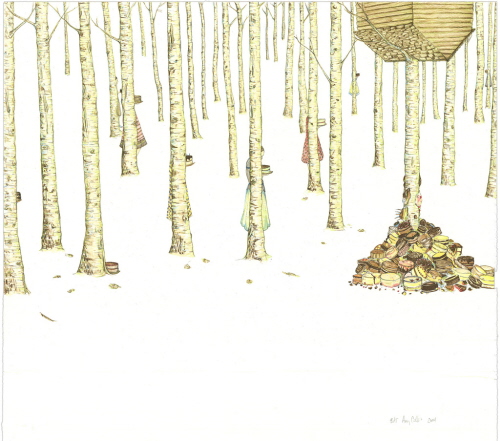

Amy Cutler. “Cake Toss,” 2004. Lithograph in colors on Fabriano Artistico Hot Press natural white, 21-1/2 x 24 inches (image and sheet). Edition: 39; publisher: Universal Limited Art Editions, Bay Shore, NY. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

Fantastical narrative is a guiding principle for many artists who have come to prominence in the past decade; Amy Cutler and Dana Schutz are foremost among these. Both possess extraordinary imaginative powers, creating worlds that are entirely fresh and singular. This month’s and the subsequent post of Ink will focus on the prints of these two young artists, respectively, both of whom have created a significant number of prints that directly relate to their paintings and drawings.

