When I asked Anne Wilson if I could interview her for Art21, she sent me a preview copy of her book, Anne Wilson: Wind/Rewind/Weave—a catalogue published collaboratively by White Walls and The Knoxville Museum of Art. It was a good place to start. In the second essay, curator Chris Molinski writes, “Anne Wilson: Wind/Rewind/Weave consists of three distinct projects: Wind Up: Walking the Warp (2008), Rewinds (2010), and Local Industry (2010). These projects represent the work of 2,100 community volunteers, seventy-nine weavers, and dozens of studio assistants working in glass, thread, video, sound and live performance.” While Wilson’s work is significant for its individual, sculptural, and material aesthetic, it is also reliant on the energy of others. not simply because those others are invested in her practice for its own sake, but because her practice speaks to larger questions embedded in textiles.

Quilting and weaving are inherited skills that have been part of the human experience for eons. The textile industry employs massive numbers of people and is now located primarily overseas. These aspects are simultaneously present in all three projects. In Sites of Production, another essay in the catalogue, Julia Bryan-Wilson asks, “Stop reading for one second and look down. What are you wearing?” Because everybody wears clothes, and those clothes come from somewhere. People make them. Wilson’s work touches on the migration of industry, locating the exhibition in Knoxville, Tennessee, within the southeastern U.S. most identified with histories of industrial textile production as well as hand weaving traditions. A history of settlement schools in the Appalachian mountains allowed women to raise extra income through hand weaving. According to Philis Alvic in her catalogue contribution, those women were in charge of how they spent that money. Here, too, we see how Wilson highlights issues of power and gender and history: the tradition of knowledge, the empowerment of skill-sharing and making. In Walking the Warp, she also addresses labor conditions, engaging the repetitive work of weaving: what it takes to walk a warp as a performance: how often the performers take breaks, what they do, how their bodies are on the one hand restricted by the demands of their task, and how those restrictions create opportunities for freedom at such times when breaks are had.

Everything Wilson does is precise and deliberate; she creates an aesthetic experience autonomous to the conceptual framework she is working within. For that reason, there is light and air in the space her practice occupies; it is evident in the catalogue, already rich with various interacting themes and interpretations as well as textual excerpts from the artist herself, photographs of the work, and visual excerpts from a gathered archive of weaving samples from all over the world. The book reinforced what has always been an intuitive impression of mine, namely that while Wilson establishes a formal connection with the viewer, her work is supported by a meaty conceptual framework both critical and optimistic. My knowledge of Wilson’s work was concentrated on her more recent projects, beginning in 2008 when I saw her show at Rhona Hoffman Gallery. I wanted to find out more about what led up to this point, and how she locates her practice within contemporary and material culture.

Caroline Picard: How do you think about scale?

Anne Wilson: In terms of scale, and the implication of larger worlds suggested my work, I’d like to first talk about how I came to work this way in the first place, with horizontal fields.

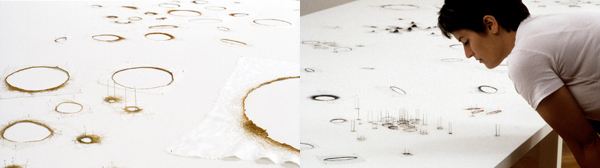

In the Fall of 2000, I had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. In addition to a range of other works utilizing found cloth and hair, I made a large sculpture called Feast that occupied its own exhibition space. Feast was a huge table, 22′ in length, and the stitched holes and tears from table linen — a vocabulary of parts stitched over 10 years — were placed back onto the horizontal table surface creating a kind of abstract topography. In developing Feast, I wanted to investigate aspects of perception, the optical imagination and relational ideas extending from the body and social space. I became interested in new ideas suggested by the horizontal format; ideas to do with mapping, navigation, architecture, and landscape. Also the power of a raking view—looking both down and across at a field of complex activity. This was the first piece that proposed this dual scale, suggesting both micro and macro worlds.

CP: Is that where Topologies came from?

AW: Topologies extended from Feast. Topologies was first made for the 2002 Whitney Biennial and re-made at 5 subsequent venues. It’s comprised of a large horizontal field of partly deconstructed and partly re-made lace fragments which integrate and disintegrate symbols of sexual and domestic decorum. Despite the materially embedded histories of lace, this new work resisted attempts to analyze or clarify any one overall formal or didactic sensibility. I set about working within a conceptual structure in creating Topologies that allowed three references to exist simultaneously: relationships between traditional systems of materiality (textile networks) and newer systems (Internet and the web); microscopic, specimen-like images of biology and the internal body; and macro views of urban sprawl — systems of organization of city structures, interdependent or parasitic processes of expansion.

