Trevor Paglen is an artist, researcher, and writer based in New York and San Francisco. His art practice centers around making what is typically invisible visible—specifically, covert military and intelligence operations in the United States. Paglen travels to remote desert sites to capture reconnoissance satellites in the night sky or hidden military installations. As a result, Paglen’s photographs are aesthetic explorations of his interest in “black sites”—attempts to grasp the abstract questions that these sites pose about the socio-political moment.

Paglen’s visual work has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Tate Modern, London; The Walker Arts Center, Minneapolis; The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Institute for Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, North Adams; the Istanbul Biennial 2009, and numerous other solo and group exhibitions. Most recently, he was featured in a solo exhibition at the Vienna Secession in 2011.

Trevor Paglen. "Dead Satellite with Nuclear Reactor, Eastern Arizona (Cosmos 469)", 2011. Courtesy Altman Siegel.

The following is Trevor Paglen’s reading list, along with his commentary.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (2004)

I have read this several times, at the moment I am looking at it not in terms of the overall arguments but how the collage process succeeds and fails.

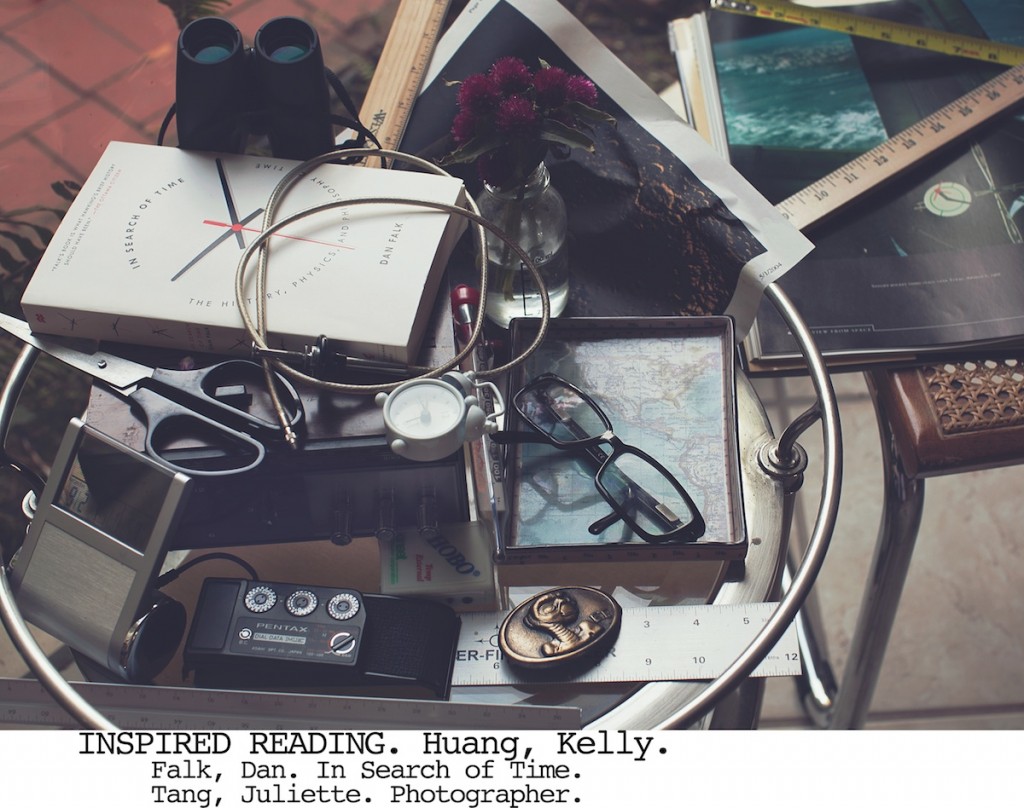

Dan Falk, In Search of Time (2008)

I picked this up at a bookstore in Reno and read it during long exposures shooting dead spacecraft in night skies over the Eastern Sierra.

Graham Harman, Towards Speculative Realism (2010) and Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude (2008)

It seems like all the kids these days are into the speculative realism thing so I am trying to catch up.

