A small black and white newspaper photograph hangs on the wall of Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s studio, located in an old warehouse in Istanbul’s Karaköy district. The photograph is crowd shot, taken from above, and thus mostly of the tops of people’s heads. It is from the 9th Istanbul Biennial, in 2005. “That’s me,” she says, pointing to one of the tiny figures in the crowd. The Biennial was the first large-scale “art event” that Çavuşoğlu had ever attended, and she points to this moment as the point at which she realized she wanted to be an artist, to be a part of the community represented by the Biennial. Though she had completed her BFA in Cinema and Television at Istanbul’s Marmara University the year before and had already completed one of her earliest works, Dominance of Shadow (a project in which the poster for a made-up film was posted on rented billboards throughout Istanbul) and even participated in a group show at Platform Garanti titled That from a long way off looks like flies, she was not yet working full-time as an artist or even thinking of herself as such. Attending the Biennial changed all that.

In the nearly six years that have passed since this turning point, Çavuşoğlu has pursued her career at a breakneck pace, establishing herself as one of the most intellectually stimulating and active members of a new generation of young Istanbul-based artists, most of whom were born either in the years leading up to or directly following the 1980 military coup. Though they work in a variety of styles and media, these young artists, much like the generation of Turkish artists that proceeds them, all have at least one foot planted firmly in the field of conceptual art and continue to explore questions located at the intersection of art, everyday life, and politics in the tradition of artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Joseph Beuys, and the Paris-based, Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis. While rooted firmly in the political realities (and surrealities) of life in Turkey, the many opportunities, made available to them at the early stages of their development, to participate in residencies and exhibitions throughout Europe, the Middle East, and other parts of the world, has enabled this generation to consider the conflicts and contradictions that characterize their locally specific experience through a broader lens that connects the local to the global flow of capital, labor, bodies, information, and ideas.

At the time of our meeting in early February, Çavuşoğlu had recently returned to Istanbul from Cambridge, UK, where she completed a performance titled I have built my case on the evidence that vaporized before your eyes at the Wysing Arts Centre. This past summer she spent three months in residency at the Centre’s International Camp for Improbable Thinking, during which she worked on the initial development of a film project that will form the core of her next solo exhibition, scheduled to take place at Künstlerhaus Stuttgart in Stuttgart, Germany next year. Like many of Çavuşoğlu’s works, the film deals in large part with the experience, process, and psychological consequences of modernization: the feeling of being “lost,” of getting stuck in the transition and never feeling completely at ease with oneself or within one’s socio-cultural context. “I’m interested in this moment where a many people feel themselves to be in a crowded space, where they can’t relate themselves to either East or West and they don’t know where to stand. There are a lot of thinkers and poets and philosophers who mention in their writing how they feel that they can’t stand where they want to.”

By delving into this moment of transition, Çavuşoğlu hopes to better understand the sense of alienation that she feels she has inherited from her predecessors. As part of the modernization film project, she is simultaneously designing objects and sculptures that will be used in the film and displayed alongside it in the Stuttgart exhibition. One such sculpture is a piece she is developing in collaboration with renowned architect Emre Arolat, inspired by séances conducted by the Turkish spiritualist Bedri Ruhselman in the 1940s and 1950s. During these séances, Ruhselman would converse with restless spirits about their experiences in the afterlife; according to Çavuşoğlu, “he described the other world as being very similar to the Turkish modernization process,” using the language of progress and self-improvement to explain their situation. In Ruhselman’s account of the afterlife, spirits lived in tall, skyscraper-like buildings, an image that Çavuşoğlu and Arolat are using as the point of departure of their architectural collaboration.

Historical material provides a key source of inspiration for Çavuşoğlu’s work, and the research phase is an important stage in her creative process. She talks about the “complex situation” she experiences when she goes to the library to conduct research and is unable to read any documents that predate 1928 because they are written in Ottoman Turkish. As part of Atatürk’s cultural reforms that transformed Turkish society immediately following the founding of the Republic, the Turkish language was completely overhauled and its Arabic script was replaced with Latin characters. Thus in order to gain access to the information these documents contain, they must first be translated for her. The inability to read the original documents pertaining to her national history creates a sense of being lost to one’s own history. This experience is just one example of the hundreds of disjointed moments that add up to a pervasive sense of alienation from one’s own self, an alienation whose heritage Çavuşoğlu is currently exploring.

