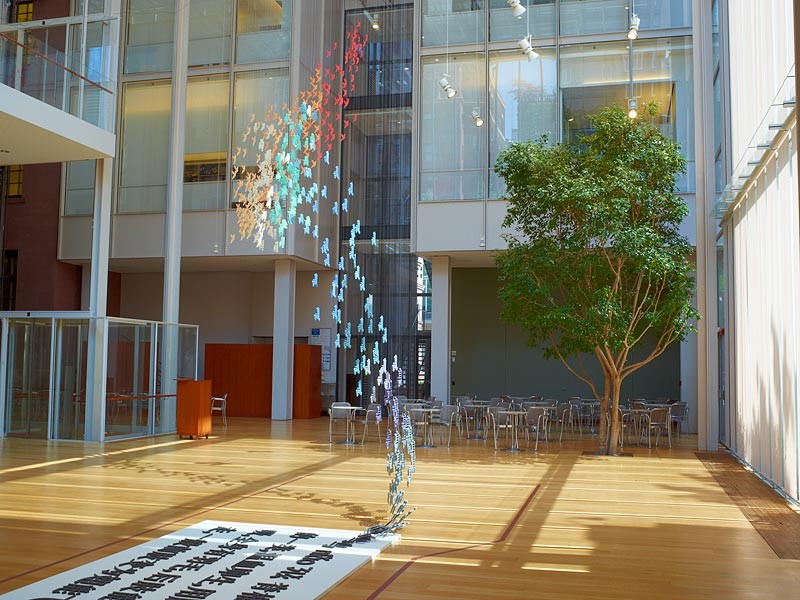

Xu Bing, "The Living Word," 2001 (partial installation view). Cut and painted acrylic. Courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum.

Perhaps the most seminal and certainly the most seismic moment in the history of Chinese contemporary art transpired at the National Gallery in Beijing in early February 1989. On the eve of the Chinese New Year and mere months before the tragic events in and around Tiananmen Square would begin to unfold, a group of curators organized an exhibition consisting of almost three hundred works by more than one hundred artists—an unprecedented and audacious aggregation of contemporary painting, sculpture, installations, and performances taking place in China’s most important and staid art institution. Officially titled China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition, it was also popularly known as the No U-Turn exhibition for the iconic red symbol typically found on street signage that organizers emblazoned on banners and carpets all around the National Gallery.

The National Art Gallery, Beijing, on the opening day of the "China Avant-Garde Exhibition," February 5, 1989. Courtesy University of Chicago Library.

Among the artists participating in the 1989 exhibition was Xu Bing, now widely regarded as one of the most important artists of his generation, and whose sculpture The Living Word—one of his most important works—is currently on view at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City. The Living Word, Xu’s third version of the piece but the first to be exhibited in New York, consists of 400 pieces of colored acrylic sheeting, each laser-cut into the form of the Chinese character for “bird,” and arranged in an undulating wave that rises from the ground to a height of about fifty feet. Viewing the work from bottom to top, the acrylic forms slowly metamorphose from the modern Chinese character for “bird” at ground level to more traditional calligraphic forms of the character, and finally take the shape of ancient pictograms based on natural bird forms at the top of the piece.

Xu Bing, "The Living Word," 2001 (partial installation view). Cut and painted acrylic. Courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum.

Xu Bing, who was born in Chongqing, China, in 1955 and grew up in Beijing, explains The Living Word as follows:

The dictionary definition of niao (bird) is written on the gallery floor in the simplified text created by Mao. The niao characters then break away from the confines of the literal definition and take flight through the installation space. As they rise into the air, the characters gradually change from the simplified text to standardized Chinese text and finally to the ancient Chinese pictograph for ‘bird.’ The characters are rainbow colored to create a magical, fairy-tale quality.

As the installation soars high above the ground, the dramatic, almost balletic transposition of the characters becomes an introspective critique of the legacy of Mao’s modern Chinese culture—represented in the intransigent materiality of the modern Chinese characters grounded firmly on the plinth on the floor—and a celebration of older enduring cultural forms. It is worth contextualizing the formal and conceptual movement back through Chinese history evident in The Living Word to the sentiments expressed by him and others who participated some two decades earlier in that momentous exhibition of 1989, sentiments that looked less to the distant past and more to the future.

Xu Bing, "The Living Word," 2001 (partial installation view). Cut and painted acrylic. Courtey The Morgan Library & Museum

The 1989 China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition involved a group of artists and art critics who, despite often intense political pressures, oppressive oversight and ongoing resistance to and attacks on cultural forms deemed part of a dangerous “bourgeois liberalism,” had come of age in the decade following the end of the Cultural Revolution and had haltingly emerged onto the art scene following the Communist Party’s decision in 1985 to permit modern artistic practices. The 1989 exhibition’s powerfully simple No U-Turn emblem signified the aspirations of the cadre of young artists, theorists, and curators that the precarious cultural reforms and freedoms gained must continue forward.

