Hundreds of giant, silver, cloud-like, helium-filled Mylar balloons reading “Magic Bullet” float in a white room in the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto. Magic is right. The shiny, crinkling objects of air dance like parts of a mobile rotating above a child’s crib. And “bullet” is also right: the shape of each balloon–a pill–is meant to evoke the anti-viral drugs that artists Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal – two thirds of the famous Canadian art collective General Idea – would have taken for AIDS-related illness. AIDS is one major theme explored in the AGO’s Haute Culture: General Idea retrospective, alongside “the artist, glamour and the creative process;” “mass culture;” “architects/archaeologists,” and “sex and reality.” The 300 works on display take you from bizarre and comical objets d’arts like faux fossils, to hilarious video spoofs on beauty and glamor pageantry, painted macaroni, and a series depicting a trio of neon poodles copulating on black-painted canvasses. Life, including death, it appears, is as dark as it is humorous.

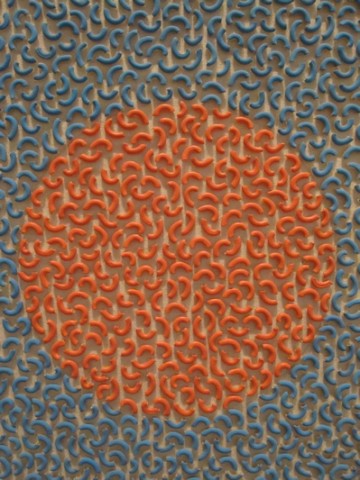

Untitled (detail), 1986. Acrylic and pasta on canvas. Image courtesy VoCA. Collection of Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (Mudam), Luxembourg.

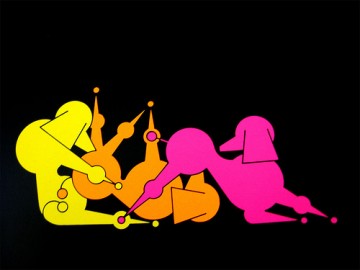

General Idea. Canvas from the series "Mondo Cane Kama Sutra,"1984. Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea; ©Pierre Antoine, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, 2011.

"Mondo Cane Kama Sutra," 1984. Installation view. Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea; ©Pierre Antoine, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, 2011.

General Idea delighted in their sense of humor; case in point: poodle symbolism is everywhere in the exhibit. Operating as a stand-in for “the artist,” the poodle is General Idea’s alter ego, chosen for the banality of the animal and the arbitrariness of sophistication ascribed to it. For General Idea, poodles can have an air of importance about them the way that artists do: not much has to necessarily be there before people are buying into it and once they do, others come to attribute the same sense of value to them, et voila! Suddenly everyone’s a believer. Thus the image of the display dog, preened to make its grand and glamorous appearance, shows itself throughout the exhibit: on flags ironically hailing the artist, on shields and crests, in illustrations, and rigidly presiding on straw in hilarious installations.

"XXX (bleu)," 1984. Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea; © Pierre Antoine, Musee d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, 2011.

Another room reveals three poodles used to paint blue “X”‘s onto large canvasses, suggesting that the General Idea alter ego had to put its whole self into making art work. General Idea were aware that in irony lies mockery and truth, once saying, “We knew in order to be artists and to be glamorous artists we had to be artificial and we were.” Their appropriationist method also extended to playful recreations of recognizable symbols of consumerism; for example, macaroni paintings of well-recognized logos, and renditions of iconic Mondrians. They were not created with homage in mind, but rather they were poking at the establishment of value and status in the art world, and the fame and notoriety that go along with it–an idea they explored most thoroughly with their Miss General Idea Pageant and Pavilion.

The 1984 General Idea Pavillion played with the idea of the exclusivity of the museum by highlighting the spectacle of the unveil. Installations and spectacular General Idea art objects were revealed to audiences not normally privy to grandiose “insider” unveils. Following it, the recurring Miss General Idea Pageant was another faux-event meant to establish General Idea as an art collective. It too had dissolving boundaries and determinants, but loosely; it involved audience-based, scripted and staged series of performances, including at museums. General Idea’s “mythical” and “glamorous” pavillions even subverted the museum’s ranks by narrating the schedule of events to the museum’s director. Elaborate dance performances would take place as though in a talent competition at the museum. They encouraged communal experience through evoking an elaborate awards ceremony. Glamour, art, and influential people: the Miss General Idea Pageant now seems a precursor to the very obvious and unabashed quest for stardom we see played out today. It’s as though General Idea was aware that this “even better than the real thing” mentality would eventually come to fruition with reality TV. In this regard, General Idea seems to have continued where Warhol left off and where perhaps DIS Magazine, net artist Ryan Trecartin‘s clever riffs on “reality,” and the desire for fame continue in the age of the Internet.

