I don’t live in Chicago anymore, but I frequently visit. Over the past summer I was invited to a housewarming party for friends who had rented a large loft space on South Michigan Avenue that was easiest to reach by taking the Cermak-Chinatown CTA Red Line. On the way, I passed the Hilliard Complex housing project and realized that even though I had seen these buildings many times before while on my way to eat some Dim Sum or see a White Sox game, I had never associated these projects as works by Bertrand Goldberg. Currently Goldberg is experience a type of second-Renaissance of appreciation in the city, with two retrospective shows at The Art Institute of Chicago’s Modern Wing as well as at The Arts Club. The extensive display of drawings, models, furniture, designs, and other ephemera shown from The Art Institute’s dedicated collection provides a dynamic narrative of Goldberg’s development from Bauhaus disciple into a significant figure in architecture, engineering, and urban planning.

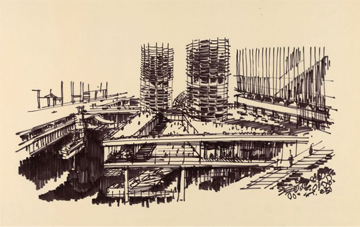

The daunting scale of his pursuits and passions for exploration of the urban landscape propelled Goldberg into national recognition during the late 1950s, when many of his most well-known projects were either being completed or announced. His work included single-family homes, commercial projects, and several municipal or institutional works. During his 60 year career Goldberg completed over 30 finished buildings, the bulk of which exist in Chicago. He had great faith in the exciting power that comes from living in close proximity to one another, and claimed that “most men like the action that comes from living together. We like the market place, we like the forum. We like the social and mental heath that we generate when we rub against each other. We like cities.”

This undaunted enthusiasm for the experiment that is the urban environment is lucidly explored in Goldberg’s most famous multipurpose “cities within cities.” He wanted to minimize the commute of a city, the distance that travel creates amongst its citizens, and to treat every structure as its own microcosm of activity and shared cultural community. A decisive turn in Goldberg’s career occurred in the 1960s, when his designs and perspectives began to borrow from the ideas of Renaissance humanism. As the exhibition materials on Goldberg’s work published by The Art Institute suggest, the types of projects designed by Goldberg took a radical turn away from single family homes to projects that spoke “a common vocabulary… of collective participation and civic responsibility.” It seems no mistake that this type of humanistic dedication to the progressive development of the lived-in and built environment of a city would occur in Chicago. I hope that the following anecdotes attest to the brilliance that Goldberg imparted to the City of Broad Shoulders.

***

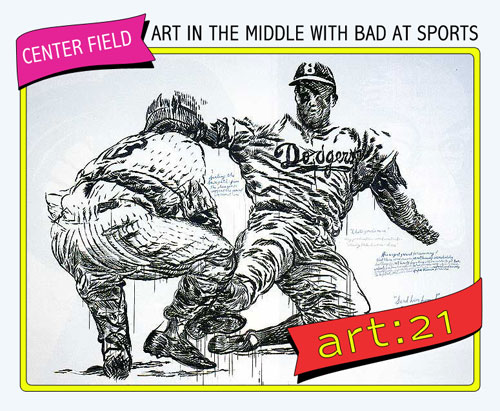

Bertrand Goldberg. Marina City, Chicago, IL, Perspective Sketch, 1985. Courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago.

When I first came to Chicago in the winter of 2003, I already understood that Chicago was one of the great architectural epicenters of the Western hemisphere. Between my former high-school sweetheart’s architect father, and my own mother’s recollection of her experience of riding the L as a Baby Boomer teenager, I had been instilled with the knowledge of the extensive built environment that played an integral part in the history and contemporary cultural climate of the city. Even with these surrogate memories implanted into the architectural expectations of my first visit to the city that would soon become my second home (and first true urban romance), I was still overwhelmed with the variety of skyscrapers, brownstone storefronts (and the apartments “living-above-the-store,” as Goldberg’s mother eloquently described), museums, and residential structures that speckled the flat midwestern lake side.

I was particularly shocked to find, almost by complete accident while on my first stroll around downtown, the twin towers of Marina City, their corn-cobbed faces looking down at me–a sight that many would recognize from the cover of Wilco’s album Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. I stood at the northwest corner of State and Wabash looking across the reversed river to the balconies and exposed parking garages that give Marina City its signature ridges and ribs–an engineering triumph of its time. The strangeness of seeing a building working against the angularity and rigidity of works by Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies Van Der Rohe that came to mark the Chicago suburbs and skyline was instantly welcomed with an unfamiliar glee. The building itself was designed in such a way as to optimize the modularity that Modernism had perfected–it was constructed at the incredible pace of one floor a day–but used concrete and earthen hues to challenge the cold steel that also came with this mobility.