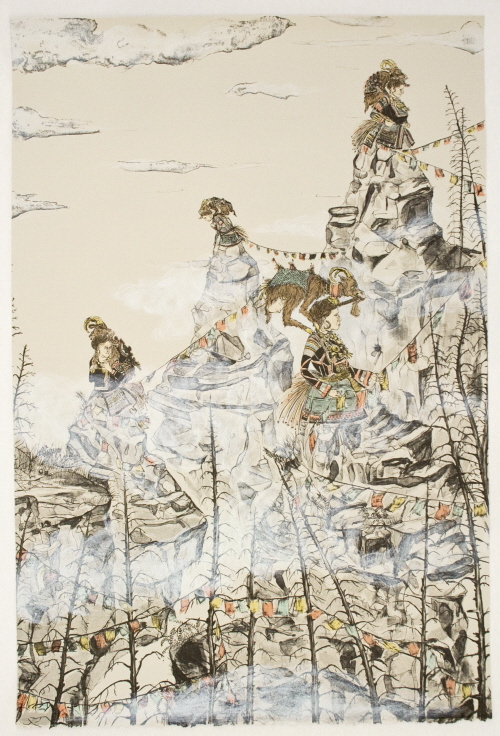

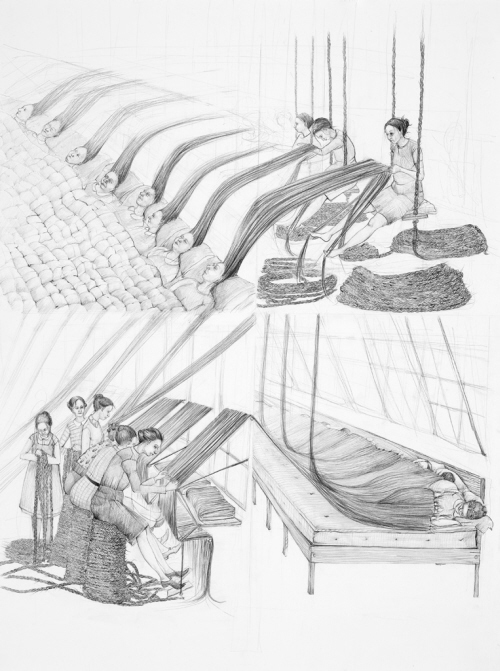

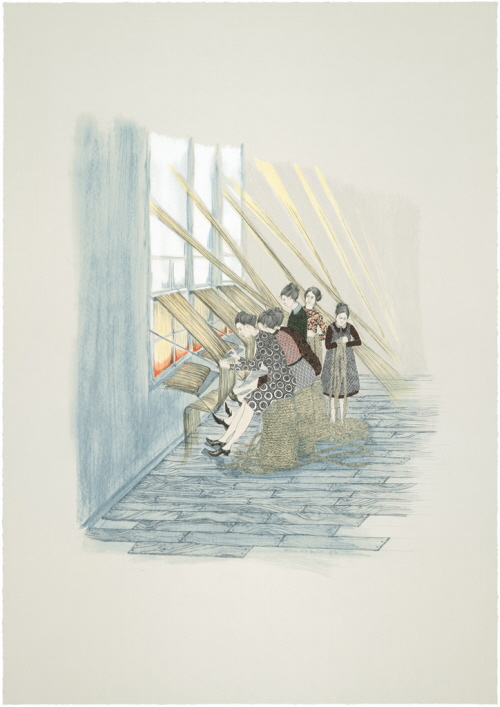

Amy Cutler’s world is populated by plain women who hail from an imaginary or bygone era. They wear vaguely traditional dress of the artist’s invention, informed by an amalgam of periods and cultures, and engage in surreal or unlikely tasks, often with serious or sober expressions. Like many contemporary artists (i.e., Enrique Chagoya, Kara Walker, Laylah Ali, Shahzia Sikander), Cutler has reached beyond the history of Modern art for inspiration, finding a new vocabulary in which to address the contemporary condition. The artist has cited Persian miniatures, fifteenth-century German painting, Japanese ukiyo-e, and medieval art as influences in her work, as well as the folkloric heritage of the Brothers Grimm (see Lisa Freiman, “The Marvelous World of Amy Cutler,” in Amy Cutler [Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2006],10). These precedents are certainly apparent in Cutler’s jewel-like compositions that are lavished with minute detail. Her technique is alluringly skilled, but this is by no means the focus (when her process is mentioned, it is usually to note the meticulous manner in which she applies patterning to textiles). Instead, any such description is primarily an enriching factor in the artist’s bizarre narratives that instantly capture the imagination.

Though Cutler’s work has sometimes been dismissed as illustrative (a tendency abhorred by an older generation of critics and artists), this is the very quality that contributes to its beguiling power. Cutler’s attention to detail grounds the work in specificity; the objects and environments they depict are recognizable and appealing. These familiar elements rope the viewer into a process of telling a story to “make sense” of it. This impulse is noted by Freiman and analyzed in further depth by curator Laura Steward in her introduction to the catalogue for Cutler’s recent exhibition at SITE Santa Fe: “your impulse is to imagine a narrative that could take place in the scene she depicts, and further, to imagine what that narrative might mean” (Amy Cutler: Turtle Fur [Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011],12). Yet there is no such meaning to be found; interpretation is intentionally left open-ended.

Cutler thus deftly awakens the viewer’s compulsion to apply “morals” to her tales. One common response is a feminist one – the industriously toiling women of Cutler’s world are often engaged in “women’s work” of an absurd nature, prompting empathy or outrage for their perceived thankless labor. Yet Cutler’s intention is contrary to this understanding. Addressing her proclivity for female subjects in an interview with Aimee Bender, she states “I love the idea of a fictional utopia of women who are strong and self-reliant” (ibid., 23). She also notes that her experience of attending an all-girls school may have influenced this preference. Likewise, she does not espouse the idea that her women are engaged in drudgery. When questioned on this point, she explains, “I think it comes from my fascination with anything that is meticulously crafted – things that are created by individuals with specifically honed skills…I am especially drawn to methodical work that requires a lot of concentration…[T]he rhythm and repetition…lends itself to introspection” (ibid., 22-3).