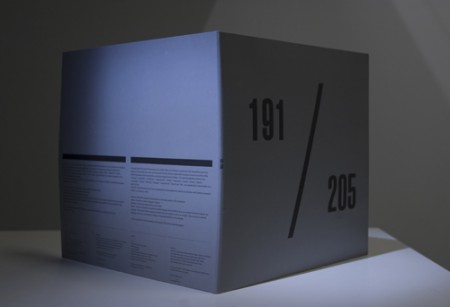

“There is this fact that Turkish history lacks archives, [and thus] it’s very easy to construct knowledge,” she explains. “You can reproduce documents, and you can also reproduce the history, how it functions after the Turkish Republic was founded. After the Republic was founded, the politicians decided to deny the part of our having been the Ottoman empire. So they recreated the history, because there were no documents, nothing.” By appropriating the very technique used by early Republican politicians to rewrite the nation’s history, Çavuşoğlu’s crafted history undermines their project of erasure. For example, in her 2009 project titled 191/205, she collaborated with a Turkish emcee, MC Fuat, to create a recording of 191 of the 205 words that the Turkish government banned from being uttered in television or radio broadcasts “on the grounds that they do not comply with the general structure and operation of the Turkish language and that they are beneath the level of standard Turkish.” Such words included the Turkish words for “revolution,” “nature”, “dream,” “theory,” “possibility”, and “history.” Read aloud, one after another, these 191 words form a seven minute long track that Çavuşoğlu recorded as a 12″ LP record. Though the ban on these words was eventually repealed, 191/205 serves as a reminder and record of that moment of censorship. At the same time, it fills the void that the ban, albeit temporarily, created in the Turkish public’s lives.

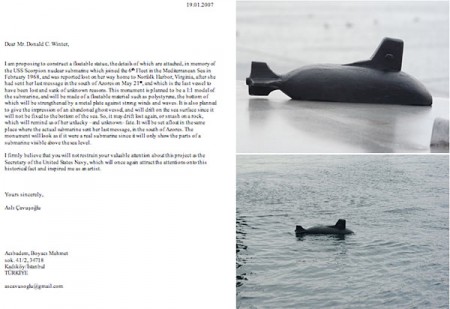

With such projects, Çavuşoğlu demonstrates the basic truth that what we know as “history” is often the the result of largely subjective processes, and an artist’s version of history, whether rendered as an object, book, film, or document, can be just as true or untrue as that created by historians–or, depending on the country and moment in time, politicians masquarading as historians. This understanding of the malleable nature of history lies at the core of Çavuşoğlu’s practice. Projects such as the “Monument Proposals” series, in which she sent proposals to the governments of several countries for national monuments that she knew full well would never be accepted–such as a proposal to the U.S. Navy to create a monument to the USS Scorpion, a nuclear submarine which was lost at sea in 1968 due to mechanical failure–test the limits of memory and representation when it comes to issues of national memory. At the same time, projects such as The Petty Travel Show For a Dear Audience, in which Çavuşoğlu created a nine minute, forty second video from many hours of footage recorded by her aunt and uncle of their tourist trips around the world, are more concerned with historiography on the micro level, the creation of personal rather than national histories.

“I can’t say that all my projects are related to Turkey or the situation here,” she says. “But of course, if you are from this country there are some–many–things you feel like you need to deal with.” However, while she finds living in Istanbul stimulating, it’s also sometimes exhausting for her. “I like being involved in what’s happening here and being engaged, being involved in demonstrations,” she says. “But sometimes it’s too much. I’m not saying it’s bad… But it’s not a nice feeling to feel sick everyday after reading the newspapers.”