Thea Liberty Nichols: While trying to determine how to define what it is that you do, I hit upon the idea of just describing all of your activities in one long run-on list, which might look something like this: publisher–distributor–writer–editor–curator–blogger–teacher. (Hopefully I haven’t made any glaring omissions?) I like the idea of employing awkward hyphenations in this instance because it not only emphasizes the reach of what you do— it also creates a sort of horizontal organization of things, were all of these different forms of expression and modes of production are recognized as equals, rubbing hyphenated elbows. Can you tell us a little more about the sum of these parts, or some of these parts?

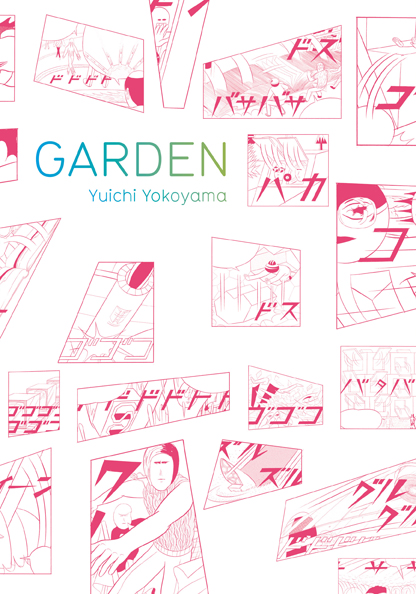

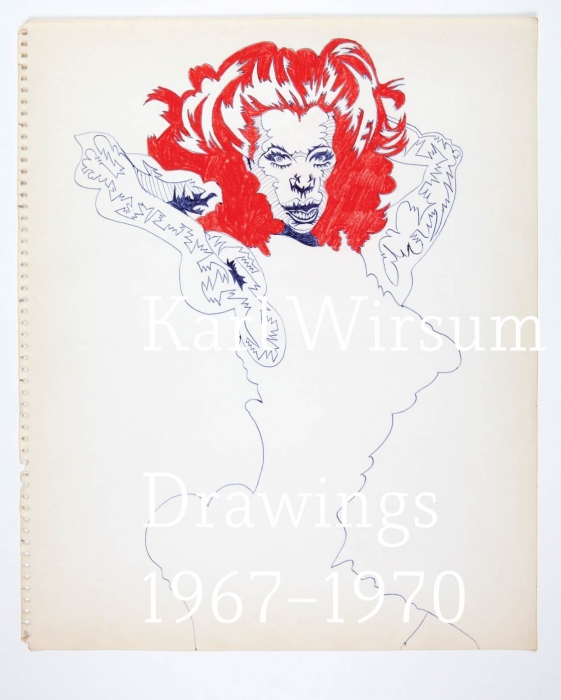

Dan Nadel: You summed it up pretty well! I see all these activities as interlocking. Basically I look for as many outlets for my sensibility, and those of my artists, as possible. The parts you reeled off are linked by my desire to present both the work of artists I’m interested in and the lineage they’re a part of. So, it’s important to me to not just publish, say, Gary Panter, but also to curate a retrospective of his work, and then look at his art history and publish or curate around that, too. So from Panter I got to the Hairy Who and Karl Wirsum, for example. And likewise, when publishing a younger artist, like C.F. or Yuichi Yokoyama, I’m interested in their total sensibility: in comics, in drawing, in music. The artists that I’m most involved with by necessity require the above linkages — I have to be all those things just to keep up with them. But I’m a bit evangelical, so while they prod me, I like to think I’m prodding them out into the public — and trying to create a space, both contemporary and historical, in which they can exist.

TLN: The works that you’ve produced over the years feature a wide-ranging slew of multi-generational and cross-disciplinary makers. In your collaborations with others on these projects, do you see yourself as a maker too, or more of an indefatigable fan and promoter?

DN: I definitely see myself as a maker, or a maker by way of facilitating. What keeps things interesting is the making — working with an artist or group of artists to determine the best way for their work to be experienced in the world. And as a writer/curator, I like to think I’m making ideas, or spaces for ideas — making the context in which this work lives. In other words, I’m not interested, for myself, in just dropping raw material into the world. I want to help form and inform it, and, to some degree, inform the response to it.