The exhibition was organized by Gao Minglu, Li Xianting, and others, and included besides Xu Bing such artists as Zhang Peilli, The Gao Brothers, Wang Guangyi, Gu Wenda, and Fang Lijun (to name but a few). Not surprisingly, preparations for the exhibition were closely monitored and censored by officials from the Ministry of Culture and the National Gallery. At the opening ceremony on the morning of February 5, Gao Minglu announced that “the first grand modern art exhibition of China organized by Chinese artists themselves is now open.” Despite the strict oversights and controls—and in a bold defiance of it—a frenetic scene unfolded as visitors swarmed into the galleries and besides confronting daring paintings, sculpture and installations, encountered provocative and spontaneous works of performance art, an art form that had never before been exhibited in China. By most accounts, the energized atmosphere was exhilarating, the frenetic scene dizzying and resembling something more akin to a street carnival than a staid official exhibition typical of the National Gallery.

Xiao Lu, "Dialogue," February 1989. Performance and mixed media installation. Courtesy China Heritage Daily.

Artists whose performance works had been forbidden from the show by officials prior to the opening performed their work anyway. Zhang Nian sat cross-legged on a straw mat on the floor surrounded by eggs, with a placard around his neck that read, “No theoretical debate during my floating egg performance, lest it troubles the next generation.” Performance artist Wu Shanzhuan sold prawns from on the first floor of the exhibition, attracting a large crowd of buyers for about thirty minutes until two plain-clothed police officers arrived, tore up his sign and escorted him away. Fined for illicit trading, Wu later reappeared at his stall, posting a sign that read, “closed temporarily for stocktaking.”

It was the artist Xiao Lu’s performance, however, that unleashed chaos, had uniformed police swarming into the exhibition space, and led to the closing of the China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition. Xiao’s installation/performance, Dialogue, consisted of two phone booths, each containing a dressed mannequin holding a telephone receiver. Between the two booths was a red phone with its receiver off the hook atop a pedestal, and placed before a large mirror that had a red cross painted on it. The assemblage was arranged atop concrete slabs laid on the floor meant to recreate a Beijing street. A few hours after the exhibition opening—in a move unanticipated by even the event organizers—Xiao positioned herself in front of her installation, pulled out a handgun and fired two live rounds at the central mirror, the second at the urging of her partner and collaborator Tang Song, who shouted from the crowd that had gathered to witness her action. Chaos ensued and Xiao and Tang were taken into custody by police. With Dialogue as a hyperbolic culmination to the events of the morning, officials shut down the China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition in its entirety within hours of its opening.

Among the non-performance works on view that day in February was Xu Bing’s A Book from the Sky. A Book from the Sky consisted of massive sheets of paper—long scrolls hanging from the gallery ceiling, affixed to the walls and piled on the floor—covered in Chinese characters. The hand-printed woodblock characters are in fact meaningless, characters invented by Xu using an ancient technique. Designed to look like Chinese text, Xu’s characters are in fact unintelligible and utterly empty, a wry and (subtle enough) commentary on the vacuity of Communist propaganda and the destruction of Chinese cultural heritage.

Xu Bing, “Book From the Sky,” 1987 (1992 installation view). Mixed media. Courtesy North Dakota Museum of Art.

The 1989 exhibition marked one of the first major artistic awakenings from a kind of cultural and historical amnesia brought on by Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a period whose penumbra cast a long shadow. In A Book From the Sky, Xu Bing evoked the past so as to critically examine his present and look to the future, and revealed an engagement with language, history, and cultural critique that continues to inform his work, including the Morgan Library’s The Living Word. But unlike the frenetic scene unfolding that February morning in 1989, the soaring majesty of Xu’s The Living Word—housed within the Morgan Library’s serene, light-filled atrium designed by Renzo Piano—expresses a catharsis only afforded by the passage of time. The sentiment embodied by the No U-Turn symbols of 1989 found perfect expression in the audaciously contemporary and provocative works that comprised the China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition. Born out of but not made in those turbulent times, Xu Bing’s The Living Word does not turn from the past but rather engages deeply with it, seemingly transforming the seismic convulsions of 1989 into a soaring, graceful form in which the advances made—often fleeting and spasmodic but significant nonetheless—and the cultural memory regained since the end of the Cultural Revolution seems reified into beautiful cultural product.

Xu Bing: The Living Word is on view at the Morgan Library in New York City through October 2, 2011.

Pingback: Xu Bing's Phoenix at MASS MoCA – Art & Lemons