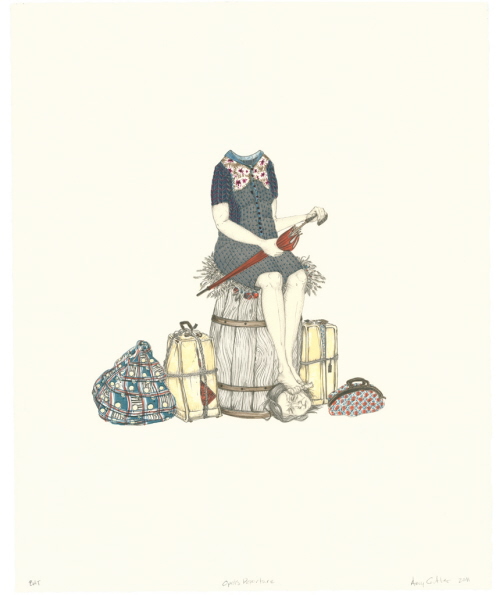

Amy Cutler. “Widow's Peak,” 2011. Lithograph in ten colors, 36¼ x 24½ inches (image and sheet). Edition: 25; publisher: Tamarind Institute, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; collaborating printer: Bill Lagattuta. Courtesy Tamarind Institute.

Though grounded in story-telling traditions, Cutler’s dream-like images (which are often tinged with the macabre, like folk tales) are entirely contemporary in their exploration of the illogical and contradictory. In 2005, Cutler shared her interest in the subconscious and associative processes of the mind with Freiman: “[d]aydreams and things that I so often do not hear correctly constantly enter my work. If something sounds strange, I turn it into a mental picture and that is very entertaining” (Amy Cutler [2006], 20). The artist also makes a concerted effort to depict her dreams in a journal, and sometimes these become elements in her finished work. Though Cutler does not cite Surrealism as a direct influence, Freiman notes in her essay that these practices were also embraced by its leader André Breton, “so that the artist’s imagination could roam freely, unencumbered by the obligation to create realistic representations of life” (ibid., 21). Indeed, Cutler’s women are often doing something impossible that could only exist in the realm of painting, drawing, and prints, where the laws of physics and other parameters of the “real” world can be stretched.

Likewise, Cutler departs from the narrative graphic traditions of the past in her spare description of setting. Her figures often float in blank field of open paper, or with minimal description of surroundings. She explains, “I trust that the viewer is able to follow and understand the spatial relationships within the painting without every detail having been laid out. I see the absence of a literally described place as an entry point in the painting…the viewer becomes an active participant in the creation of this world” (as quoted in Bender, Amy Cutler: Turtle Fur, 22). As discussed by Steward, this engagement from the viewer is intrinsic to Cutler’s art. Using Susan Sontag’s ground-breaking 1966 essay “Against Interpretation” as a counterpoint, Steward argues that Cutler’s work (and those of her like-minded contemporaries) actively encourages interpretive looking – even depends upon it – in a way that Sontag never could have imagined. In a break from the abstract, and arguably “content-less” art of the Postwar period (which was Sontag’s subject), today’s narrative art resists the technique- and biographically-based discussion that defined Modern criticism, intensely engaging the viewer in quixotic worlds that curtail any such analysis.

Amy Cutler. "Tiger Mending," 2003. Etching and aquatint in sepia with chine collé, 9 7/8 x 9 7/8 inches (image), 19-1/2 x 16-3/4 inches (sheet). Publisher: Lower East Side Printshop, New York. Courtesy Lower East Side Printshop, New York.

As Cutler has made clear in interviews and artist’s talks (see her recent talk at Site Santa Fe – also excerpted here), her subjects are frequently born of personal experience or news events. For example, Tiger Mending, 2003, one of Cutler’s first prints (completed as a resident at the Lower East Side Printshop), was influenced by the beginning of the war in Iraq. She was looking at a book of Mughal paintings and listening to news of the war on NPR, when she settled on a miniature titled Akbar Slays a Tigress that Attacked the Royal Entourage (coll. Victoria & Albert Museum, London). Though originally intended to glorify the event, Cutler saw it as “a battle over territory. It made me think of the aftermath and the casualties of war…this is where I applied my utopian bandage” (ibid., 24). In the resulting etching, Cutler imagines four women in an open field who busily work to repair the damage that has been done to the tigers in the Mughal painting, carefully stitching their corpses; on the far horizon are minute figures of four warriors on horseback.

