Sanford Biggers, "Cheshire," 2008. In situ, aluminum, plexiglass, LEDs, timer, 67" x 33" x 10". Courtesy the artist and Michael Klein Arts, New York, NY.

Images from popular culture abound in Sanford Biggers’s work, and particularly from hip-hop, East Asian Buddhism, and the Antebellum and Afro-Futurist African-American. Two images that have become particularly emblematic for me among his works are the post-Pop Art-ish, cherry red lips of his signage-sculpture, Cheshire, in reference to the grinning cat made famous by Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. It is also the Buddhist Mandala, the patterns of which cover the floor-tiling of the artist’s Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II, upon which break-dancers pop, lock, and spin invoking the cosmic intuitions of the hip-hop dance form.

The images are telling of Biggers’s dual commitments. On the one hand, to a world of appearances, of masks that represent cultural and personal survival, the need to change one’s appearance in order to persist. If you recall, the Cheshire cat lost his body becoming only his grin in order to avoid decapitation by the Queens of Hearts in Carroll’s tale. On the other, there is an aspect of all of Biggers’s work that reaches towards the vertical, divine, and cosmic through the quotidian and culturally synthetic. A pair of nunchucks, one of the martial arts weapon revered by hip-hop and soul music in the 70s, is encased within a glass display (Nunchucks). In the installation, The Afronomical Ways, one enters a room with a mirrored floor. Upon the ceiling is a DayGlo Zodiac chart in which the signs of the Zodiac have been replaced by men and women making love in a variety of positions—a different position for each sign. In another piece, Hip Hop Ni Sasagu (In Fond Memory of Hip-Hop), Biggers has melted down hip-hop ‘bling’ (jewelry) into a set of bells that will eventually be played by an ensemble in Japan at a Zen Temple. Whereas one associates hip-hop jewelry with a very American form of materialism, one typified in many rap songs, melting them into bells transmutes them into forms both ephemeral and eternal, transitory yet specific. While, as Biggers notes in an interview, the bells will probably long outlast him, their tones linger and mix in the air only for a moment, struck among other bells—both ancient and newly cast—in the improvisatory performance of Hip Hop Ni Sasagu.

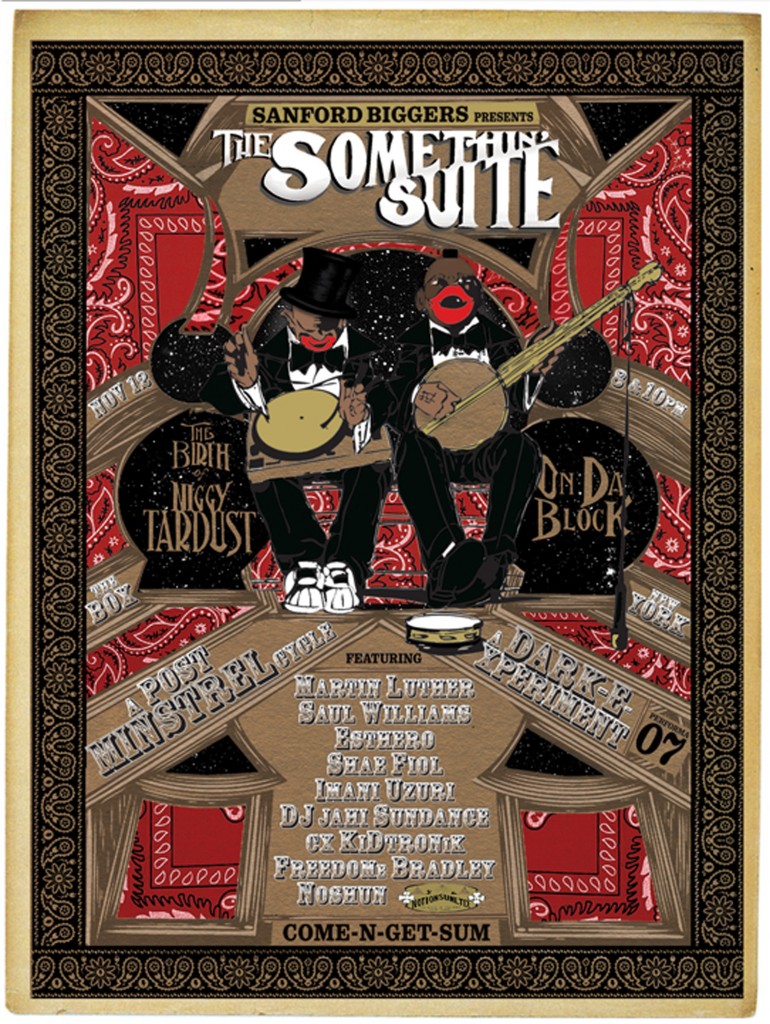

Sanford Biggers, "The Somethin' Suite," 2007. Multimedia performance commissioned by Performa 07, New York, NY. Courtesy the artist.

