Exterior view of Bunker Berlin. Courtesy The Boros Foundation.

Located on a relatively quiet street in fashionable Berlin-Mitte stands a hulking, imposing building known as Bunker Berlin. With its stark concrete façade, the daunting structure contrasts sharply with the neighborhood’s quaint bookstores and boutiques and the medley of modern architectural styles that surround it. Unlike those of its sleek neighbors, the stout, two meters thick exterior walls of this incongruous monolith are deeply scarred—pocked with bullet holes and disfigured by mysterious gouges, in places so deep that the rebar of the reinforced concrete lay exposed to the elements. From the outside there is little indication that this formidable structure houses The Boros Collection of contemporary art and offers one of the most memorable experiences to be had in Germany’s capital city. For unlike so many other contemporary art collections set in industrial looking buildings with an interesting historical past, in Bunker Berlin the history of the structure itself is in intimate dialogue with the art contained inside. And what an extraordinary history it is.

Built in 1942 by the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft (the national railway under the control of the Reich), Bunker Berlin originally served as a civilian air raid shelter—unusually constructed above ground due to the geological limitations of the area. A look at the interior wall plan of the square shelter reveals a carefully and meticulously symmetrical design, based in part on the Italian Renaissance master Andrea Palladio’s Villa Capra outside Vicenza, Italy. In Nazi-era Berlin, however, Palladian precision and symmetry served not the humanist values of the Italian Renaissance, but rather the expedient movement of crowds into and around the building’s interior during Allied bombings. Intended to accommodate up to two thousand people, the bunker often protected several times that number.

After the war the five-story, eighty room bunker saw use as a prison by the Soviet Army and as a warehouse to store fruit, and after reunification became home to one of the most infamous night clubs in Europe, the dense labyrinth of rooms becoming the site of fetish, fantasy and thumping techno dance parties throughout the 1990s. And as much as its outside walls bear the visible scars of Berlin’s dramatic history, the bunker’s interior rooms retain the vestiges of its layered history—in fading graffiti that hint at the bunker’s legendary roll in Berlin’s fin-de-siècle techno scene to more sobering wall markings, including glow-in-the-dark signage originally used to help those sheltered in the building navigate the maze of rooms and staircases during air-raid blackouts.

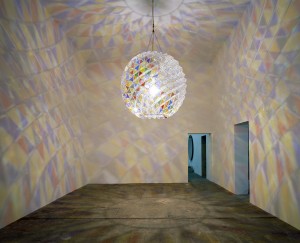

Olafur Eliason. "Berlin Colour Sphere," 2006. Colour-effect filter glass, metal, light, steel. Courtesy The Boros Foundation.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Sammlung Boros is how many of the works on display evoke rather than veil this incredible and complex past. With several of the works site-specific and many of them installed by the artists themselves, the art repeatedly draws the viewer’s attention to the unique history of their surroundings. Olafur Eliasson’s beautiful Berlin Colour Sphere (2006), for example, hangs from the ceiling of one room like psychedelic disco ball, casting a kaleidoscope of colors onto the walls. And if at first Berlin Colour Sphere’s resplendent light and vibrant colors seem to be little more than a formal transformation of an otherwise bleak and even claustrophobic environment—a purely optical experience—one can almost hear the thumping dance beats from the 1990s echoing through the labyrinth of concrete rooms while standing before it.

This subtle invocation of history is evident in another work by Eliasson—Christian Boros has one of the largest private collections of the Icelandic artist’s work—titled Vortex for Lofoten (1999), which consists of a large Plexiglas tank filled with water, which is set in motion by pumps to form a perpetual standing whirlpool. This mesmerizing installation references the Maelstrom, a legendary tidal phenomenon that exists near Lofoten Point in the Norwegian Sea, but the violence and turbulence associated with the natural phenomenon also evokes the bunker’s own turbulent wartime past, one perhaps encapsulated in the common phrase “the maelstrom of war.”

Monika Sosnowska. "Untitled," 005/2008 (partial installation view). MDF and black lacquer, dimensions variable. Courtesy The Boros Foundation and Johannes Vesper.

Nearby stands a daunting black structure that sprawls across two different rooms—an untitled site-specific installation by the Polish artist Monika Sosnowska made of wood coated with piano lacquer. An opening in Sosnowska’s colossal assemblage draws visitors into a narrow tunnel that winds through the bowels of the piece where, once inside, they must fumble their way through in near total darkness until they finally emerge in another room on the other side of the structure. The journey through is visceral and disorienting—an experience that can surely only approximate the uncertainty and anxiety that must have been rife in these same rooms during air-raid blackouts over half a century ago.

Anselm Reyle. "Heuwagen/Hay Cart," 2001/2008. Found object, lacquer, black light, dimensions variable. Courtesy The Boros Foundation.

In the middle of another room stands a simple, decrepit hay cart, a work by the German artist Anselm Reyle. Painted with a neon lacquer finish and displayed under a black light, Reyle’s hay cart radiates an eerie yellow-green glow. While Reyle’s transformation of the found object is relatively minor, Heuwagen/Hay Cart (2001/2008) summons forth multiple aspects of the bunker’s complex and layered past—its role as a warehouse for foodstuffs and as the site of psychedelic dance parties—while simultaneously referencing the phosphorescent paint of the bunker’s glow-in-the-dark wartime signage.

One cannot walk through Bunker Berlin without also admiring the work of Jens Casper, the architect who specializes in bunker structures and who, with an impressive economy of means, subtly opened up the building’s dense and confining interior spaces to accommodate some of the larger works in the collection and to create a slightly more suitable viewing experience. This is not to say that visitors can forget the presence of the three-meters thick concrete ceiling overhead and stout walls on every side. To the contrary, Caspar’s deft architectural interventions assure that the visible signs of the building’s original purpose, its obdurate presence and its complex past remain evident. And this in the end is what makes visiting The Boros Collection such an extraordinary experience, as each work interacts with the bunker’s space and history in its own unique way, serving to draw attention to the important palimpsest of history that is Bunker Berlin.

Olafur Eliasson. "Room for all Colours," 1999. Projection foil, light bulbs, color filter foil, control unit. Courtesy The Boros Foundation.