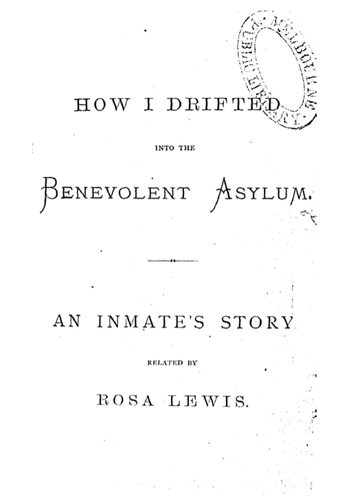

History isn’t was. History is. No matter how much we wipe our feet at the front door, we track history through the house. Leaving its muddy footprints all over the carpet.

This quote is from Phillip Adams, one of Australia’s most respected broadcasters and a left-wing atheist humanist who happens to write for a national and mostly right-wing newspaper. He’s also on the advisory board of WikiLeaks, so it’s quite telling that this quote makes an appearance in Australian artist Lily Hibberd’s latest work, one that unravels some of the gruesome history of institutionalization.

Lily Hibberd has always been interested in ideas of love and time (and let’s be honest, who hasn’t?), but her overall practice is difficult to describe, only as it has evolved so much in recent years. As a painter, her early works show an interest in pictorial illusion of cinema, such as the Blinded by the Light series, large canvases of recreated film stills that glow in the dark with phosphorescence. I still remember when the lights were switched off for the opening night at a gallery in Melbourne some years ago and a shocked woman spilled her drink all over me then spent the rest of the night apologizing. But the same woman also introduced me to someone who would become a fantastic lover, so both the evening and the paintings have always stayed with me and I’ve followed Lily’s practice ever since. The lover, alas, moved into the vestiges of time.

Lily Hibberd, "Blinded by the Light," oil and phosphorescent paint on canvas, 91 x 153 cm, 2002.

Then there are other series, like Paint Tin Fantasias, where characters confront their own delusions in famous movie scenes, each recreated in oil and pigment, shimmering and swirling inside old paint tins. And again, later works including I Want To Break Free, which saw her paint urban scenes that went to extreme ends with subjects such as death-by-dishwasher and other domestic disaster scenarios.

Lily Hibberd, "Paint Tin Fantasias," pigment, oil paint, tins, 2004

Since then, Hibberd has moved onto more challenging historical and performance-installation projects, such as the large-scale work from 2008, Bordertown, a monolithic black sound wall featuring audio narratives from two women who lived in a divided community on two sides of a remote state border.

Lily Hibberd, "Bordertown" (installation view), wood, paint, speakers, computer, Artspace, Sydney, 2008.

When thinking about how Hibberd reached this point from painting to examining Australia’s dark penal and mental institution history – a search that took her to London and Paris and back to some remote albeit scenic places in Australia – it seems that much of her oeuvre shows people being confronted with the unknown, or what they consider to be the unknown, when in reality, it is something they have deliberately forgotten.

Hibberd’s latest work, Benevolent Asylum, has taken more than three years of research and development and has seen her travel to the far corners of Australia and the other side of the world numerous times. With uncomfortable themes of deportation, containment, asylum, imprisonment, and the various inhumane practices of mental and prison institutions from the 16th century onwards, the legacy of these philosophies is still being felt today. Sometimes it is only in the memory of an abandoned institution, like those that Hibberd has documented in video and photography, but more often than not they are still felt in the treatment of detainees in institutions the world over.

The standardized model of solitary confinement – locking up prisoners or mental patients for years in complete isolation – first emerged in government policies in France and Britain before making its way to the colonies, which, in the 17th and 18th centuries, were still sizable portions of the planet. The practice of tiny dank cells and brutal seclusion essentially formed the foundations of modern Australia, at least the sort of foundations that most of the public would prefer to leave behind. A brief examination of Australian art and popular culture will show you that we either glorify or completely ignore the darkness and violence that seeded the new southern Antipodes. So for decades, the colonies swelled under policies of locking people up for the pettiest of reasons, then sending them to the most remote places in the world, at the edge of a desert on an enormous island and surrounded by vast oceans of landless time. And never mind the true custodians, that’s another story altogether.

Benevolent Asylum has taken its lead from seminal artists in the New York City of the 1960s and ’70s, who pushed the nexus of early installation and performance art. Hibberd mentions particular influences, such as theater and installation artist Robert Wilson, who created props as integrated artworks in their own right. Other key influences include the multi-discipline elements of Robert Morris’s installations, as well as the gesture work of choreographer Yvonne Rainer.

