Performa 11: "You don't really love me, you just keep me hanging on"

If moribund is defined as an adjective for that which is approaching death or obsolescence, then perhaps it is the best word to describe my experience of Performa’s last week. This is not to say that the biennial ended without a bang, indeed it seemed that the best was saved for last. However, my patience for big names that delivered less than quality performance did not hold out through the week. My attention veered toward performance that was not lassoed into that calendar of events, but was nonetheless invigorating and contemporary.

Liz Magic Laser’s I feel Your Pain, an intervention-cum-reenactment of political folly, utilized the audience as the stage at the SVA Theater. Actors coming out of their seats performed caricatures of politicians debating, negotiating, or seeking sympathy in the form of romantic comedy.

Scene from Liz Magic Laser's "I Feel Your Pain." Photo credit: Yola Monakhov, via Artfagcity.com.

The performances, projected on a large screen on stage, suggested the spectacle of newsmedia as the whole theater was implicated in the events, making this take on the “living newspaper” a living, breathing beast of the political underbelly. As actors playing Glenn Beck and Sarah Palin sweet-talked one another until converging in a make out session, it felt like the audience was witnessing what everyone was thinking while watching Beck interview Palin on Fox News, but couldn’t say. Many of the parodies felt this way, indulging self-evident posturing while peeling off the veneer of political sincerity or redemption.

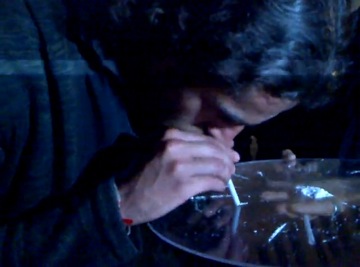

An audience member sampling cocaine offered by a docent in Tania Bruguera's 2009 piece. Image via www.animalnewyork.com

While there was an adrenaline rush of sorts that comes from everyone in the audience realizing that actors could pop up from anywhere, I couldn’t help but sense a formulaic-air on the side of entertainment. I Feel Your Pain was promising on the side of Tania Bruguera’s 2009 staged intervention at the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. At the Universidad Nacional of Bogota, Colombia, Bruguera created a fake panel that included a right-wing paramilitary fighter, a left-wing guerilla, and a refugee displaced by the fighting, as a docent walked through the aisles offering cocaine to the audience.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?&v=x8zy1kULsE0]

Bruguera’s piece was met with a mixture of hostility and humor; some audience members walked out while others noted the ironic situation with curiosity, and even sampled the goods. Causing outrage, debate and some honest dialogue, the piece stirred up the fear and denial about the lack of control Colombian citizens felt about the corruption and deceit they were facing. While Laser’s performance event may have stirred similar emotions, heightened by the exposure of the live feed, it by no means tested boundaries outside of the form of theater, or created new dialogue surrounding our consciousness of manipulation and bamboozlement across party lines.

An emptied Zucotti Park, Nov. 16 2011. Image via www.businessinsider.com.

On the one hand, it’s cathartic to have an outlet through which to laugh about the perversity of our current situation. As Occupy Wall Street was shut down during the same week, it was a relief to go to Laser’s show for free and sit with other people to confront the theatrical lunacy of political showmanship. On the other hand, I wasn’t so comfortable laughing at the actors or at myself in that moment because I felt all too aware of real civil liberties being dashed to smithereens a little further downtown. Facing my own predicament of how to find personal agency at this point in time, I wanted more than a parody.

Participant in Zefrey Throwell's "Ocularpation" on Wall Street, summer 2011. Image via www.artnet.com.

At Art in General, two events, “I’ll Raise You One” by Zefrey Throwell, and robbinschilds‘ “Instruction Construction,” promised very different takes on audience participation. I have to admit, when I read of Zefrey Throwell’s Ocularpation performance on Wall Street this past summer, I didn’t see it as much more than a pseudo-political, superficially misguided street performance. The kind where passers-by could gawk at the nudity, say, “how kooky!” and walk away. That was apparently enough, however, for Throwell to be curated into Performa.

Zefrey Throwell's "I'll Raise You One" for Performa at Art In General. Image via www.artingeneral.org.

“I’ll Raise You One,” a week-long strip-poker game held in the storefront of the gallery was pretty much just that. While attracting a huge crowd around the windows, and many volunteers desiring to take part in the performance, there wasn’t much more to it than the game itself–and oh, yeah, people getting naked. I was puzzled by the idea that the radical nature of the performance came from its context of public nudity. With pretexts for nudity in performance art going back some 40 odd years, this was less than revelatory. Was Throwell’s piece meant as a comment on our current economic climate? On the economics of the art world? Who’s to say? It won’t be Throwell, nor will it be me.

Sonya Robbins performing "Instruction Construction" for Performa at Art In General. Image via www.artingeneral.org.

In the gallery, robbinschilds presented a minimal, site-specific installation for Performa. Viewers-turned-participants were invited to perform actions responding to the space of the gallery via headphones. Part dancing and part physical exploration, references to John Baldessari’s “I am making art” and Dan Graham’s “Performer/Audience/Mirror” intersected in this piece, which became a reflection on presence and place. Working off of the idea of feedback, the instructions given on the headphones, the body activating the instructions, and how that activity came to bear on the space, formed a loop where participants were as much engaged in their own physical responses as to their focused attention on the gallery’s architecture. I will further trace this conceptual framework through performances seen in the same week, but I must first bid adieu to Performa with a few words on the piece I actually regret not seeing.

