first to be invited to work at Caversham Press. The nation was embroiled in deep political strife at the time and the situation was reflected in a majority of the work produced. Norman Catherine’s Witch Hunt, a hand-colored drypoint from 1988, captures the intense and violent presence of military forces in the streets.

Norman Catherine (South African, born 1949), “Witch Hunt,” 1988. One from a series of six drypoints with watercolor additions. Plate: 9 13/16 × 12 3/16" (25 × 31 cm). Publisher: the artist, Hartbeespoort, South Africa. Printer: Caversham Press, Balgowan, South Africa. Edition: hand-colored artist’s proof before the edition of 25. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Virginia Cowles Schroth Fund. © 2011 Norman Catherine.

In the early 1990s, Caversham changed its name and expanded its mission to provide training and resources to emerging artists and the community. (A dual retrospective and group exhibition of work produced at Caversham over the past 25 years was hosted earlier this year by Boston University College of Fine Arts.) Caversham was joined by several other professional presses over the following decade – including The Artists’ Press, White River; Hard Ground Printmakers Workshop; David Krut Workshop; and Fine Line Press, Rhodes University – making the techniques of intaglio and lithography more available to artists in South Africa.

Also on view in this section are a selection of eight prints by Diane Victor, who has recently garnered well-deserved international attention for her exquisite allegorical intaglios and drawings that mine the psychological ramifications of the nation’s history of apartheid. The works on view at MoMA are from her ongoing Disasters of Peace series. Like Goya’s famed Disasters of War series, upon which they are based, this ongoing series of prints calls attention to human atrocities in an allegorical format.

Diane Victor (South African, born 1964), "5000 Rand a Head" (2001) from the series "Disasters of Peace," 2001–present. One from a portfolio of sixteen etching, aquatint, and drypoints with roulette, plate: 8 7/16 × 11 9/16" (21.5 × 29.3 cm). Publisher and printer: the artist, Pretoria. Edition: 25. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Ralph E. Shikes Fund. © 2011 Diane Victor.

Earlier this year, Victor was the subject of a major solo exhibition at the Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College, Grinnell, Iowa – her first at a larger educational institution in the U.S., following her first solo show at David Krut Projects in Fall 2010. (Grinnell College also played an important role in promoting Kentridge’s graphic work in this country.) The exhibition, Of Fables and Folly: Diane Victor, Recent Work, curated by Kay Wilson, covered the past ten years of the artist’s production and featured several intaglio prints, including the Disasters of Peace and Birth of a Nation series, as well as a number of drawings, some of which were created specifically for this installation. Birth of a Nation, a series of ten drypoints completed last year, is an extended allegorical commentary on the legacy of colonial power in South Africa (additional images and further discussion available on the David Krut Projects website). The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue (downloadable pdf here) with an essay by Jacki McInnes, a South African artist, curator, and writer, who astutely discusses Victor’s “searing, uncompromising, and unremitting response” to the severe inequities that are still apparent in her native land.

Diane Victor (South African, born 1964), “Romulus and Remus,” 2009. From “Birth of a Nation” series. Drypoint. 14.65 x 18.7 inches. Publisher and Printer: David Krut Projects, New York and Johannesburg. Edition of 40. Courtesy of David Krut Projects, New York.

As seen in the Grinnell exhibition, Victor’s has developed two signature drawing techniques that produce haunting effects in service to her artistic vision. Victor’s “stain drawings,” in which she applies controlled areas of charcoal staining to drawn figures, either evoke the fragility of the body or the corruption of power, depending upon Victor’s intention. Likewise, the fluidity of her “smoke portraits,” which she produces through manipulation of the carbon by-product of a burning candle, convey a startling and ghostly humanity to the native peoples of South Africa that are her subject (many of whom are prisoners awaiting trial). This technique is extremely delicate and can be destroyed with the slightest contact – a parallel to the transience of human life and individual destiny that she finds particularly satisfying (images are available on the David Krut projects website). In September of 2010, Victor completed a residency at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in Norwalk, Connecticut, where she was able to translate her smoke drawing technique into intaglio form for the first time with the assistance of Master Printer Anthony Kirk (one example pictured at top). She also completed three drypoints there that are currently in the process of being editioned.