One could argue that the entire structure was very much a direct jab at the architecture of its neighbor, The IMB Building at 330 North Wabash. The curvature of Marina City’s facade alone points to Goldberg’s detestation for right angles and their oppressive implications. The investment in this challenge, of how to make structures that were engineered for both economical efficiency and world-class design, is evidenced in the extensive research that Goldberg’s office conducted during this period. As Goldberg expressed in The Chicago Architects Oral History Project (in the context of a discussion on the publications that his office published on urban planning and domestic high-rise architecture), this devotion stemmed from “always feeling as if there is more to be done.”

My fascination with Marina City has never yielded an interior visitation, but I have frequently stopped on my bike ride home along Wacker Drive to admire the towers. During the periods when I’ve lived in Chicago, I have walked around underneath the site as well as viewed it from afar some seven or eight times. A perpetual fascination with the site and engineering of this monument–one that extends beyond Wilco–has remained in me, from that moment of first visitation well into this past summer, when a friend from out-of-town stayed in a hotel across the river. We were having a nightcap on a street-level patio, and I looked over his shoulder to point out where the famous car free-fall occurred in the movie The Hunter some 30 years before. On that night, we looked up to see the balconies and windows lit up with decorations, forgotten christmas lights, and other flashing bulbs and sparkling furniture, imagining what it would be like to live in such a remarkable structure.

***

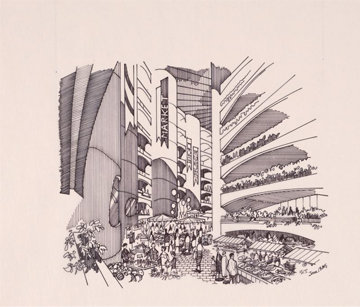

During my undergraduate studies I went to visit a friend living in River City to play music, watch claymation, and generally relax before immersing myself back into the spring semester. I was living in a tiny apartment on the near north west side at the time, and had barely ever ventured to the South Loop for anything besides the occasional show at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. I distinctly remembered my friend telling me to get off at the Clinton stop (even though I believe the LaSalle stop to be closer). I’d never gotten off on this stop before, even though I’d passed it countless times while on my way to the West Loop or Oak Park. Getting off the train and coming above ground found me underneath Congress Parkway, right next to the south branch of the Chicago River. I found I had to cross the bridge at Harrison in the midst of a typical Chicago February gale that made for a disorienting and troublesome trek. I hadn’t initially known that my friend was living in an architectural treasure, and just had the 800 South Wells address with which to navigate my blustery walk from the Blue Line stop. However, as I arrived at the open field of River City’s grounds and looked south and upwards, to the distinctive semicircular serpentine structure of Goldberg’s mixed-use mid-rise adaptation of a much larger (230 acres) project, I knew that I would be in for a memorable afternoon.

I entered the massive lobby and although my visual memory of looking into the cavernous space is hazy now, I remember experiencing the weight of the concrete that encased the fairly dim corridor that led to the front desk. This bodily sense was important to Goldberg; in a publication he wrote for The Museum of Science and Industry, he stated that his research showed “a profound need for communication – not just communication by telephone or the written word, but by body language.” At first I felt small–maybe in part due to the chilling walk from the train–but later, I was warmed by the presence of the space, and my individualistic place within the community I had entered.

Continuing on past the empty welcome desk and navigating the hallways to my friend’s apartment put me in the remarkable nine-story chamber that snakes along the building’s interior. I gaped upwards into the canyon that this space makes between outward facing apartments, a passage so spookily empty during my visit that my entrance alone created a cacophony of reverberated rattling. I must have stood at that entrance for some time, admiring the impossible airiness of the concrete and glass atrium, since my friend called and asked if I had gotten lost. Although I reassured my friend that I was only a few steps away from his door, I should have honestly answered that I had, in fact, lost myself in that moment.

Upon entering the actual apartment, I was surprised by the lack of care that my friend had taken in furnishing the roomy accommodations of what was billed as an efficiency unit – even if now I recall that there was a separate bedroom. This observation of the apartment’s unique quality was part of the design that went into River City. The 22 different floor plans that Goldberg intended for this structure were aimed at highlighting an “interest in the individual rather than on the abstract society.” This late philosophy in Goldberg’s lectures and writings points to a readjustment in wanting to understand the desires of a community based on interpersonal needs.

I’m sure that part of the cramped feeling I had when entering to room was due to the unit’s over-occupation. My friend shared his room, and two other people slept in the living room, which was sectioned off by sheets and movable partitions. Although this clutter clearly did not suit the living arrangement that Goldberg (and most likely the landlords) intended, I’d venture that the ingenuity of my friends in finding a way to live cheaply downtown was satisfying the desire for urban adaptability that Goldberg sought to achieve with his work. I couldn’t resist immediately asking my friend to go out onto the south-facing balcony to admire the industrial corridor that still clung to the south branch of the river. Reluctant to let in the cold from outside, my friend eventually obliged my request and joined me for a cigarette. We smoked in shivering silence as the south side chimneys plumed their steam and heat into low clouds that had already started to dust and accumulate onto the cement courtyard below. In that moment of looking out from the terrace of one of Goldberg’s last built projects, I gained a newfound and immense appreciation for the work of a man who contributed so much to the urban fabric of Chicago.