At the same time, I began reading new texts about interconnectivity and relational concepts from recent architectural theory, new media studies, and philosophy. I was finding that a lot of other artists, architects, and designers were responding to the integration of related themes and ideas.

CP: What do you mean?

AW: I went to an exhibition curated by the Chicago architect Douglas Garafalo, and his opening curatorial statement directly related to the position my work was taking. Garafalo said: “While our society faces a growing fragmentation and specialization that seems at times to alienate us all, we have also started to view our world as a series of integrated, even entangled networks. One way we can begin to understand this contradictory state is as a matrix of field phenomena — repetitive patterns of texture, growth, turbulence, sound, light, etc., within a given system or space.”

The third work of mine that proposes relationships between micro and macro, dual scales, is Portable City, first shown in 2008 at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago. It’s comprised of 47 variable-sized vitrines that make another horizontal topography; positioned as both conceptual drawings and theoretical architectural proposals. However, in this project each vitrine is fixed as a unit, not remade each time as in Topologies, and the vitrines are mobile with the potential to create a changing population in relation to each other and a site.

Within all 3 projects, I think of the metaphor of landscapes too, in the broadest sense. Also references to those spaces that invite close observation and tremendous projection like large architectural models, expansive train sets, relief maps, and certain kinds of presentations or display tables of historical collections. In that regard, I placed benches around the Topologies platform to reference a kind of study table inviting close, extended examination.

CP: On the one hand, I do want to make a literal connection between your sculptures and human habitats but at the same time, your forms never quite transition all the way. They always remain abstractions. Could you talk a little bit about that?

AW: Yes, it is my intent that the work remains essentially abstract. I think of Portable City, for example, as an intense meditation on building and rebuilding, suggesting forms that never completely coalesce into overt representation — linear pathways at different elevations, stacks and parts under compression or suspension — suggesting a condition pre- or post-construction.

Each vitrine in the Portable City holds a structure made entirely by beginning with a spool of thread or wire filament — other than small nails and pins, there are no found objects. The essentially constructed nature of the Portable City also supports abstraction — working with ideas that extend from the elemental processes of textile construction, especially the repetitions of taut parallel lines as riffs on the process of warp making. Warping is the first step in the making of a weave structure; a warp is actually half of a weave — an essential and elemental part of a new construction.

CP: What happens, for you, when you blow up the scale? How does your experience of the piece change when it is performed in real time?

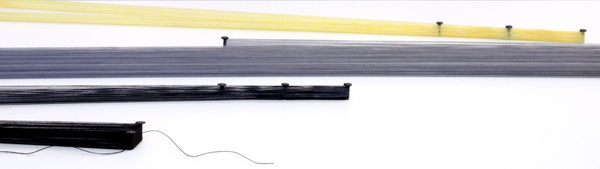

AW: The performing of a warping process was a direct extension of some of the perceptual principles in the Portable City, related to ways in which architects may work, imagining ideas on a small scale and modeling subsequent physical iterations on a larger, human scale. The first performance of Wind-Up: Walking the Warp was in the same exhibition as the Portable City, located in the front gallery of Rhona Hoffman.

Over 8 months prior to the January 2008 performance, a group of 10 of us worked on quite a complicated sequence of actions and group logistics of winding a warp on a metal floor frame. In the 6 days of the gallery performance, we collectively walked 33 miles to make a 40-yard long weaving warp using a yellow-green neon-colored thread.

Walking the Warp was re-staged last spring in a 2-part performance at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. For this performance, I partnered with the Houston-based professional dance ensemble called Hope Stone and all the fiber we used was donated from U.S. textile mills. And it was quite a different experience than the Chicago project. I needed to choreograph each and every line of color and direct the color shift in silence. The dancers’ memory of rotation and movement sequencing was phenomenal. One of most fascinating parts of the movement was what the dancers looked like when they stretched every hour during the two, 5-hour performances — combining gyrokensis, pilates, and yoga movements all in unison.