Biggers makes me think again and again of the culturally hybrid and plastic. While I don’t think his relationship to Buddhism/East Asian forms is at all insincere or put on, it also seems to me that almost anything could find a place in his inclusive cosmology—a cosmology that becomes commonplace in its ability to translate and transform disparate, if not at times antagonistic, cultural materials. The plastic qualities of Biggers’s work also reach backwards into time, exploring the future as a condition of the past, and vice versa. Some of this exploration involves an investigation of museum archives and curatorial regimes, such as in Nunchucks, but also in various works such as Olmec Afropick where Biggers has placed a wooden hair-pick depicting a clenched fist raised in the air, the image of Black Power, next to a sculpture of African origin depicting a similarly clenched and raised fist. In another work, Janus, one sees encased the head of Vanilla Ice opposite MC Hammer, repurposed from rap action figures of the two. Within the museum it is as though mythological time compresses and blends, conflating chronologies and heterogeneous cultural durations. Resemblances are struck, but they also clash and ricochet. As Biggers discusses below, works like his Jocko, which references the ubiquitous jockey lantern of many an American lawn, send one back to original cultural referents, referents that may have meant something radically different in their original contexts than they do today. So with time certain mytho-historical images crystallize, while others split apart, fragment, and obscure, following their divergent arrows of time.

As Biggers also discusses below, in recent works he increasingly explores different modes of live performance. One particularly stunning performance is The Somethin’ Suite. Performed at the Performa ’07 Biennial in New York City, the work is one of Biggers’s most explicit engagements with traditional and contemporary African-American forms—namely, the minstrel show as it is taken up by more recent African-American performance genres (jazz, funk, rap). As with many of Biggers’s works, though, there is a twist; the body disappears and all we see is the grin. Two white women sit on a swing singing the Negro National Anthem, the coloratura of their voices similar to those of African-American women. Could it be that their voices are wearing Black face, passing for the voices of their African-American counterparts? In another scene, Biggers’s collaborator, Imani Uzuri, sings a strained and grotesque version of the song made famous by Billie Holiday, Strange Fruit, while in the background one sees a video projection of Biggers’s friends climbing a tree dressed in the fashion of their various professions—one is clearly a lawyer, another a fencer. In other scenes we see a scene straight out of hip-hop videography—a rapper on stage with two full-bodied, female dancers who we see largely from the backside; and in another a scene straight out of Funkadelic or Africa Bambaataa, the performer Saul Williams as “Niggy Tardust” donning a coat comprised of peacock feathers (“The Ghettobird Tunic”) while singing, rapping, tarrying. In The Somethin’ Suite, Biggers’s cast evokes the many roles played by African-American and non African-American performers in reference to cultural histories that are still being written—revised, debated, transformed. The show seems to pay tribute, but it is also in keeping with the playfulness of all of Biggers’s works, which cite cultural survival through plasticity and ambivalence; the constant willingness to keep moving and changing throughout histories fraught with violence.

Sanford Biggers, "The Somethin' Suite," 2007. Multimedia performance commissioned by Performa 07, New York, NY. Courtesy the artist.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

I was first introduced to art through the works of a group of artists rarely if ever discussed in mainstream contemporary artist circles today. The paintings, drawings and prints of Charles White, Ernie Barnes, John Biggers, and Elizabeth Catlett (who’s amazing career survey, Stargazers, is presently on view at the Bronx museum) were just a few of the works I was exposed to as a youth. Though these artists were recognized in some circles, the two most popular being Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, they were quite marginalized with regards to the major art institutions of the US. However, amongst my parents and their friends, these were the artists that adorned the walls of their homes. Through figurative realism, these artists addressed the social and political state of African Americans through the 50s to the 80s and acted as an alternative education and media source for me as a child. This thrust of imbuing the aesthetic with historical and vernacular content is present in my work today.

As a teen, I was enrolled in AP art classes and attended Saturday art classes at the California African American Museum in South Central, LA. Around this time, I saw Wild Style, Charlie Ahearn’s seminal film about New York’s nascent hip-hop scene, and quickly began filling up black books, tagging and hitting up the train yards and vacant lots on the Westside. Albeit for only a few years, this along with the other B-Boy arts I was engaged in (break dancing and DJing), were pivotal in informing my future work with aspects of personal narrative, pop culture, and attitude.

