Artist, scholar, organizer, and professor, Gregory Sholette embodies multiple ways that artists can interrogate history, politics, and public discourse. Through his initial work with the group REPOhistory (1989-2000) (as in, “repossessing history”), he, along with other art groups and individuals of the 80s and early 90s, effectively drew attention to the artist as a social and political actor. Sholette’s collaborations with REPOhistory also presented art works as vehicles for addressing submerged socio-political histories, such as in the group’s Lower Manhattan Sign Project (1992-1993), in which they posted signs around Manhattan offering information about “the unknown or forgotten history of Manhattan below Chambers Street.” Sholette has also been an active participant in PAD/D (Political Art Documentation and Distribution [1980-1986]), an organization devoted to the publication and distribution of documents regarding the intersection of aesthetic politics and activism. Most recently Sholette has founded an archive for futures that “never happened” (The Imaginary Archive, 2010-present), and has been involved with The Institute for Wishful Thinking, an organization that attempts to harness the “untapped” potential of artists by soliciting proposals for projects which might effect governmental and social change.

Despite Sholette’s robust participation with other artists and activists and his tendency to only exhibit his own work in group shows, the works and projects he has produced independently of collaboration feedback vitally into a more collective practice (something he discusses at length below and in a previous “Inside the Artist’s Studio” feature). Meeting Sholette in person, I was struck by his interest in subjects ranging from the popular to the occult and counter-cultural. Sholette’s range of interests are brought to a focus in the book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, in which he considers artworks that have fallen through the cracks of official art-historical discourse. Such works offer sites of (potential) resistance and autonomy inasmuch as they are not perceived as “art” proper and so remain liminal to the expropriative tendencies of cultural capital. Works by the “outside” artist, the craft artist, the hobbyist, the amateur, and the self-critical “drop-out” appear throughout Sholette’s book, offering examples, if not models, of what art can do guided by different values and habits.

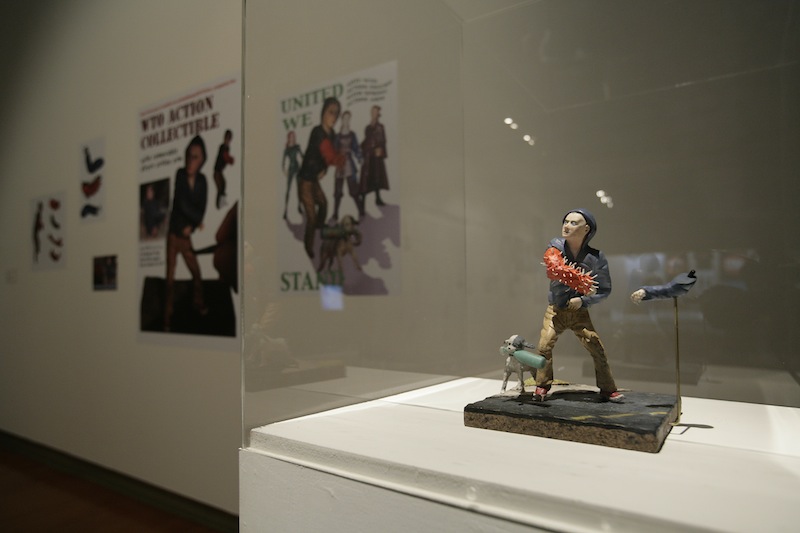

After the work of the film-essayist Chris Marker or the literary theorist Walter Benjamin (two professed heroes of the artist), Sholette turns his attention to the abandoned and unattended, cultural products so prosaic that they would seem neither worthy of our critical attention, nor our powers of reappropriation. The stuff ripe for re-use in Sholette’s work one would hardly call “redemptive,” and yet something is redeemed through the artist’s taking them up—a potential to make legible things just below the attention, what becomes “dark matter” because the culture at large just doesn’t know where to put it. Through the use of action figures in particular, a preferred format of hobbyists, he addresses problems ranging from post-Fordist labor practices (i am NOT my office, 2002-2004) to representations of Italian Fascism (Deconstructing Mussolini, 2007) and the exploitation of child workers (Little Workers Collectibles).

