So, this morning I’m off to sunny Savannah, Georgia, for SECAC (the Southeastern College Art Conference) to present on some of the ideas I shared at the Now Museum earlier this year on radical museum education practice. I’ll report back in my next post at the end of this month: from the airplane snacks, to whether or not sleeping eight people (read: cash-poor grad student presenters) in a two bedroom historic Savannah home is a workable plan.

Hey Wall Street, your parents called. They can't afford to make your student loan payments for you anymore. Good luck with that.

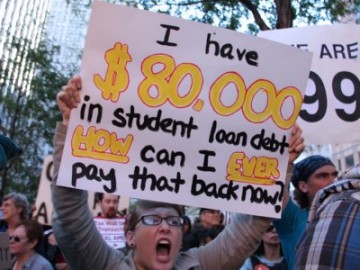

As I think of the artist-educator interventionists of the 1970s, I’m also fixated upon the current practices of contemporary occupation, from the Arab Spring to #OWS. So much, from so many different perspectives, has been written about these heterogeneous protests and their polymorphous demands, ideas and cries. The things we know: the major targets are corrupt administrations (namely banks and political institutions, dictatorial or otherwise) and their suffocation of disparate populations (who are agitating on far-ranging issues, from the right to democratic elections to foreclosures and student debt). Solutions have been posed, and enacted: governmental overthrow; civil war; occupying public spaces; peaceful protest; organizing labor.

The thing I’m less sure about: what works in practice for those of us in graduate school? The Open Enrollment column is about discussing graduate life in the arts. What do we do in this moment? While the theoretical discussions of what’s happening down on Wall Street or in Tahrir Square have been rich and necessary, the most enlightening conversation I’ve had to date on the subject of the immediate protests in New York was with one of my undergrad students at Baruch. She supported the strong dissatisfaction with mounting student debt, precarious job prospects, and the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, but would never go down to Wall Street to join in because “I work two jobs to go to school. I have kids to look after at home. I don’t have time to protest, and nor does anyone else I know who actually has the problems “they” are protesting about.”

Her conundrum, her sense of shared purpose and simultaneous disassociation, is where my question for this post originates. It’s a rising sense of conflict that I’ll share in hopes of being persuaded to a more nuanced position by anyone reading. The students I teach are, for the most part, directly affected by the serious issues that those camped out on Wall Street, or protesting in Oakland, or elsewhere are making visible through their persistent presence. These students tick many of the following boxes: they are first generation to college, from single income households, and work multiple jobs to make their state school tuition. They go to class at night, juggling parental duties with their homework. They feel lost at times because they didn’t get as much attention to the fundamentals of writing or math at high school as they might have hoped for before entering undergraduate life. They speak English as a second language in jumbo classes where teachers are overwhelmed and under-resourced. These are gross generalizations, but they form the greater backdrop of my teaching experience so far.

And this is where my question comes in. Given this picture, why would anyone choose a city or state school if they had other options? Sometimes, you make that choice because it is the only option presented. Sometimes it’s the best option (I got to pick from Edinburgh, Glasgow and St. Andrews, all tuition-free for a Scottish national). In the case of my grad school, it’s about joining a community where you respect the mission, even while you recognize the flaws of the institution and its administration (and, if nothing else, I think the protests have been highlighting the anger directed at the individuals and institutions that have egregiously strayed from their missions to protect, to serve, to act in beneficial manners to the communities to which they answer). While the call to forgive student debt is persuasive, there’s a flip side to that coin that often gets dropped from the discussion. Why aren’t we asking why the heck it’s ok to charge 50K per semester in the first place, and recognizing that the marketplace of higher education is as slimy as the corporations we’re protesting or the politicians we want to hold to account. So my question for this post regarding something we can do is this: can we make a meaningful political statement to support egalitarian educational opportunities by choosing a city or state school to attend or to teach in?

It’s just an idea, but if we’re heeding the call to remove our money from the major banks and move to a credit union (hello Municipal Credit Union, I’m your newest customer!), surely we should also be taking our intellectual capital out of the university institutions that charge exorbitant tuition. We have another opportunity to put our money where our mouths are. As I mentioned in a previous post, when it came down to it I only applied to one graduate school, and for a very specific reason: along with their outstanding professors, CUNY’s mission –“to educate the children of a whole people” – really mattered if I was going to commit five to seven years of my life and career to one place. It’s tricky. I just went to hear Jerrilynn Dodds, Dean of Sarah Lawrence, give an amazing lecture on Islamic Art at the Met Museum last week. Do I wish I’d had her as my teacher at some point? Hell yeah. Would I be willing to pay what it costs to go to Sarah Lawrence? To send my kid there? To participate in something reserved for a very special few? By pursuing a PhD, am I doing that anyway? Those are much tougher questions. (As an aside, Jerrilynn Dodds used to teach at CUNY).

Are they "yours" or "ours"? LIke choosing our banking institutions and our schools, heck, our food sources too, we need to become more astute consumers across the board.

I know I come from Scotland where the higher education system isn’t as much of a broken, money-grabbing free-for-all as it is here (although the UK is fast catching up, with protests scheduled for today) but surely, if we’re looking for things to do after we’ve all ditched our banks, we have it staring us in the face. Educational choices don’t just add up to years of personal debt. Like the increasingly grotesque internship system (love my experiences, hate the institutionalized rape of students by “for-credit” internships, and beginning to realize with horror their symbiotic relationship), choosing a school impacts a whole ecosystem that needs systemic change. If we keep supporting colleges with outlandish tuitions demands, are we feeding similar beasts as the banks? By directing our intellectual resources, our resources as emerging teachers, or our spending power as students to city and state institutions that don’t make a mockery of tuition, can we amplify the statements being made in Zucotti Park and by my student at Baruch? Could that be the beginning of a truly collective action that can benefit disparate yet connected constituents? Or is it every man for himself in higher education? Aka, business as usual on Wall Street.

How do we fix the issue of the rotating adjuncts that service said public institutions and advocate for them? For the unpaid internships we thrust our students into? The rising costs of city and state education? Are there really any practical solutions? Discuss.

Pingback: Open Enrollment | A History Lesson | Art21 Blog