In reference to all these artists, Hibberd sees the ways in which contemporary practice has forgotten many of its origins in installation and performance art. Forms that originated in a more pure and tight engagement, but have since drifted apart into distinct fields, are something she laments and relates back to her own documentary fiction writing and the interactive set design for Benevolent Asylum with its Brechtian implications.

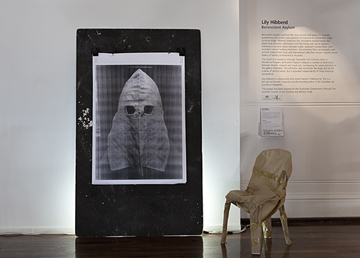

Lily Hibberd, "Benevolent Asylum" (installation view), board, photographic print, chair, paper, tape featuring Silence Hood from Old Melbourne Gaol Museum Collection, variable dimensions, Fremantle Arts Centre, WA, 2011

Much of the visual research material plays out through seven videos included in the show, featuring footage taken at sites of abandoned prisons and former prison hospitals in London, Paris, Sydney, Fremantle, Melbourne, and various remote islands and towns across Australia. Hibberd wrote and designed a research book to accompany her installation set pieces, as well as writing and directing a performance called Take Me In. The hour-long piece occurs within the physical structure of the exhibition at the Fremantle Arts Centre, where she was an artist-in-residence.

Two local actors, Siobhan Dow-Hall and Allan Girod, shift between playing out historical narrative and fictional characterization. Together, the actors provide the video works with historical context before slipping back into character roles to recite the personal trauma of their incarcerations. The pair heavily utilizes the sculptural objects in the exhibition, turning them into imaginary places: docks on parting shores; cramped and filthy ships for months of sea travel; and their final tragic destinations inside tiny cells of isolation. The audience is kept deliberately small in number and is seated with a wide spacing inside the gallery, potentially amplifying the experiences of the characters.

Hanging above the center of the space is a light work of an eclipse that slowly moves through its umbra stages, acting as a visual metaphor of the shift from darkness (the past) to light (the future). The first phase, Prediction, is a “premonition of exile and colonization.” The second phase is Totality, the confinement in one of the most distant and unforgiving places on the planet. The final phase, Recollection, represents at once “the hope of recuperation of collective memory” and the “public amnesia” of places that were once horrendous prisons and are now promoted as dream locales for tourists looking for sunshine and maybe a hit of schadenfreude.

Lily Hibberd, "Benevolent Asylum" (installation view), wood, rope, hooks, pulleys, televisions, DVD players, chairs, paper, tape, projection, posters, photographs, variable dimensions, Fremantle Arts Centre, WA, 2011.

The USA cannot hope to pretend that its history is so very different, with its respective treatment of “terrorist suspects” in prisons of torture, in the same way Australia has “illegal immigrants” in detention centers. These are the same kinds of actions that our two countries use to launch accusations of human rights violations against other countries. The example of admonishing China for detaining an artist like Ai Weiwei is essentially a non sequitur. Ultimately, Hibberd’s work demonstrates how long-term detainment and isolation without due legal process will never be a solution for justice; instead it has become a further and historically justified degradation of the human psyche.

The outcome of Hibberd’s histories and her historical fictions leave us with a certain ambiguity. As in all Hibberd’s work, she provides the tools and materials but leaves any kind of making or remaking up to the audience. Even her characters reach the end of their wretched stories with the parting words:

WARD: So tell me, is this a refuge or a prison?

BEA: I don’t know. Maybe the best we can hope for is a benevolent asylum.

I also managed to get a phone interview with Lily while she was in the middle of rehearsals. The performance opens this week, while the exhibition has been running since May 21. We spoke about some of the deeper ideas at work in the Benevolent Asylum…

Din Heagney: How do you think people in today’s context will react to some of the dark pathos of the material?

Lily Hibberd: There’s the contemporaneous argument in the content, the topical and political issue of asylum, of imprisonment, incarceration, and treatment of refugees, mental health patients, and criminals. Some people in the audience may find it negative while others may see it as entertainment. This is not in a traditional theatre or even a space that would usually host this kind of work, so I’m not at all sure how people will react. There are some historians coming so they are sure to want to talk about it and especially about the book accompanying the exhibition.

DH: The research for this project has been quite a while in the making, hasn’t it?