Performing exercise was a critical part of these performances — to expose the means of sustaining our bodies over long time periods of continuous repetitive movement. We were working from the inside of a making process and through our direct physical participation, thinking about time, labor, art, and cultural production. Writer Lydia Matthews uses a term called “participatory knowledge” — a term with a lineage back to Buddhism.

Anne Wilson, “Wind-Up: Walking the Warp Houston,” performance with Hope Stone Dance, CAM Houston, 2010. Photo: Simon Gentry.

CP: I think it’s interesting because I feel like you’re making a performance about work, too. Namely that the freedom between labor becomes meaningful, and even those literal movements made by the participants are contextualized by the repetitive movements required by the warp…

AW: The work is a performance about work! Actually my last 3 years of research towards the spring 2010 exhibition Anne Wilson: Wind/Rewind/Weave at the Knoxville Museum of Art investigates the crisis of production and skill-based textile labor. We were thoughtful of the complicated issues surrounding textile manufacture — the human rights of workers, living wages, and the freedom to voice grievances. Included in the exhibition was Rewinds, a new work created entirely in glass; video documentation of the 2008 Chicago performance of Wind-Up: Walking the Warp; and a large site-specific project, Local Industry, that took the form of an active weaving factory set up in a large museum space. Run over the course of several months, this factory involved the Knoxville community in the collaborative production of a unique bolt of cloth. Local Industry was both live performance and true production! Earlier this month a second exhibition opened at the KMA called Local Industry Cloth. Now part of the Museum’s permanent collection, this 76’ cloth length was collaboratively produced by myself and 78 experienced weavers and over 2000 bobbin winders in the museum factory.

CP: Another thing that comes to mind is the way you are participating in a historical lineage — knowledge of the warp and weft seems like something akin to bread-making, where it is made and has been made all over the world for centuries.

AW: It’s true! I really do think of my art as a kind of conjunction between visual art concepts and material culture, where the histories embedded in materials and the way things are made are critically important to the content of the work. I’m interested in the ways in which ancient handwork traditions intersect with that which is most contemporary – hand looms to digital jacquard weaving; transportable soft shelters from tents to new tensile constructions.

CP: This seems like the sort of question that should have come earlier, but can you talk a little bit about how you came to work in fiber? Who do you draw on for inspiration?

AW: There are so many individual artists who have informed my work and thinking. When I was a student I was deeply affected by the work of Eve Hesse, Robert Morris, Robert Rauschenberg, Ritzi and Peter Jacobi, and Magdalena Abakanowicz. As well, a history of work and ideas within the frames of feminism, queer theory, multi-culturalism, and the inclusion of non-Western aesthetics within a contemporary art discourse, globalism, Arte Povera, and the Art Fabric movement of the 1960s and 70s.

I am very interested in the current critical discourse around the word “craft” — I’ll call it “post-craft” — including the complementary relationship of hand and digital processing in contemporary art.

CP: Can you talk more about that? And where would you locate your work? Craft? Post-craft? Or simply contemporary art?

AW: I locate my work in contemporary art, acknowledging intersections with many different histories and lineages. Within highly technological societies, like ours, there is a renewed enthusiasm for crafting and tactility — in making physical things — a political response for some artists to the issues around manufacture of our consumer goods; for others, this renewed interest in hand-making is a response to the ways in which the digital, the computer screen, has so completely infiltrated many of our lives. The saturation of the digital demands a more direct connection with materiality and sensorial experience. Of course there are many other personal and specifically cultural motivations, but I do see contemporary art now embracing non-Western aesthetics, diverse forms of both analog and digital production, and a renewed critical engagement with material practices.

Anne Wilson and Local Industry weavers, “Local Industry Cloth,” Knoxville Museum of Art, 2011. Collection Knoxville Museum of Art.

The catalogue Anne Wilson: Wind/Rewind/Weave has just been published by the Knoxville Museum of Art in conjunction with WhiteWalls Inc. and is distributed by The University of Chicago Press. This 175-page publication includes essays by Glenn Adamson, Jenni Sorkin, Julia Bryan-Wilson, Philis Alvic, Laura Y. Liu, and curator Chris Molinski. The catalogue is available at the KMA bookstore and for purchase internationally through The University of Chicago Press later this year.

Pingback: Society of Contemporary Art Historians | Threading Infrastructure: An Interview with Anne Wilson

Pingback: Anne Wilson Art 21 blog « ART 577 CSULA