Asco. "First Supper After a Major Riot," 1974/printed 2011. Photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr. Courtesy Harry Gamboa Jr. Image via LACMA.

When I moved to LA from Northern California, my Bay Area friends accused me of taking up with a city that was historically cultureless and apolitical. If Pacific Standard Time–the year long collaboration of 60 cultural institutions throughout Southern California–does not seem to protest too much, it might actually manage to address both grievances. Pacific Standard Time promises to represent every major L.A. art movement from 1945-1980. But rather than explore aesthetic movements, many of the exhibitions parse LA’s sprawling cultural history through the lens of political and social activism.

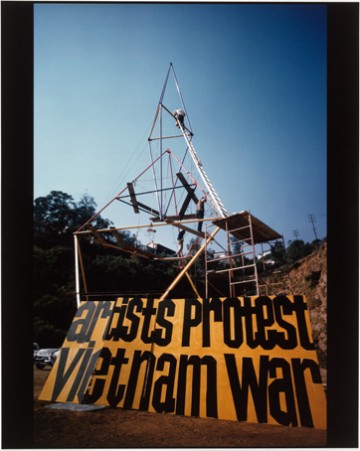

Greetings from L.A.: Artists and Publics, 1950–1980 at the Getty explores the ways in which broader activist movements “mobilized artists to take their messages to the streets,” and features a vast array of prints, fliers, posters, and remnants from artists engaged in protest—from demonstrations in front of the Ferus Gallery, to photographs of Susan Sontag at the Peace Tower installation in Los Angeles, to old exhibition announcements for politically-engaged artists such as Vija Celmins and Judy Chicago. Peace Press Graphics 1967-1987: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change at the University Art Museum at Cal State Long Beach features prints made by the LA artist-run alternative Peace Press. MOCA’s Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974 – 1981 contextualizes its exhibition by confronting viewers with the text of Nixon’s resignation speech. According to curators, the show delves into the transformation of California’s art scene in response to a “collective loss of faith in government and other institutionalized forms of authority.”

Artist Peace Tower installation, 1966. Charles Brittin. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy J. Paul Getty Trust.

Still other exhibitions focus on art by marginalized groups seeking change: She Accepts the Proposition: Women Gallerists and the Redefinition of Art in Los Angeles, 1967-1978 at the Crossroads School (an exhibition that Catherine Wagley discussed in her last Looking at Los Angeles column); Otis presents Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building; The Japanese American National Museum explores activism in postwar Japanese American Art in Drawing the Line; Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 at the Hammer Museum delves into work influenced in part by the era’s Black Power and civil rights movements; and various exhibitions at the Fowler Museum, the Autry National Center, and LACMA all highlight work by Chicano artists and collectives. One such exhibition that has gathered a great deal of well-deserved attention is LACMA’s Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987, the first-ever comprehensive museum exhibition of the infamous collective of East LA conceptual artists.

While Pacific Standard Time focuses on the LA art scene between the postwar period and the ascent of Reagan, its art-as-activist leanings seem rather timely, as the Occupy Wall Street movement has grown over the past two months. With encampments in New York and other cities attacked and shaken up, the hundreds of tents around LA’s City Hall now represent the largest Occupy encampment in the country. Occupy LA had official support early on, with the LA City Council unanimously passing a resolution to support the movement. “Stay as long as you need, we’re here to support you,” City Council President Eric Garcetti told the occupiers in early October. Mayor Villaraigosa’s gesture of handing out ponchos to protesters on the City Hall lawn offered a stark contrast to the strained attitude of New York Mayor Bloomberg. But after two months, City Hall has changed course, informing its nearly 800 occupiers that they must vacate next week.

Asco, from "The Gores" series, 1974/printed 2011. Photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr. 16 x 20 in Fujigloss Lightjet print. Courtesy Harry Gamboa Jr. Via LACMA.

While walking through LACMA’s Asco exhibition, my friend and I began discussing the allegation–which has been leveled by progressive and conservative critics alike–that the Occupy Wall Street movement lacks clear goals. Though our conversation at first felt tangential, the Asco show proved to be a fitting context for our debate, as the position of the collective can be slippery in its own way. “We weren’t Chicano enough for some, too Mexican for others,” says founding member Harry Gamboa, Jr, in an interview segment included in the show’s extensive catalog. The subversive ambiguity of the collective’s actions, videos, photographs, and interventions produced unease among audiences in the art establishment, as well as among the Chicano community. Hence, the name Asco, which means disgust or nausea in Spanish.

Years before Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills served to question the position of women and film, Asco’s No Movie staged stills from nonexistent films satirizing Hollywood tropes, art house film themes, and the lack of Chicanos’ access to the world of “high culture.” Meanwhile, works such as Pseudoturquoisers, the 1981 fotonovela, features Asco members in what Michelle Habell-Pallan calls “cholo/a drag,” with exaggerated makeup, bandanas, sending up the near-exclusive representation of Latinos as gangbangers throughout popular culture and news media. The piece, shot in 1981, also transcends media issues, seeking also to draw parallels between LA inter-gang violence and the Reagan era Cold War.

Asco. "X’s Party (fotonovela)," 1983/reconstructed 2011. Photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr. 35 mm slides and audiocassette (transferred to digital format). Department of Special Collections, Stanford University. Via LACMA.

It is often noted that in all contexts, whether performing as movie stars, punks, or cholos, the members of Asco always looked glamorous. Through fashion shows, plays, videos, and community interventions, they viscerally became their own medium. Spanning two decades, the collective’s membership grew and shifted, but in every action and artwork, Asco members deployed their own bodies, and did so as impeccably as any mainstream star. Part of Asco’s subversion was to reject the narrative of poverty assigned to their community, and trample out the economic gap to claim beauty, drama, and excess as their own even as they remained financially underprivileged and under-recognized by the art world.

Moreover, Asco was consistently playful. The last room of the exhibition features a videotaped interview from 1983, in which Asco members Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, and Sean Carillo banter playfully about tying the “party line” in knots. Asco’s messages are at once obscure and open-ended, and this obscurity gives the work much of its strength. In the same interview, Gamboa asserts that Asco aims to “instigate people who are taught they have no control… to take an active role in their own life.”