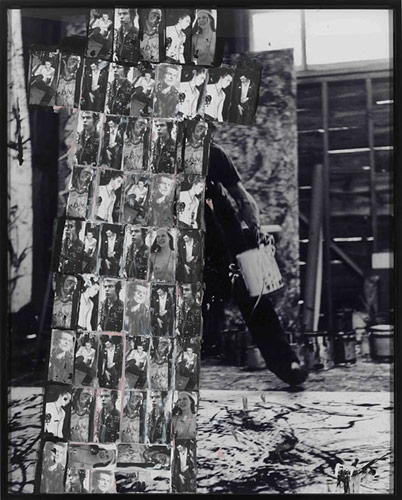

Richard Prince, "Untitled (Covering Pollock)," 2010. Collage and acrylic on c-print. 40 x 52 1/2 inches. Courtesy Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, and Guild Hall Museum.

“I am nature.” –Jackson Pollock

“We are all a combination of constructions and inventions, a mixture of truth and lies.” —Richard Prince

Richard Prince’s new body of work at Guild Hall in East Hampton, New York, continues the artist’s career-long preoccupation with using the images of mass media to explore issues of originality and uniqueness in art. The exhibition, titled Richard Prince: Covering Pollock, brings together a series of works in which Prince has layered images of punk rock musicians, swimsuit models, and vintage pornographic centerfolds atop photographs of the great Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock. The images of Pollock that Prince has selected (and selectively covered over) are largely culled from a book of photographs by Hans Namuth. The photographs reveal Pollock in the act of painting—his wife and fellow artist Lee Krasner perched on a stool observing him work, clusters of paint cans and brushes on the floor of his workspace—as well as views of Pollock’s bucolic Springs studio and of the overturned car from the crash that took Pollock’s life in the summer of 1956.

Onto these photographs Prince has collaged much smaller images of rock musicians and beautiful women, and occasionally even images of Pollock and Krasner themselves. Prince has collaged these smaller images into across the surfaces of the Pollock photographs in grid-like fashion, often repeating a select few images across the picture plane. In a number of these works the one prominent feature of Pollock left uncovered by Prince’s layering is the painter’s hand—that ultimate symbol of artistic creation—seen clutching either a brush or a cigarette.

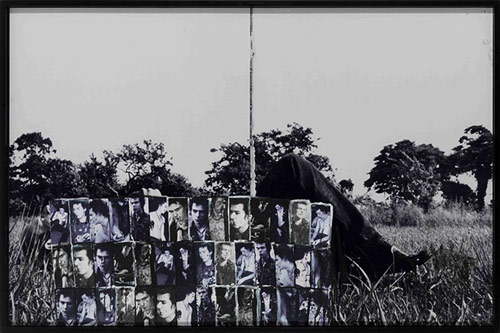

Richard Prince, "Untitled (Covering Pollock)," 2009. Collage and acrylic on c-print. 41 3/4 x 64 inches. Courtesy Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, and Guild Hall Museum.

In more than one instance, images of Sid Vicious—the charismatic bassist for the legendary punk rock group Sex Pistols—repeat with an almost casual purposeless across the surface of Prince’s compositions. These shots of Vicious, culled by Prince from mass media sources, show the musician in various moments of punk rock ecstasy, as well as in states of visible deterioration—in one he is seen in the ecstatic thralls of an on-stage performance, while in another he appears catatonic, lying on the ground in a presumably drug-induced stupor with microphone held limply in one hand. These images of Vicious resonate with the photographs of Pollock buried beneath them, wherein Pollock is (partially) seen either standing over a canvas that has been spread out on the studio floor, hand extended with loaded brush—a performative gestural flourish is frozen in time—or else he is seen sitting or even lying down with cigarette in hand, his body seemingly relaxed in a post-creation, almost post-coital state of exhaustion. Beyond these formal and conceptual similarities, it is also not to be lost on the viewer that Pollock and Vicious have both become almost mythical figures as creative archetypes, and who both lived mercurial, at times tormented lives that were cut tragically short.

The connection between Richard Prince and Pollock is also stronger than it might first appear, as both have ties to the East Hampton area: Prince is a part-time resident of the East End of Long Island, while Pollock lived, worked, and died just a few miles down the road from Guild Hall. But there is another connection that necessarily links the Appropriation artist to the iconic Abstract Expressionist painter across the arc of art history: Pollock was in many ways the poster child for modernism’s hallowed ideals of individual creative genius and authentic artistic expression, while Prince is in many ways the poster child for a postmodern moment that complicated and renounced those ideals.