LH: My real interest started out in discovering a former asylum just near my home in North Melbourne. I’d also been thinking about Larundle (a mental asylum) and abandoned institutions for a while before that. So it’s been about three and half years of research. From the local research and archives, I made connections and links around the world, after meeting with various curators at museums, it all snowballed from there.

DH: Do you see this body of work having a direct link with the ongoing debate about mandatory detention of asylum seekers?

LH: Yes, very much so. The current system in Australia is founded on the same principles of confinement and punishment. If you look at the core of every one of our institutions, whether they be psychiatric or penal institutions, what they all share is solitary confinement as the apotheosis of punishment by the system. So if somebody is out of control or under ultimatum, then the person will go into solitary. Solitary confinement cells are the same everywhere. This was very revealing for me in pinpointing what is really going on: everyone is creeping around the edges of what’s debatable, and that is whether this is a right or wrong thing to do. I’m not debating that in this work, because I don’t know the answer. The question of incarceration per se is so deep rooted in human civilization, and since it was invented, we really don’t know what else to do. So that’s another question and not one I am in a position to address.

DH: There are themes of time and forgetting in many of your works, and perhaps even more so in this piece?

LH: What I’m interested in is unpacking how history operates within this paradigm. And how historical forgetting has been used to whitewash practices of solitary confinement inside our major institutions. It’s very hard for people to face the ideas of isolation as punishment in prisons or detention centers. People don’t really want to know about that. But it’s still prevalent in the world and it’s something that is actually inhumane. It’s used in some psych wards but how does that really help someone with a mental illness? They put caveats on it and say “oh well now they only stay in there for a few hours before they have to be seen by a doctor and they can be returned.” But the conditions inside those cells are a replica of the cells that come out of this tradition called the Solitary System, which came about in Pentonville in the north of London.

In Australia, many prisons were built on the same philosophy and these were called Model Prisons. The myth is that these were based on the Panopticon design of Jeremy Bentham from the late 1700s, you know, with the central observation tower and surveillance as a principle concept, but not one single of those prisons was ever built then. What was commissioned at the time was by a design by Bentham’s competitor, who won the contract with the British government to implement a new system, where you should incarcerate and isolate convicts for at least two years to begin with and often longer.

What they eventually found was that it caused such high rates of insanity, so at the time more than 25% of prisoners in Pentonville and Millbank, where the Tate Gallery is now, were going mad, yet the entire system was exported to Australia and ran right up until the late 20th century. Those cells were two by three meters and 23 hours of every day were spent inside the cell in total isolation with no verbal or visual contact with anyone or anything outside of the cell.

DH: Do you think things have changed since then, or are we just seeing the same thing played out in the military prisons in the United States or the detention policies of China and Australia?

LH: Yes, it is the same system of solitary confinement today. At Abu Ghraib, they used the same hours and employed the “silencers,” as they were called here, the hooded coverings worn over the head to prevent people from communicating verbally or visually with other people. The hood used in the work Take Me In is the one in the Pentridge Collection. What’s coming out in the US now, and I’ve been told there is a political campaign running about it, is that whistleblower, the bloke who released the government information about military actions to WikiLeaks, well that guy has apparently been in solitary for more than four months without any charges being brought out against him and they are using forms of torture. I think it’s endemic everywhere and the idea that Australians or Americans are any less horrific is just a myth.

This is where Foucault (Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison and The History of Madness) becomes interesting and the Parisian roots, that concealment of these systems, it’s like a public secret. Michael Taussig also talks about it in his book (Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative) as the thing that everybody knows but it’s so much at the core of a society that it’s hidden at the very center. It’s replicated for instance in the SuperMax prisons that are built now where the solitary cells are placed in the center core of the design because that’s where the prisoners are least likely to escape and also be totally concealed from public view. The practice is obvious in America and its military operations, everyone knows about it, the whole world knows about it now. But I think Foucault’s ideas of surveillance have been used incorrectly for whitewashing this insidious situation, but at the same time, the concept that you are being watched is a very powerful idea and it manipulates everyone. I’m also interested in Foucault’s notion of the inseparability of the mad person and the person who just doesn’t fit in, and their relegation to a space of exception like the prison or an island.

Benevolent Asylum

Lily Hibberd

Fremantle Arts Centre

21 May – 17 July 2011

(Performances 2-10 June)

Text, installation, photography, video & performance work Take Me In

Installation documentation by Christine Tomás

Lily Hibberd is represented by Galerie de Roussan in Paris.