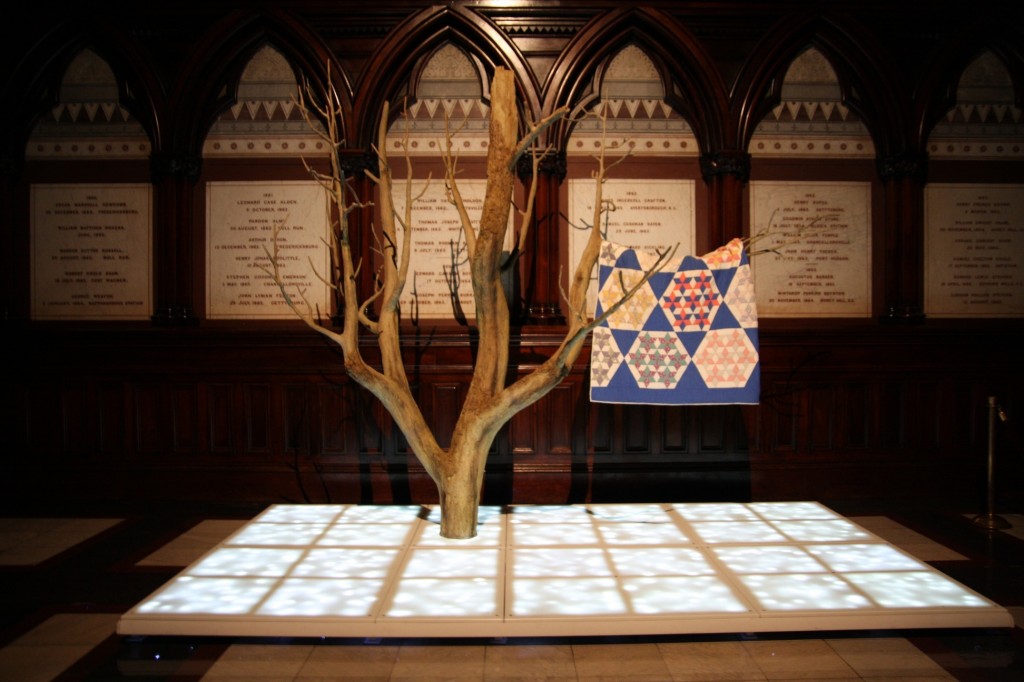

Sanford Biggers, "Bittersweet the Fruit," 2002. Tree (inside is a LCD monitor showing single channel color DVD with sound), headphones, glass bottles, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

2. Do you feel there’s a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

In the larger field of visual art, I’d like to believe that my work is unique and idiosyncratic enough to impact and challenge those who are following it, but the second part of that question is rather difficult. It’s hard to gauge what concrete effect, if any, a visual artist’s work has on civic responsibility and political action. I was told as a grad student that political art was futile and had no impact on larger society. Ironically, the summer before that, I was doing mural projects in Nickerson Gardens, where I was told that violence in the areas around the murals decreased significantly as the neighbors who helped to paint them took great pride in protecting and maintaining the area around them. (I knew that professor’s social experiences were, let’s say… limited).

But seriously, I consider the mural project I was involved with an example of civic responsibility and political action on at least a micro level. Take the work of Brett Cook Disney, for example. He is an aerosolist who has vigilantly pursued a body of work that consistently engages different demographics as they collaborate with him to create portraits of themselves and their community. While his projects end with beautifully rendered, spray painted paintings, installations, and murals, his involvement with respective communities includes sharing his yogic practice, political and pedagogical engagement, and self-empowerment through positive depiction.

I also consider materials and references to be laden with political meaning and part of the job of an artist is to poignantly compose and construct that meaning, not necessarily to provide answers, but to provoke better questions from the viewer. Artists like Alfredo Jaar, Emily Jacir, Swoon, Marina Abramovic, Santiago Sierra, Sigalit Landau, and Clifford Owens fall into this category by either directly or subtly engaging our political and social impetuses.

Sanford Biggers, "Jocko," 2006. Three chrome plated bronze casts.. 11 x 14 x 10". Courtesy the artist and Mary Goldman.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

Time is my recent fascination. By that I mean the effect that time has on history, how past truths are debunked over time through research and new understandings. For example, the New York Times recently reported that Memorial Day actually began on May 1, 1865, when Black workmen re-buried over 250 Union Army casualties and later, with other freedpeople, White missionaries and teachers, staged a 10,000 person parade and celebration.

