Dave Hickey has called us out. “It’s corny,” the critic told the New York Times, referring to Pacific Standard Time, L.A.’s current, Getty-funded initiative to canonize L.A.’s post-war art through a hundred or so thoroughly-researched exhibitions hosted by over sixty institutions. “It’s the sort of thing that Denver would do. They would do Mountain Standard Time.”

L.A. did it first, L.A. is an art capital—I’ve heard some variation of this again and again over the past month. I’ve never flinched when people say New Orleans invented jazz or New York owned the Ab-Ex movement, but it’s different when you hear such praise, such broad praise, about your own city, in your own city.

On one hand, the party’s been fun so far, and some of the art’s been a revelation—like Eleanor Antin’s paper doll hijacking video, and Betye Saar’s mystical installations. On the other hand, I feel sort of like it’s Fourth of July all the time, only patriotism has been replaced by regionalism, or like I’m at the Château de Chenonceau in France in 1560, watching the country’s first-ever fireworks extravaganza and feeling like we invented gunpowder. At the Getty’s nighttime exhibition opening two weeks ago, lights projecting the sun-shaped Pacific Standard Time logo danced all over the complex’s many layered buildings like fireworks and a booming voice walked guests through SoCal’s recent art history. At the reception, you could graze food tables themed after every decade—I took mashed potatoes from the 50s domesticity table. All of it was uncomfortably spectacular.

But some of the work in the Getty’s show, the centerpiece of PST, is uncomfortably spectacular, too, and, I suspect, still relatively unknown by those outside this city.

Peter Voulkos’ bulbous vessels; John Mason‘s ceramic wall pieces:

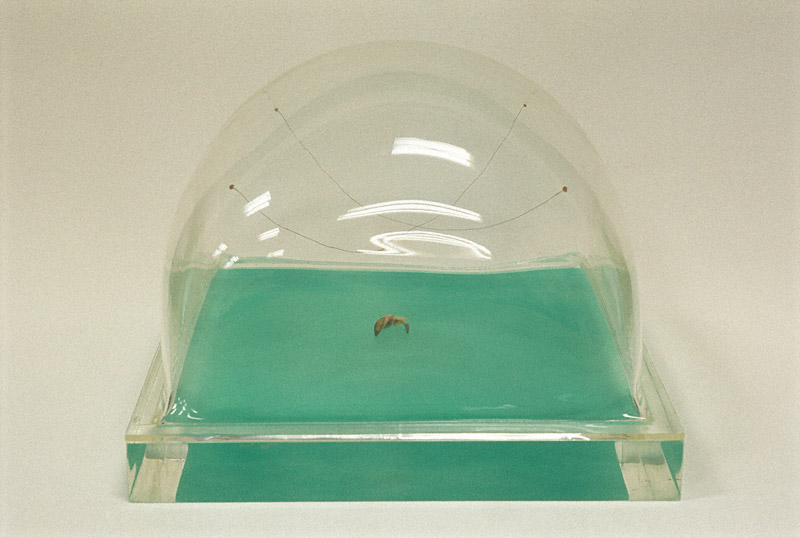

Robert Graham’s funny, sunny dioramas;

Robert Graham. "Untitled," 1967. Polyurethane resin. Collection of Ed Ruscha. © Estate of Robert Graham

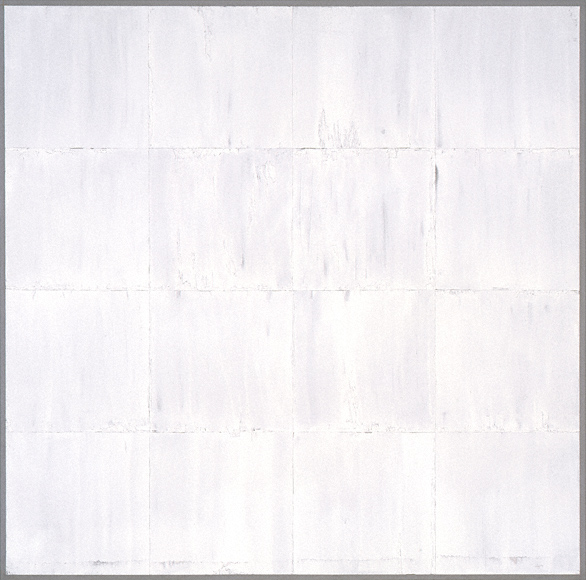

DeWain Valentine’s smooth resin; Mary Corse’s impossible-to-photograph, glass-encrusted, white-on-white paintings;

Mary Corse. "Untitled (White Light Grid Series-V)," 1969. Glass microspheres in acrylic on canvas. Permission courtesy Ace Gallery and the artist.

and of course, Hockney’s splash paintings, known outside L.A. certainly, but not fully appreciated unless you’re standing in front of them, soaking up their incredible, confident precision.

So what to make of PST? It’s embarrassing for sure. Regional boosterism has to be, especially since it exposes fear of marginalization, which is the neurotic kind of fear that can persist long after marginalization has more or less receded. But maybe the embarrassment is worth a few good shows? I’m not sure.

My favorite Los Angeles art lore story is from David Hockney, who moved to California in 1963. The first night he stayed in L.A., he checked into a beach front Santa Monica hotel. He saw lights in the distance and walked toward them–he didn’t have a car, and didn’t know how to drive anyway–thinking it must be the city. After walking two miles he got there and found a big gas station. Not a city at all.

That’s the best thing about Los Angeles and its art, that things are spread out, confusing, and hard to find. It’s partly what made historicizing L.A. art difficult and, despite all the aggrandizing PST lingo, it’s something PST has embraced. There are shows beckoning to you from all over the region–Orange County, Pomona, San Diego, East L.A., West L.A., downtown, etc.–and it’s nearly impossible to visit each and every one. Even when you do, they’ll only be a teaser, not the real city at all.

And that’s the last I’ll say about PST (in this column, at least).

Pingback: Money/Market | Art21 Blog