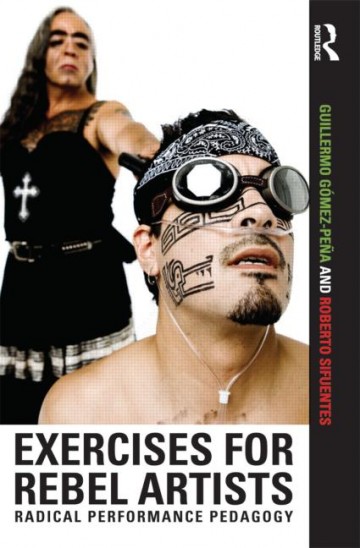

I am on my way to New York, but not before finding Exercises for Rebel Artists: Radical Performance Pedagogy by Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Roberto Sifuentes delivered to my door on my last day at my Chicago address. Gómez-Peña is an original performance art activist whose work combines a very real goal of exploding race, class and gender constructs with an equally real goal of achieving a singular aesthetic. The book is an instructional how-to manual for creating workshops and performances based on the exercises developed within his collaborative group, La Pocha Nostra (of which Sifuentes is a long-standing member). I am not sure that I have ever seen a manual for performance such as this before, with illustrations, step by step breakdowns and documentation of the workshops.

What the book is establishing in 2011, the year of its publication, is that yes, performance art does involve technique. It’s not dance technique, it’s not acting technique, and it’s not directed toward the goal of becoming virtuosic. It’s taking the foundational movement exercises, warm-ups, and techniques centering the body and pairing it with social consciousness to generate radical intimacy. As participants walk through a room with their eyes closed, or hold one another’s gazes for an interminable length of time, or perform tableaux-vivants as ethnic stereotypes (all extractions of exercises that are detailed in Exercises for Rebel Artists), they are breaking down conscious and unconscious barriers to connect with one another and with future audiences. On my last night of attending exhibition openings in Chicago, I was struck by more than one showing of performance, sex, and ritual action. At Intimacies, a group show curated by Lorelei Stewart and John Neff that’s currently on view at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Gallery 400, I spent time with a video by Elijah Burgher, whom I had met on his way to Skowhegan a few months prior [Burgher has also been a blogger-in-residence on Art21 Blog]. Burgher draws from magick and the occult to generate glyphs or sigils that he then draws, paints, and carves into his body in his studio.

Elijah Burgher carving a sigil into his chest as part of a ritual action, May 22, 2011. Image from the artist's Tumblr site, https://havesexwithghosts.tumblr.com.

The artist sites his fascination with ritual and symbol as born out of a queer connection to mysticism through the likes of William Burroughs and Genesis P. Orridge, among others. Although he does not disclose the meaning of the symbols he creates for his sigils, he sees his actions as a means of exposing the body and revealing queer desire to transmute societal shame and violence. After Burgher lights candles, mixes his blood with paint and slowly paints a pattern on the canvas on the floor, he carves the same pattern onto his body and then masturbates until he ejaculates on the canvas. He treats the camera as a silent witness, never making direct eye contact or addressing the viewer.

Detail of sigil ritual action by Elijah Burgher. Image from the artist's Tumblr site, https://havesexwithghosts.tumblr.com.

The video raised questions for me about what might be a turning point for artists of my generation, some of whom are turning to their bodies in the wake of formal approaches to painting, sculpture and the like. Sure, there is a hint of action painting suggested through a surface glance at Burgher’s video, and yet the context and goal of these two types of work are different. Artists such as Gina Pane, Catherine Opie and Ron Athey elucidate a wider perspective on this practice as body art. Perhaps by looking to a historical context in performance, such as that of Guillermo Gómez-Peña and La Pocha Nostra, one might see that Burgher’s work shares many of the same goals and means as that of the performance activist, no matter if it is bound to the studio and is intended for the gallery. With Exercises for Rebel Artistsin my bag, and Burgher’s video in front of me, I noted the auspicious timing and wondered, “What would it mean for young artists to undertake a performance practice with the understanding that a history of radical performance precedes them, and that this history is now beginning to be written and disseminated?”

Maria Petschnig. "Leaves", 2011. C-print, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy Western Exhibitions.

A few blocks away, I arrived at Western Exhibitions to see Maria Petschnig‘s installation. Standing on a taupe shag carpet surrounded by taupe-painted walls, I faced a series of prints of the artist’s body with patterns of material that reference fetish garments with an 80’s punk flair. While there was a familiar quality to the images of the body with fabric cut and stretched, the focus of pattern and shape offset by flesh was revelatory. Leather, mesh, nylon and ribbon were situated as signifiers of sexual display but abstracted from pornographic content. In the corner was a video of Petschnig dressed in different combinations of fetish apparel, watching TV, working on her computer, or standing in the mirror. These scenes had an abject quality about them, as the artist waits and waits for someone or something to fulfill her fantasies. She appears more as creature than sex object, as random parts of her body are obscured to construct an image of a being with perhaps an as yet undetermined purpose and use. Petschnig, like Burgher, uses the camera to record her actions, but never addresses the audience. As voyeurs, viewers witness the artist in her private world of isolation.

Maria Petschnig. "An Evening at Home," 2011. HD video, 7:48 min. Video still courtesy of the artist.

Increasingly, studio practice is defined by a corporeal relationship to space and the media the artists utilize to produce their intended images. In this instance, video provides a window into the artists’ private worlds; however, it is clear that these worlds are meant for public consumption. Of course, the role of the viewer as witness and voyeur makes sense in relationship to ritual and sexual behavior, but can there be more possibilities for encounter? Perhaps if a connection with the viewer is considered in these recorded actions, the works would have the potential to effect the viewer on the level of experience and be changed by watching. This is where pedagogical influences from performance art can serve artists across disciplines, and strengthen connections in the work between the body, time and materiality. There is nothing wrong with the desire to communicate with the body, and embracing performance as form.