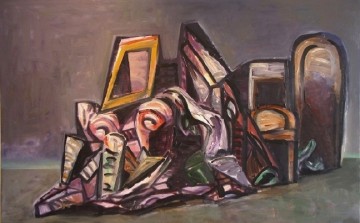

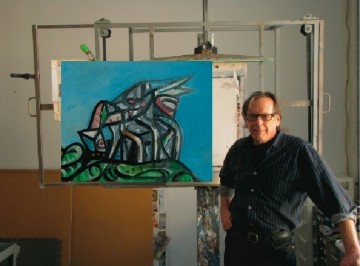

This past summer, San Franciscans were treated to an art smorgasbord from Paris’s Banquet Years, before the Great War. A Picasso exhibition came to the de Young Museum, and an exhibition of the Gertrude and Michael Stein collections came to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Cubist faceted planes were everywhere, and artists who had been taught to dismiss Picasso as irrelevant (inconceivable to earlier artists!), got a belated lesson in art history—assuming they went. Painter William Harsh certainly did, because he reveres “old Pablo” as “a freak or a monster of nature” and “the kind of genius that only comes around very infrequently, every five hundred years or so.” Recently I visited Harsh’s studio in the small port city of Benicia, north of San Francisco. While his recent works are better than ever (with ambiguous creatures reminiscent of Theo Jansen’s walking sculptures now emerging from the Surrealist junkyard wastelands), a review is not the subject of this article; Harsh’s insightful comments, as we chatted over wine on his backyard patio, are informed by his forty-year study of Picasso, Max Beckmann, Giorgio di Chirico, his former teacher, Philip Guston, and many others. In 2003 I cited Guston’s Old-World drinking ritual in an article:

Musa Mayer likens her father’s all-night chats with friends [including the author Philip Roth] to the Russian men’s custom of “drinking vodka, brooding, reciting grievances,” Razdirat’ dushu, to “tear out” or “bare one’s soul,” (And of course Guston’s kvetching with Roth would have produced such literate philippics.)

While my conversation with Harsh was jocular rather than lacerating, the issues raised are worth considering in our current cultural climate. Excerpted below are a few of Harsh’s passionate, erudite, ironic, self-deprecating comments about painting, art history and the mystery and melancholy of esthetes, stumblebums and holy hermits alike.

“I am interested in painting because it seems to feel like the right medium —and it has for a very, very, very long time—for what I am groping and struggling to say. … Anybody who is visually inclined …is going to see that the most profound and sophisticated repository of visual images is contained within the whole tradition of painting…. Painting can express certain things that other media can’t, and no doubt other media can express things that painting is too limited to do, but I am definitely a painter…. I have chosen to go deeply into that.”

“My thought with painting, with any profound work of art, is that the real idea is to have you speechless—with being moved so that you’re speechless…”

“I was stunned by … how beautiful the frescos [photographed in a Norman cathedral in Palermo, Sicily] were. These are eleventh-century, two-dimensional, fresco-like narratives of the Old and New Testament… I realized that in the eleventh century, these nameless artisans who were making these pictures were not only as sophisticated visually as we are in our hubristic 20th and 21st century, but they surpassed us, the level of abstraction and visual sophistication … in addition to the tremendous depth of feeling in these anonymous frescos that I’d never seen before—it was quite stunning, and very, very moving. And the moving part was contained in how the forms were constructed. I mean, it’s the same old Bible stories, the Old and New Testament. I don’t even know half of them or can’t remember what happened to Saint So-and-so, but they’re wonderful, and I took great inspiration from that. It made me want to paint and to continue painting, to measure up to these guys, these anonymous guys.”

“To me any art form is at bottom a kind of visceral experience of emotion… (That’s not to suggest that there aren’t ways and manners in which the intellect mitigates and modifies that.) …Generally speaking, you’re hit in the gut, and as an artist you can appreciate the intelligence with which the form is constructed, but it’s an emotional experience primarily… I am suspicious of the idea that an artist has an idea and then he sets out to find the most “appropriate” way of explicating or illustrating or rendering it. I think that suggests a gap between means and ends, between emotion and intellect that suggests a gap between form and content. And for me all those three categories have to be unities, or the artist struggles to make them into unities.”

“Ideally, art wants to bite everybody on the ass on some level and hook them. And then maybe, if you have enough curiosity and you’ve been bit enough, hooked enough, then you do the work it takes to look at more difficult art.”

“Oddly, I did see some reference to a new Art News magazine cover about young artists discovering Picasso and there was some awful pastiche of him by somebody. Apparently he’s hip again! I swear I saw this a few Art News issues ago, or some other magazine. I don’t know why a whole generation would want to just ignore probably the most astounding century of art since the Renaissance. I don’t quite get that. Are we so focused on the moment and so inside our Angry Birds games that we can’t even imagine that we have a past that nurtures us and nourishes us? And the past is very recent, actually. And [it’s] a past of geniuses, too—that’s the other thing.”

“I’m much more interested in the mystery of the objective life of forms and their expression and how they give poetic expression to the mystery of life. To me, the whole notion of career is so “anti” that. I’m not saying that artists should not have a career—I have one—but I don’t think it should be the pre-eminent thing. If you’re engaged with an art form like painting, it is an all-consuming mystery. It’s a kind of devotional practice. Money or career or reputation just simply has nothing to do with it. Sure, it’s nice when you sell a picture and you have a show, and it’s nice to be seen, and to be able to communicate with people, but it’s certainly not what motivates me…. After forty years of doing this, I haven’t stopped yet. I do expect … of serious artists that they are committed to what they do; otherwise why should we take them seriously?”

“Things pour out of Picasso. He’s one of three or four great visual minds of the twentieth century. I think of him as a kind of Moses, a form-giver coming down from Sinai, repeatedly, over and over and over again.”

“I put myself up against Picasso and Guston and other artists whom I admire tremendously.”

“Novelty and originality are two very different things.”

“I don’t want to give the impression that I think that art comes only from on high. Real art can come from the damnedest place. I like the barbaric yawp [quoting Walt Whitman] of insurgent art because I think of the great modernists as that too…. There is so much … Insurgent and barbaric yawpishness in Picasso and even in Matisse! I’m always looking in younger artists to see that there, that barbaric yawp part that’s so vital and that comes from the most unexpected quarters.”

“There are many, many different legitimate approaches to painting, some of which are far more cerebral, and some of which are perhaps more emotional or visceral or kinesthetic or tactile, My taste tends toward the latter, but I am a great admirer of the others as well, for example, Magritte…or di Chirico, another Surrealist. These are not paint-throwing, visceral guys; these are highly cerebral kinds of painters. There’s room for that. There can be many cathedrals. I don’t see why one has to remain within one pond or another…. But yes, I am built, I am wired to be in the school of heavy drawing, heavy tactility, heavy paint. I guess I’m more or less an Expressionist if that term still obtains….”

“One of my favorite quotes from Picasso… ‘The kind of painting I like is the kind you can drive a nail through.’ … Physical, clear, no question…. You nail it, you nail it, it’s like artillery, to the right, to the left, you get it…. Picasso is a great engineer. He is a great nailer, and he just wants to nail it in the right place. Guston was like that, too, It’s an ethical position as well: the correct and just distribution of forms.”