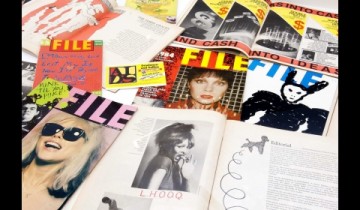

Display of FILE Magazine, 1972-1989. One set of magazines–26 issues. Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea; ©Pierre Antoine, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, 2011.

General Idea also created invitation cards with instructions (many of them reading like those in Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit). Yet, at the AGO, although the ephemera left as evidence of General Idea’s Pavilion and Pagent projects–as documented in General Idea’s FILE magazine, in mail calls for submission, and in photographs–is somewhat interesting. As with all performance-based works, context (time and place) is critical, and it’s hard to get the gist of it in a gallery setting decades after the event happened. The ephemera locked in glass display cases is ironically removed from General Idea’s mockery of the theatralization of the museum. Of course, it is for understandable reasons–the AGO can’t have visitors rifling through the original documents and art objects. On the other hand, the AGO chose to screen the General Idea videos on tiny screens (I’m guessing so as to evoke the original screening method), however, crowding around a small screen with dozens of others at the museum isn’t optimal for viewing. The diversity of media in the exhibition is over-stimulating. That some of General Idea’s original work may even seem sloppily put together by museum standards is fitting; the group existed in part as a reaction to the official decorum of the art world, and curator Frederic Bonnet seems well aware of this fact. And yet, the ephemera, along with General Idea concepts expressed in video, painting, sculpture, installation, and photography, overwhelmingly reveal the multitude of media that the collective worked with, long before “multi media” was common practice.

"Infe©ted Mondrian no. 6," 1994 (installation view). Pierre Antoine / Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea, 2011.

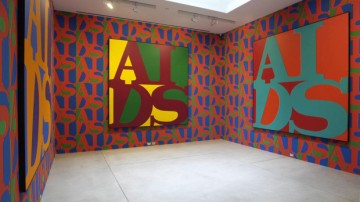

The AGO exhibit suggests that General Idea were not perfectionists, they weren’t concerned with the mastery of a medium or even the fine-tuning of an artistic expression. Rather, they operated with a sense of experiment and more importantly, of urgency. Producing an impressive volume of work and getting it out while it was relevant, made General Idea ahead of its time. In 1969 they mixed commerce and private life when they transformed their storefront living space, opening it to the public to purchase their work. The same DIY concept today has a name, “the pop up shop,” and has since been appropriated by luxury brands and galleries alike. They also created public-access inspired videos called “Test Tube” that remind one of YouTube. Their appropriation of Robert Indiana’s famous LOVE painting of 1964 into the General Idea AIDS logo in 1987 recalls the late 90’s-present graffiti and stencil artists for whom simulacra is modus operandi. If an artist is only as relevant at the time of his output as his ability to control the dialogue surrounding it (and General Idea did this), it defines its future.

"AIDS," 1987 (installation view). Silkscreen wallpaper, various dimensions. "AIDS," 1988 (installation view). Acrylic on canvas. 243.7 x 243.7 cm. Gift of Robert and Lynn Simpson, 1997. Photo by Carlo Catenazzi/Image courtesy the Estate of General Idea and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

The work that left the greatest impact on me at AGO however, was the chilling “One Year of AZT/One Day of AZT,” a sterile, white cube filled with neatly-arranged identical vinyl pills, representing mass-produced medication for one year’s dosage of treating an AIDS patient (the image pictured above is not the same as that on view at AGO, because an image from that exhibition was not available). Only one-third of the General Idea collective– AA Bronson–is still alive today, while the other two members died from AIDS-related illnesses in 1994. The AZT installation was made in 1991 when all three members were still living and working together, two with illness, and while Bronson took care of them.

"Playing Doctor," 1993. Image courtesy The General Estate of General Idea. Collection: Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography.

The collective literally worked on creating art together through the period of two of the members’ illness. Their art during the illness period was as self-referential as it was social and political. It seems unfathomable that the collective would continue working through a period of suffering health. Yet, for General Idea, the compulsion to create work must have been paramount. I happened to visit the exhibit with friends; two professional artists for whom collaboration with other artists has always been crucial to their practice. One friend left the AZT installation speechless with tears welling in his eyes. How many art collectives work together until death? The profound and contradictory work of General Idea surpasses the confines of the physical manifestation of the works. General Idea ended with the deaths of two of its three members. But the name “General Idea” is fitting for a collective whose work continues to generate more ideas long after it has ceased to exist. A retrospective at one of Canada’s most prestigious museums will hopefully reinstate “General Idea” within the common vernacular, not just internationally–where the collective has been legendarily known for some time–but now, finally, in Canada too.

Pingback: Calling From Canada | Haute Culture: General Idea Retrospective at AGO - 1-954-270-7404