TLN: You’ve developed a lot of long-standing relationships with the cast of characters affiliated with PictureBox Inc., and I admire how you’re able to both track the emergence and blossoming of some while simultaneously unearthing or re-popularizing others, as only the best cultural anthropologists do. How do you see your creation of hard-copy print publications contributing to the existent mix of visual and cultural phenomena floating around us, bearing in mind the symmetry of publishing on comics, drawing and illustration alongside the dissonance of publishing on music, animation and web-based art?

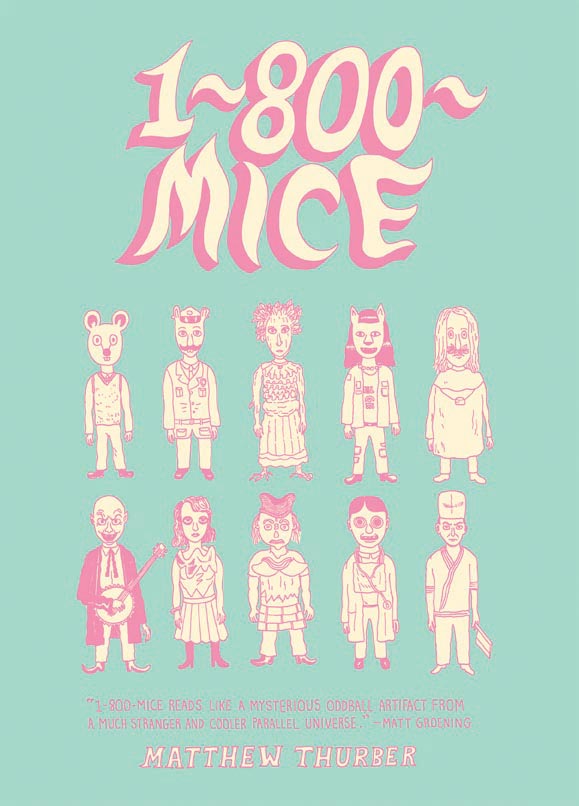

DN: I’ve always wanted to, in a sense, rewrite the history of post-WWII visual culture. And if anything, that’s what all my various activities are about. I also like to think that the artists and designers that form the core of PictureBox (Gary Panter, Ben Jones, Frank Santoro, C.F., Brian Chippendale, Norman Hathaway, Matthew Thurber, et al) are sui generis sensibilities whose contributions to culture are deep and long lasting. And what my various activities bring to the fore, I think, is an intelligent “other take” on visual culture. What if we overthrew traditional narratives of pop and post-conceptual art and installed Peter Saul, Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum, H.C. Westermann, and Gary Panter in the pantheon? What would that bring us to? Is it possible that the artists saying the most about being human have often been the most overlooked? I’ve explored that in various articles, exhibitions and books. And similarly, as I suggested in my books Art Out of Time and Art in Time, what if our standard quality-lit narrative of comic art history was widened, and talents once deemed eccentric were accorded status commensurate with the full merit of their work, like Fletcher Hanks, for example. I go after the lost work (like 1970s airbrush art in Overspray, for example) because in it I often find work that is pungent and often too overwhelming to have been properly recorded in the first place. So called imagism or certain parts of illustration. Avant-comics, etc. Therein I also find the richest lessons about how history gets made (often by the embarrassed). So… in a megalomaniacal way I guess I hope that by digging up the past and helping to produce the future, I can create some parallel space for ideas — and that that parallel will converge, or crash, into the other spaces, with interesting results.

Above all, though, I love the relationships I’ve formed, and the connections made between generations. It’s rewarding for me to learn lessons across generations, and also rewarding for the artists I work with to meet one another— to meet their spiritual heirs or mentors, and to see what comes of that. It’s endlessly fascinating and keeps me hopping.

Dan Nadel was born in Washington, D.C. in 1976. He is the owner of PictureBox, Inc., a Grammy Award-winning publishing company. Dan has authored books including Art Out of Time: Unknown Comic Visionaries, 1900–1969, Gary Panter, and Art in Time: Unknown Comic Book Adventures, 1940-1980; is the co-editor of The Comics Journal; and has published essays and criticism in The Washington Post, Frieze, and Bookforum. As a curator, he has mounted exhibitions including Karl Wirsum: Drawings 1967-1970 in New York, the first major Jack Kirby retrospective, The House that Jack Built in Lucerne, Switzerland, and Macronauts for the Athens 2007 Biennale in Greece. Dan lives in Brooklyn.