Prince is often affiliated with the so-called Pictures Generation of the late 1970s and early 1980s, a loose group of artists that included Cindy Sherman, Jack Goldstein, and Sherrie Levine, who were known for appropriating images from mass culture, probing the role of visual culture in the conditioning of the American psyche, and for blurring the line in their art between what is authentic and what is formulaic artifice. While working for Time-Life at the outset of his career, Prince began making art in which he used or re-photographed advertising imagery. Perhaps the most notorious instance of this re-photography was Prince’s appropriation of Philip Morris’s iconic advertising figure, the Marlboro Man.

Richard Prince, "Untitled (Cowboy)," 1989. Ektacolor photograph. 50 x 70 inches. Courtesy Richard Prince.

Pollock can be viewed as something of a climax to Modernism’s notions of artistic genius and values of originality and authenticity couched in his unique artistic style, indexical painterly marks. In the American post-war age of mass production and reproduction, the hard drinking, asocial, and irascible Pollock and his artistic output marks high culture’s fetishizing of the unique and the original over the multiple. At a time when the likes of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were already beginning in earnest to depersonalize artistic gestures and subject matter, Pollock, alongside Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clifford Still, were being heralded as the vanguard of heroic and singular forms of artistic expression and the preserve of art’s isolation from mass culture.

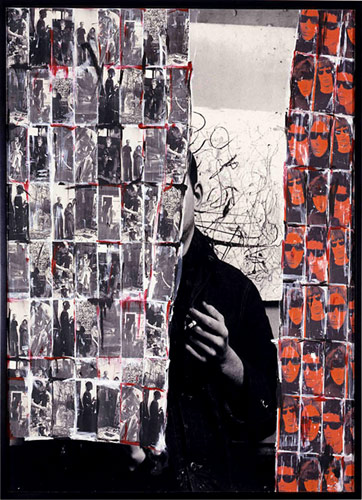

Richard Prince, "Untitled (Covering Pollock," 2010). Collage and acrylic on c-print. Courtesy Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, and Guild Hall Museum.

Johns and Rauschenberg, and soon Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and others, complicated modernism’s claims of artistic authorship and authenticity by turning to popular and often banal subjects drawn from mass culture and producing works that mimicked—and often exploited—commercial modes of production. This depersonalization and mechanization of art’s form and content did more than simply complicate the claims of authorship and authenticity so dear to high modernist aesthetics; it inserted the idea of the multiple into the once autonomous space of the unique, and introduced the plural into the singular in a way that dramatically impacted our conceptual appreciation of these binary terms. What Johns, Warhol, and these other postmodern artists explored—and what Prince’s work can in its own way be seen as a climactic expression of—is that in postwar American mass culture the mark of a moment, a gesture, an image, and a person can be removed from its original context and effortlessly, imperceptibly re-contextualized and reiterated (Richard Prince: “I’ve gotten to know [Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists] through images in books.”[1]).

Jackson Pollock and Sid Vicious both, consciously or otherwise, mobilized the conventional signs of a (still) romanticized countercultural artist-as-rebel struggling against the strictures of consumer culture. Prince’s act of covering in his Covering Pollock series drains the images of Pollock of these modernist myths and allows them to be presented as what they are: photographs marking less a painter and more a sign of modernism’s desires (there is even one image where the center crease of the book is clearly noticeable). Alongside images of punk rock icons and nude models, Prince’s re-use of Namuth’s photos of Pollock, who was himself ultimately performing for the camera, suggests that the modernist invention of forms—art objects, artistic gestures, and artistic personas—has always been infused with certain requisite signifiers that operate wholly in the realm of mass production and mass consumption.

Richard Prince: Covering Pollock is on view at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York, through October 17th.

Richard Prince, "Untitled (Covering Pollock)," 2010. Collage and acrylic on c-print, 47 1/2 x 40 inches. Courtesy Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, and Guild Hall Museum.

[1] “In Conversation: Richard Prince and Lisa Philips, Director, New Museum,” published in Richard Prince: Covering Pollock Exhibition brochure.

Pingback: Another Example of Photo Manipulation: Richard Prince » studio3240.com