Assorted academic articles on “anthropogeomorphology” by Roger Hooke, in particular On the Efficacy of Humans as Geomorphic Agents (2000)

George Lakoff and Rafael Núñez, Where Mathematics Comes From (2000)

I have been reading this for about a year. It has taken me that long to start understanding their argument. I was always terrible at math and had to learn a lot about calculus and set theory to even begin understanding this book. Fortunately, Rafael Núñez is a great guy who is best friends with Teddy Cruz and has become my personal math tutor over Skype and on a recent visit to his lab at UCSD. I love my job.

Kevin Mitnick, Ghost in the Wires (2011)

This is a fun book I read on an airplane last month. It is really interesting to see the depth of Mitnick’s understanding of telecommunication infrastructures.

Carl Sagan, et. al., Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (1978)

The book for the Voyager “golden records”—something like “The Family of Man” meets ET.

Paglen and I spoke over the phone on September 24, 2011 to discuss his reading list and process.

Kelly Huang: It is evident that you have a research-based practice, as your photographs often reveal drones, satellite, and other “secret” military and intelligence operations. Can you share with me your artistic process? Specifically, where do some of these texts fit into your process?

Trevor Paglen: It’s different from project to project. One project always leads to another, for the most part. For example, the CIA creates various infrastructures, and I wanted to understand what those kinds of landscapes look like and how they were put together. Over the course of doing that, I got really interested in how aviation infrastructures work. As a result, I ended up talking to hobbyists who track airplanes. As a part of doing that work, I realized there is another hobby that even fewer people did that was tracking satellites and different types of spy satellites. I kind of put that in the back of my mind and later came back to it and learned how that worked.

It is a very research-intensive practice in the sense that I am always looking for different kinds of information. I try to get as close as I can to primary sources. I spend a lot of time looking, and so much time that what it is that I am looking at almost tells me what it wants to be, in terms of art. I don’t usually set out with a preconceived idea of what it is going to be. I will just learn as much as I can about the ballpark of what I am interested in and something usually comes from that.

KH: You could be defined as many things—a scientist, journalist and artist. Your research interests in geographies and what you call the “black world” of US military and intelligence agencies are really the threads that run through all your work. When you go out into the field to create your photographs, are you also there gathering information as a journalist or scientist?

TP: Sometimes. Here’s the way I look at it—I’ll be researching something and some parts of that research might be more interesting as art projects and some parts of it are more interesting as articles or lectures, even. I am always looking at and trying to understand huge amounts of material. The vast majority of that does not become anything. I am always looking for the moments where I am finding the allegories or stories. So, again I do not have a preconceived notion of what something is going to be going into it.

Overall, with the visual work, I am really interested in what the limits of our own perception are; what are the limits of our ability to understand the world around us; and what do the limits of those perceptions look like? I mean that very literally. For me, those are the questions that tend to show up in my visual work more because I think those are the kinds of questions that visual art is very good at trying to deal with. It turns out that those are some of the oldest questions in art: How do we know what we know? What does that look like? You can take that as far back as you want—to Roman mystery religions and probably even to cave paintings.

KH: You can definitely see that you have a broad interest in experimental geographies, as you call them, but you also have a deep relationship with art history, which is evident in your visual work. Your last exhibition at Altman Siegel included really gorgeous painterly photographs that reference Rothko or the Color Field artists, and there were even references to Muybridge, too.

TP: Ultimately, a lot of visual work, as we know, is asking questions about: What does the world look like at this particular historical moment that we are living in? And one of the many ways to access that question is to look at artists who, historically, were living in times when cultural perceptions were changing, and when quite literally, the world started to look very different, and look at artists’ responses to that. For example, Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed was obviously in the context where machines and forms of communication were dramatically speeding up—going from most of life happening at the pace that you or a horse could walk to the pace that a train could move or electricity itself could move. This was a massive reconfiguration of how humans experienced the world. And for a lot of artists, you can see those reflections happening in their work.

KH: What are you currently working on?

TP: In the spring of 2012, there will be an exhibition of new work in Istanbul that Mari Spirito is curating. Right now, I am thinking of debris as an organizing principle of the exhibition—how the leftover stuff from different institutions and infrastructures influences the future. I have been very interested in time. There are a number of projects I am developing now that address all the different forms of time that we live in at the same time. I know that is a very esoteric thing to say, but that is something that is on my mind a lot these days.