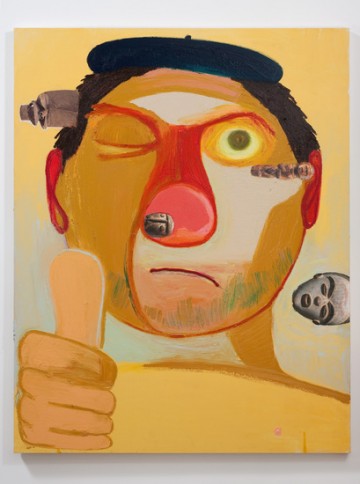

Nicole Eisenman, "Guy Artist," 2011. Oil and collage on canvas, 76x60 inches. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Digging through Nicole Eisenman’s current show at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, one begins to understand why it’s so perfect that the artist presents us with 77 different titles for the show. And by the way, if you need to liven up your day, I strongly encourage you to read the entire list, found at the bottom of the press release, as they bounce from goofy (I Love K-Fed) to satirical and heavy (For My Dead Father). Likewise, the show bubbles with humor and satire, while consistently driving at big questions. Facing the entryway are three tall portraits, titled Guy Racer, Guy Artist, and Guy Capitalist. Breathing fluidly in Vielmetter’s large gallery, the portraits are comical but at the same time impossibly lonely. The mammoth scale of the faces and viscerally gloppy swaths of paint easily envelope each viewer, and the bulging cartoon eyes on each face feel at once attentive and detached. Guy Artist squints one eye and holds up his thumb, in the classic figure drawing maneuver of sighting, while the capitalist’s assemblaged coin-eyes remain vacant. Collaged photos of African masks float sideways across the series, dwarfed by the pale Guy faces; embedded allusions to Primitivism, Cubism, and perhaps beyond art history.

Indeed Eisenman’s masterful paint handling channels an incredible range of artists, from Goya to Picasso. Yet Eisenman’s voice is entirely distinctive, buoyed by her art historical influences, rather than tethered by them.

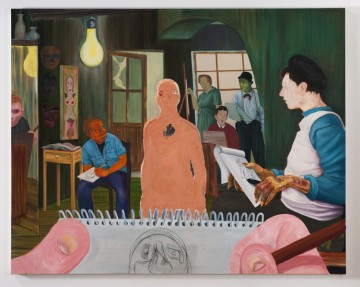

Nicole Eisenman, "The Drawing Class," 2011. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 82" x 65". Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

In the next room, Eisenman playful inserts the viewer into various scenes. Assigning us grotesque giant hands, we are thrust into Séance and The Drawing Class. Eisenman’s brushwork is at once lush and flat, and in this way she often conjures Philip Guston and here, she includes his trademark naked light bulb dangling above the seen of the art classroom, reflected again in the mirror. Tea Party, which features a woman dozing while cradling a rifle, Uncle Sam, and two other figures huddled at a table assembling dynamite, is perhaps Eisenman’s most overtly political work and at the same time one of her most emotive pieces.

Eisenman’s group scenes give ways to romantic pairings in the third room, as she invokes Rodin and Brancusi in three repeated images of two faces fusing together in a kiss. The paintings, Yellow Beach Kiss, Springtime Kiss, and Garden which circle back to a piece in the first room, Sloppy Bar Room Kiss. Eisenman truly shines when she turns her eye and hand to interiors, and the latter painting shows two floppy figures melting into each other and most of all melting onto a table, surrounded by bottles while other patrons ignore them in the distance. But the kiss series in the third room moves from Eisenman’s characteristic bold colors and toothpaste-thick swaths into a romantic, Rococo pastel palette, with thin watery smudging into form à la Odilon Redon.

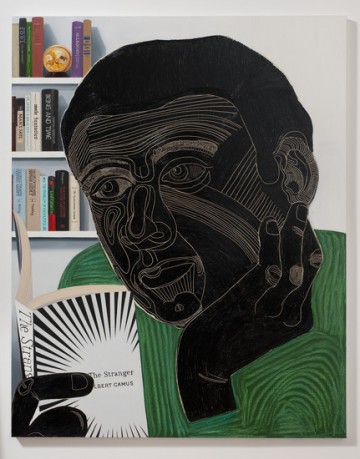

Nicole Eisenman, "Guy Reading The Stranger," 2011, 76" x 60." Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Of course these over-the-top Romantic gestures are tempered by Guy Reading the Stranger – another mammoth portrait, but with wrinkles and features carved with looping sgraffito lines into the large, oppressively dark solid plane of his head. Behind him, Eisenman has painted weighty books such as Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, Hannah Arendt’s Totalitarianism, and Roland Barthes’s Responsibility of Forms. Each one is painted with trompe l’oeil-style precision, and they all feel like little clues about the show. Of course the most prominent clue/book is Camus’s The Stranger, which leads into a spinning feedback loop in our search for meaning.