Ragnar Kjartansson and fellow performers in "Bliss," commissioned for Performa at Abrons Art Center. Image via www.nytimes.com.

Ragnar Kjartansson’s Bliss, a twelve-hour restaging of the final, three minute aria in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, won the Malcolm McLaren Award for best performance by a Performa artist under forty. With rave reviews by Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz, it is clear that the Icelandic artist nailed the recipe for appropriation and endurance to the satisfaction of the audience. Described by Jerry Saltz as possessing “the transforming hallucinatory power of the rococo and the amazing sight of an artist earnestly, even desperately trying to cut through 21st-century irony,” Kjartansson, joined by nine singers in period costume, sang the aria for twelve straight hours, without bathroom breaks and over the course of eating and, of course, drinking. No one fainted, no one was hospitalized, and as Saltz explains:

For me, Ragnar is an anti-Marina (Abramovic, that is). Instead of seeing narcissism, egomania, and glamorous existential suffering, I glean something Icelandic — a way of courting chaos with fortitude, a sense of the absurd and acceptance. There were no histrionics, no audience members trying to take over the proceedings, or melodrama. I imagined what American performers might do in these straits, shedding garments, removing wigs, vacating the stage to rest. Instead these Icelanders moved into entropy by drinking more, accepting some abject doomed state they and we are all in. Maybe it comes from living in the dark for four months every winter.

Curious about the stages of decay and entropy that surely evolved over the course of this performance, I can only guess at the feelings of solidarity the audience may have had with the performers as the aria-loop edged on its 8th hour. Labor, exhaustion, and the determination to trudge on make Bliss sound as if it were a fascinating, dead-pan suspension of “the end,” a kind of emotional crack leading to a state to which the title corresponds.

Rehearsal image of Chase Granoff by Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Via https://paulsepuya.com

Where was I? I am pretty sure that I was actually in Long Island City, Queens. And happy there I was, watching Chase Granoff’s intuition is preceding over my understanding at The Chocolate Factory Theater. Standing behind a table, Granoff served local wine and bread, handing out a small letter-pressed poem by writer (and Art21 Blog columnist) Thom Donovan. Taking off his glasses and shoes, Granoff then proceeded to execute an improvised dance across the floor, with subtle shifts in light and shadow designed by Megan Byrne. There was nothing grandiose here, nor was there any mystery. It was clear when Granoff was searching for the next movement, which was conveyed by a quality of receptive stillness that kept the audience equally receptive.

Chase Granoff improvising " intuition is preceding over my understanding" with light sculptures designed by Megan Byrne at The Chocolate Factory Theater. Image credit: Steven Schreiber. Via www.nytimes.com.

It wasn’t a dance improvisation so much as a phenomenological investigation of the process of improvising movement. At one point, in a pause during the classic Bill Dixon trumpet improvisation, Granoff let out a sharp sigh and hum, which rippled through the audience. Everyone was lending their concentration to the piece, as witnesses to the phenomenon of intuition. The dance was not a display of virtuosity or heroism, but it was a discursive space. I have appreciated this in past performances by Granoff, who advocated for dance’s visibility on the Performa roster in 2007.

Ryan Kelly and Yve Laris Cohen performing "Reusable Parts/Endless Love" at Danspace Project. Image via www.gerardandkelly.com.

Picking up the conceptual threads of robbinschilds at Art in General and Granoff’s discursive dance-making is Gerard and Kelly’s Resuable Parts/ Endless Love (RP/EL) at Danspace Project. Deconstructing Tino Sehgal’s Kiss, which was performed at the Guggenheim in 2010, the choreographic duo re-staged the piece with moving walls and four trans-queer performers. A performance installation that wound toward intimacy for over one hour, RP/EL managed to illustrate the cold isolation of a trans-queer body folding in on itself in an attempt to reenact both lovers in the Kiss, and unfolding into a bold confrontation with another body wrestling in the sway of seductive power. I was changed by this meticulous, raw and exposing performance. Look out for a future post on this piece in an upcoming edition of this column.

Burr Johnson and Erin Cornell perform John Jasperse's "Canyon" at the BAM Next Wave Festival. Image credit: Julieta Cervantes. Via www.metro.us.

This post would not be complete without mentioning another performance I caught away from the throws of Performa, at BAM’s Harvey Theater. John Jasperse, who set the bar for dance as contemporary art over a decade ago and continues to thrive, premiered Canyon as part of the Next Wave Festival. The driving force of the piece–to convey the feeling of losing oneself in an experience–was propelled in great ways by the swelling drones of Hahn Rowe’s prepared guitar, strings and percussion quartet. I wanted to strip away the frenetic, neon-tape-as-visual-design and box on wheels amidst the dancers, yet I did find a sweeping quality to the movement that teetered between the throes of ecstasy and falling away, or “dropping out.” The dancers, at times repeating phrases in the search for solitary wonder, other times listlessly lying in pairs, reveal the emptiness of that search, where wonderment evades the senses and we become paralyzed by the unknown. Canyon points to something out there, way beyond the faculties of the body, and beyond the bounds of intimacy, as the dancers spiral in exhaustive turns into a great, wide open.

Dancers performing "Canyon," Production shot. Photo: Tony Orrico, https://artforum.com/