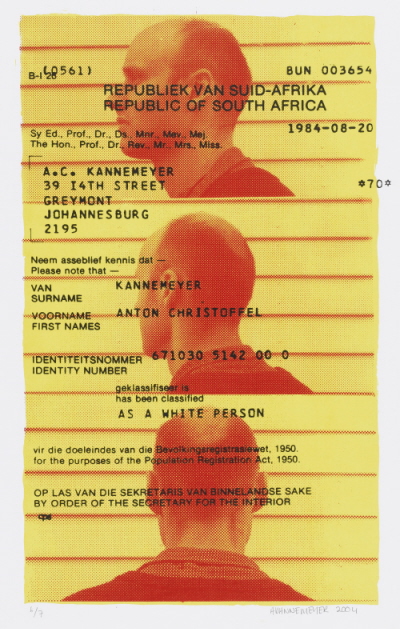

Returning to the exhibition at MoMA, the intaglio section is followed by an area devoted to the use of photographic source material in prints. The works on view demonstrate a range of approaches, from straightforward documentary to manipulated imagery, most of which address social and political issues. To create For Thirty Years Next to His Heart, 1990, Sue Williamson scanned each page of an individual’s passbook — an “icon of apartheid,” (Williamson as quoted in Hecker, 17) that served as an identification document similar to a visa. Non-white citizens were required to carry one at all times and present it to officials upon request; records of employment and location changes were inscribed within. Passbook laws were repealed in 1986, but the owner of this example continued to carry his for several years, out of habit and as a measure of imagined security. Nearby, Anton Kannemeyer’s A White Person, 2004, shows the flip side of these regulations – in this work, the artist enlarged the simple identification card that confirmed his status as a white person (who was therefore free to come and go as he pleased), superimposed over three photographs of his head at different angles that resemble mug shots.

Anton Kannemeyer (South African, born 1967), “A White Person,” 2004. Screenprint. Composition: 22 3/16 × 13 11/16" (56.3 × 34.8 cm). Publisher and printer: the artist, Stellenbosch, South Africa. Edition: 7. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Susan and Arthur Fleischer, Jr. © 2011 Anton Kannemeyer.

The closing section of the MoMA exhibition is dedicated to new directions in printmaking by South African artists. As the political climate has cooled somewhat, so has the intensity of political expression in art. Though some artists remain overtly grounded in political issues and critiques of government, others refer to the nation’s past and present obliquely, or not at all. Bitterkomix, an underground art comic founded in 1992 by Corad Botes (a.k.a Konradski) and Anton Kannemeyer (a.k.a. Joe Dog), employs the graphic novel form to satirize various aspects of South African government and culture. (Bitterkomix 14 and Bitterkomix 15 can be previewed on Google books – please note that some strips are in Afrikaans and/or contain explicit material). Cameron Platter — who works in sculpture, film, and digital printmaking – combines traditional South African cultural influences (including folklore, linocut, and woodcarving) with the visual language of street life to create playfully provocative commentary on contemporary life in his homeland. Ernestine White – a printmaker and curator who lived in the United States from ages 11 to 26 and trained at the Tamarind Institute in New Mexico (see the October 2010 post for this column) –explores issues of identity and belonging in her experimental prints, some of which are presented in wall installations; recent work has focused on child abuse and children’s rights issues. In contrast to the above artists, sculptor and printmaker Claudette Schreuders creates doll-like figures that seem to be involved in quiet dramas of a personal nature. Though traditional African art is an occasional referent in her work, the focus is on creating psychologically suggestive scenes. Likewise, Paul Edmunds works in a minimalist and formal vein that is quite removed from the harsh political and social history of South Africa, though it is grounded in the material culture of his country.

As seen in recent museum and gallery exhibitions, international and American art audiences are eager for a deeper exploration and understanding of the prodigious printmaking activity in South Africa over the past several decades. From traditional linocuts to contemporary digital satire, the universe of South African prints provides a wealth of compelling work for the curious. The proliferation of print workshops and professional training schools ensure a rich and varied future for print production in South Africa, which will surely continue to evolve as the nation matures and settles into its status as a free nation.

Ernestine White (South African, born 1976), “Outlet,” 2010. Photocopy with lithographic ink on five sheets. Overall: 53 15/16×15 15/16" (137 × 40.5 cm). Publisher: unpublished. Printer: the artist, Cape Town. Edition: 2 unique variants (in 2005 and 2010). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. General Print Fund. © 2011 Ernestine White.