The overtones of Eisenman’s show are echoed in turn by Wynne Greenwood’s siren song, which seeps from her show own show in Vielmetter’s fourth gallery space out into Eisenman’s final room of paintings. “The security of having purpose. The security of having purpose. The security of having purpose” repeats like a mantra as footage of videotapes projects onto the floor.

Nicole Eisenman and Wynne Greenwood, ArtBasel Miami Beach 2007, performance. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

While many galleries in LA often feature concurrent solo shows by different artists, it is rare that the different exhibitions relate directly to one another. Yet Eisenman and Greenwood enhance each other, both exploring the tension between humor and sadness, combining references to light cartoons with grand gestures. They even collaborated in a 2007 performance at Art Basel, which Greenwood then cut into a video entitled Young Woman Warrior Prepared for Battle. Eisenman paints Greenwood into a cartoon interior painted backdrop. The two create various silly and strange vignettes; Eisenman paints Nike swoosh shoes onto Greenwood’s feet, who in turn pantomimes lacing them up. Eisenman extends the corner of a table onto Greenwood’s lap, upon which Greenwood draws a pizza and then mimes eating it. They giggle as Eisenman turns Greenwood into a cubist portrait, giving her extra eyes and noses. They turn her arms into a landscape horizon line. They attach joke shop bullet hole stickers to her face and gold leaf to her hair.

It’s fascinating to see Greenwood collaborate with another person, since she initially become known as part of a “collaboration” with her self/selves as the riot grrrl pop band Tracy + the Plastics. In live performances Greenwood would appear in the flesh as Tracy, interacting with pre-recorded video projections of herself dressed as the Plastics – Nikki and Cola. They all played different instruments, sang, chatted, and argued.

Wynne Greenwood, still from "Pregnant Medusa." Single-channel video projection in "Women's Spa," 2011. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Though Greenwood retired Tracy + the Plastics in 2006, her conversations with herself reappear in the installation currently on view. Greenwood’s voice overlaps with itself, emanating from multiple DVD projections. Next to the aforementioned video, another projection features two Claymation Medusa busts in conversation with one another.

“I really want to look at my own vagina.”

“You haven’t done that yet?”

“I haven’t done that yet. I want to do that. How will I do that? I can’t just bend over to look at it so I need something…”

Watching the phallic snakes write around on each scalp as the figures contemplate self-reflection, it’s tempting to psychoanalyze the work. The video begins to switch off between the heads, now discussing rules of domesticity, and a bedraggled version of Pebbles Flintstone, crying as she exclaims, “Fuck! What am I mad at?… I’m rotting…” Certainly, the image of innocent Pebbles’s frown lines exaggerated as though she is a middle-aged woman in the body of a toddler, is disturbing. But at the same time, it feels hopeful, in a way, to see the vapid baby re-imagined as a being capable of mature emotion. While the first video jumps from shots of Mickey Mouse memorabilia, to feminine images of roses, sunsets, and baby birds, a third video, partly projected against the wall and hand-printed white fabric strewn across the floor, shows a female figure, ostensibly in a spa setting, adjusting a white towel against her naked body, crouching and possibly weeping.

Wynne Greenwood, "Women's Spa," 2011. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Like Eisenman’s nods to other authors and painters, Greenwood’s quotations of pop cultural ephemera take on a brand new–and infinitely more complex–life in her work. Both exhibitions deploy appropriation and comedy as points of entry, to explore more complex ideas of alienation and anguish, but also love and revelation. Perhaps it is our ability to experience all range of these e that allows us to connect. Through that we reach out to the eternal through the intimately fleeting experiences sadness and pleasure, and this aspect of Greenwood’s show is suggested in its title, How We Pray. It weaves itself seamlessly into its spot next to Eisenman’s list of 77 titles.