Sholette’s dirty messianic approach also comes across in his appropriation of dioramas, window and museum displays, and souvenirs. Playing upon our familiarity with these 19th century formats, Sholette moves fluidly between sentimentality and criticality, ironic abandon and the recognition that, as Walter Benjamin famously wrote (and Sholette quotes through a particular work of his citing the relationship between John D. Rockefeller’s founding of the New York MoMA and management of his public image after a mining disaster): “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Moving within the flicker of “civilization” and “barbarism,” Sholette tells history slant, through the eyes of the losers, the unrecognized (and unrecognizeable), citing the places where anomalies and antagonisms crucial to history’s retelling “flash-up.”

Oriented by the Cold War era (as he recognizes below), Sholette’s analysis of barbarism and civilization deconstructs American exceptionalism in the post-war period, particularly the ways that American art and the management of its geopolitical interests intersect. In his video Return of the Atomic Ghosts (2005), for example, Sholette spoofs extraterrestrial cover-up documentaries in order to reveal another cover-up of the previous half-century: the US government’s involvement in countless foreign coups, assassinations, and occupations.

In his bas relief, Men Making History/Making War, Sholette draws attention to the US government’s use of Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists to wage culture war against Soviet communism. In yet another work, Preparing for War (1983), exhibited at the Brooklyn Naval Terminal just before the US invasion of Grenada, he questions links between avant-garde Modernist art and the causes and repercussions of World War I, reproducing works by Duchamp, Picasso, Brancusi, and others from the period preceding the “great war.” Preparing for War reflects on the connections between war, nation building, and avant-gardism (a military term before it was used to describe certain art attitudes and practices). In another work, Express Yourself (1993), Sholette bronzes his American Express card, placing it among other bronze reproductions of well-known Expressionist art works. The message is clear: art is no longer the privileged site of self-expression (if it ever was) during a cultural moment in which buying power and creative potential (expression) are equated.

Buffering the seriousness of his political and social commitments, and his unflinching belief that art can intervene effectively in public discourse (if only through its counter-cultural potential), is a sense of the weird and wondrous, a commons of the odd. One gets this sense from a recent photo-installation work, Mole Light: God is truth and light his shadow (2010), wherein one views a series of cartoon eyes accompanied by thought balloon with quotations from Plato, Marx, Courbet, Glenn Beck, Snow White’s Grumpy, and others. In another work, appropriating the format of 50s television and radio commercials, Sholette provides a “recipe” for real estate futures (Cooking Up Real Estate Futures for Lower Manhattan, 2006). Heating up a track of land in Iraq through continuous missile fire, one need only cut out the piece of land and transplant it to Manhattan. Few artists I know strike so boldly and lovingly at the heart of the American project, creating sites where the American obsession with novelty and consumerism can collide with its geopolitical realities.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

Post-war America filled art schools with optimistic young artists like me: born in the middle of last Century from white, working class (but also home-owning) parents and taking seriously John F. Kennedy’s claim that the artists was “the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society” [from a speech by President John F. Kennedy given at Amherst College on October 26, 1963]. I imagined a future in which labor and pleasure converged. Then came the political and economic trauma of the late 1970s and early 1980 –the years I really began to come of age while moving to New York City from Philadelphia– which was not so much an end to that spirit of hopefulness, as much as it was a re-grounding of expectations within an oppositional space out on the far periphery of the art world.

2. Do you feel there a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

Work is a necessity. It defines us. I do not mean employment defines us, or your job defines us, or even “productive” work defines us (whatever that may be today). Rather simply the activity of being in the world requires us to exert a material force within it and sometimes against it (just as it in turn pushes against us). This definition of work of course includes both physical as well as mental capacity, and it could also mean refusing to be productive like the character Bartleby the Scrivener in Melville’s classic tale. Why? Because refusing to be productive is also a kind of activity that requires working at not working if you like. The young Marx put it most succinctly when he wrote that a human being only really works in the fullest sense of that word when free from the bridal of necessity. Being chained to the needs of the market economy is therefore the opposite of freedom.

This is where culture comes in. In the minds of most people the artist is the epitome of non-productive work. More than that, the artist also represents a kind of non-socialized work. She stands apart from the communal coil, traveling her own road, and that means the artist exists at the exact point of friction where the autonomous individual and the collective social need collide. At least this is the common character of the “artist”: a slightly or seriously anti-social human being. Most likely this sentiment leads to the always-present anxiety so many people (including those in the art world) express towards art that is produced collaboratively or collectively. My artistic labor consciously engages such acts of collaboration and collectivity. They become central to my production as an artist, and in fairness as a writer and teacher. I think some of these concerns are thrashed out in my new book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011). But does that mean any of this work is politically responsible or socially necessary?