I’ll provide a few examples from my own work. A few years ago I made a series of chrome plated lawn jockeys based on the story of Jocko Graves. Jocko was a stable boy who sought to fight alongside George Washington. Deemed too young, Jocko was ordered to maintain the stables and keep a lantern lit to guide troops home after battle. One evening, Washington and his troops returned finding Jocko frozen to death, still clenching the lantern. Touched, Washington erected a statue at Mount Vernon honoring Jocko. Later replicas evolved/devolved into the lawn jockeys we are more familiar with before being denounced as derogatory symbols after slavery. Ironically, some lawn jockeys were reportedly used as markers along the Underground Railroad. The three sculptures in the series Jocko, are frozen in a state of emergence and dissolution, symbolizing the conflicted history of Jocko and the lawn jockeys he inspired. Similarly, my recent repurposed quilt drawings entertain the contested history of whether or not quilts were used as “signposts” along the Underground Railroad.

Sanford Biggers, "Moon Medicine," 2011. Multimedia performance in conjunction with "Grain of Emptiness" at the Rubin Museum, New York, NY. Photo: Michael Palma.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

In 1998, I began an ongoing, video-documented performance where I placed an upright piano in the woods and over the course of two months regularly played jazz and gospel improvisations in the nude. This process was largely meditative and obviously quite liberating, but I had no idea what to do with the footage until shortly after, when James Byrd and Matthew Shepard were brutally killed in separate hate crimes. The resulting piece turned into Bittersweet the Fruit. It was comprised of the footage edited erratically to create an unsettling sound and videoscape that was shown on a tiny monitor embedded into the trunk of a tree surrounded by glass bottles. I learned a great deal about process in this work, and how sometimes the most ridiculous actions can find poignant applications.

“a small world…” was also done in 1998 with Jennifer Zackin. We poured through some 20-30 hours of Super-8 footage recorded by our fathers to find moments that captured the simultaneity and similarities of our childhoods. When we exhibited this at the Whitney, we showed it as a split-screen silent projection in a 70s-style family room with simulated wood paneling, an old sofa, and wall-to-wall shag carpeting. “a small world…” opened me up to collaboration, which remains a significant part of my work, as seen in my Performa 07 piece, The Somethin’ Suite.

Sanford Biggers, "a small world...," 2002. Collaboration with Jennifer Zackin. Silent single channel color DVD single channel projection. Installation: Shag carpet, 70s love seat, simulated wood paneling. Courtesy the artists.

The Somethin’ Suite is an ensemble piece riffing off of minstrel show tradition, where I directed a few musicians, poets, and DJs with whom I’ve worked on other projects over the years. The cast included Martin Luther, Saul Williams, Esthero, Imani Uzuri, Shae Fiol, CX Kidtronix, Jahi Sundance, and myself. This was my first multiplatform performance where I arranged and played a few piano compositions, included original video content soundtracked realtime by Imani Uzuri’s incredible a capella rendition of Strange Fruit, and costumed Saul Williams’ Niggy Tardust persona in my Ghetto Bird Tunic. The best part of this piece was improvising and showcasing all of the performers’ abilities within a conceptual stage format.

My most recent video project has been very exciting. It is a three-part suite entitled Shuffle, Shake, Shatter. The first installment, “Shuffle,” was shot in Stuttgart, Germany, and depicts a dreadlocked protagonist as he navigates German society by constantly putting on and taking off clown make-up. Via the clown mask metaphor, he is a stand-in for us all as we don various masks to matriculate and survive. This project has been particularly enjoyable because I met the main character, Ricardo, on a bus one night in Germany and consequently became good friends. In fact, we knew each other for about a year before I even approached him and his eight-year-old son to be in the project! Additionally, I traveled to Indonesia for three weeks, traveling between small towns and recording gamelan (traditional gong ensembles) music with a handheld recorder. Much like Bittersweet the Fruit, I wasn’t quite sure where this footage would go until after we filmed “Shuffle” and it made the perfect score. Following a similar process, Ricardo and I were just in Salvador Do Bahia, Brazil shooting the second video, “Shake.”

Sanford Biggers, still from "Shuffle (The Carnival Within)," 2009. Two-channel HD color video installation with sound component, 4:47 min. Courtesy the artist and Michael Klein Arts, New York, NY.

The common threads between all of these projects are the relationships that I’ve been fortunate to create with all of my collaborators. We share a similar vision and I wholeheartedly trust in all of their distinct abilities. Relying on their strengths allows me to construct the context in which to place them. From there, we just push “go.”

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I am an interdisciplinary artist, period. I’ve always worked in all directions and plan on continuing that way. With that being said, I would really like to explore a full-length feature project/collaboration with my focus primarily on the artistic direction or set design and musical components. I see this as the logical extension of The Somethin’ Suite, and the video suite Shuffle, Shake, Shatter, which is presently two-thirds complete. Simultaneously I am usually working on several drawings and flatworks. At the moment, I’m making collage-drawings with repurposed quilts and textiles juxtaposed with various mixed media. These more discreet works satisfy my need to create quicker works that keep my hands and eyes active while executing the larger, more labor-intensive projects.