While that is a fair question, Thom, I think it tends to collapse the contradictions mentioned above, contradictions between work and non-work, individual and social that are inherent to cultural production. Maybe a different question to ask is what necessary role does the non-social, and the concretely material play within the emerging arena of community art and social practice art? To put it differently: how does one learn to embrace not only an agency that is socially generated, often the easy part of a project, but also the active or inert resistance of a specific urban space or history or historical archive? This material resistance sometimes can be constructive, giving us something to push against. At other times it can stand in stolid opposition to our intentions, no matter how good they appear to be. It is a question that I think needs to be addressed right now especially as these civically-inspired artistic practices gain purchase within the worlds of contemporary art and academia. (Neither are these contradictions absent from my own “work.”)

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

- Moby Dick

- Wikileaks

- The poetry of Bertolt Brecht

- Chris Marker’s films Sans soleil and La jetée

- The dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History

- Martha Rosler’s videos, essays, and pedagogical texts

- Andrew Heminway’s treatise Artists on the Left

- Coleoptera (which make up 25% of all known life forms)

- J.P. Gorin’s docu-fictional cinema such as Routine Pleasures

- Weird new groups like themm.us

- Carol Duncan’s scholarship on museum semiotics

- Hans Haacke’s installations, public works, and critical research methodologies

- The Communist Manifesto

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

Certainly I am most proud of the work I did with REPOhistory in the 1990s, but especially the project CIRCULATION, whose concept I conceived of in 1995 and which the group realized in 2000. I am also very pleased with Mole Light: God is truth and light his shadow (2010), a site-specific installation I made for the unique exhibition space Plato’s Cave in Brooklyn.

Perhaps my all time favorite art “work” from the years past is Insurrection (1984) – a long, horizontal wall piece made with wax, latex, wood, plastic, paper, and a silkscreened text that measured 36″ x 106″ x 8″ inches. Insurrection was based on the writings of Ephram Squire who in 1849 was the Charge d’affaires for Central America under President Polk. The text describes Squire’s view that the non-white peoples and strange zoology of the region (now known as Nicaragua). He goes on to state that this odd flora and fauna will inevitably be superseded by the northern, animal and plant life (and its people will be supplanted by the “white race”). “Deus Vult – it is the will of god” he proclaims in the 19th Century language of Manifest Destiny. But in my piece, his words are gradually engulfed by a mat of foliage and flowers recreated using techniques I learned from a friend – Michael Anderson — an artist and exhibition technician who once worked on the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History. The piece was made with assistance from Anderson and was exhibited as part of the Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central American in 1984

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? In what directions do you imagine taking your work?

Right now, I am working on several new installations that combine conceptual and sculptural elements that grow out of and feed into my research on “Dark Matter.” All will be realized in collaboration with people I both like and admire:

Imaginary Archive is a collection of both real and fictional documents describing a future whose past did not exist (or a past whose present does not exist). The work takes the form of booklets, newspapers, small constructions, posters, some of which I created and others produced by a group of invited artists. Its first version was installed last June at Enjoy Public Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand (2010), and Imaginary Archive will continue as a second chapter this November at Gallery 126 in Galway, Ireland for the Tulca Arts Festival (2011).

The other project I am working on is Islands. It will open in February 2012 and is being made for the massive panorama of New York City at the Queens Museum of Art. Once again, this project will involve a group of collaborators, however this time I am interpreting their ideas, not asking them to make things. About ten people known for their critical writings about social practice art are being asked to imagine an island that appears unexpectedly off the shoals of New York City right after the ten-year anniversary of the 911 attacks. What kid of solitary land mass does someone concerned with social and political art envision? Will it be a communal space or more diffident, even private? I will be fabricating these visionary, scale-model islands and then have my collaborators pose with them before adding the islands (temporarily) to the QMA panorama.

Finally, I will also contribute to Temporary Services project for Creative Time’s Living As Form at the Essex Street Market in Manhattan in the Fall.