Amy Cutler. “Hair Mill,” 2007. Graphite on paper, 29-3/4 x 22-1/4 inches. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

Amy Cutler. “Weavers,” 2008. Lithograph in colors on Rives BFK gray, 34-1/8 x 24-1/8 inches (sheet). Edition: 34; publisher: Universal Limited Art Editions, Bay Shore, NY. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

Cutler’s recent show at Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects (closed November 5) explored the artist’s prints to date, including a number of related drawings, working proofs, and intaglio plates. It is rare and welcome to see a Chelsea gallery dedicate an exhibition to an artist’s prints, and even more refreshing that pains were taken to provide contextual and working materials. Two sculptural objects with related works have been criticized as off-topic; but they did not distract from the rich dialogue between the prints and the paintings and drawings on view. For example, the graphite drawing Hair Mill, 2007, became the source of a 2008 series of lithographs Cutler created at Universal Limited Art Editions (Groomers, Provisions, Reserves, Weavers) in which she separated its elements into four discrete compositions. Working proofs further illuminated the artist’s decisions as she worked on the series, showing experimentation with color and background details.

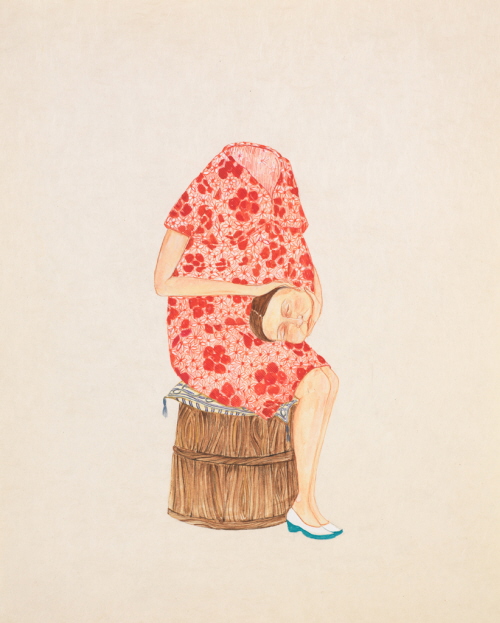

Amy Cutler. “June,” 2010. Gouache on paper, 13 x 10-1/2 inches. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

Amy Cutler. “Opal's Departure,” 2011. Lithograph in colors on Fabriano Artistico Hot Press white, 15-1/4 x 12-1/4 inches (sheet). Edition: 50; publisher: Universal Limited Art Editions, Bay Shore, NY. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

June, 2010, a gouache on paper, and Opal’s Departure, 2011, a lithograph in colors, demonstrated an entirely different relationship between the two media. Both show a seated woman whose head is detached from her body. Though not on view at Tonkonow, another 2010 gouache that was included in the SITE Santa Fe exhibition, April (ibid., 82), provides further insight to the artist’s development of the theme. Both of the 2010 gouaches depict a woman seated on a simple implement (a metal bucket or wooden barrel) with a pillow for a cushion; June holds her head in her lap while April perches her feet atop it, as in the 2011 lithograph. The addition of suitcases and an umbrella in Opal’s Departure takes the idea a step further with a tongue-in-cheek title that suggests dual readings; has Opal literally lost her head, or is she going somewhere, or both?

Inevitably, any discussion of Cutler’s work provokes a barrage of questions in the viewer’s mind, with no resulting sense of closure or satisfaction; neither do they provide any moral compass or lesson. As noted by Freiman, this ambiguity is distinctly adult and rooted in the complexities of modern life (Amy Cutler [2006], 16). Rather than providing a pat explanation of the world or even a clever puzzle to be “solved,” Cutler’s women unleash the viewer’s imagination, open possibilities for new avenues of thought, and promote an alternative understanding of the world.

Amy Cutler’s work will be featured in the following upcoming exhibitions:

- Huntington Museum of Art, Huntington, West Virginia, March 17 – May 13, 2012

- University Art Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, July – September 2012

- “Drawing Stories: Narration in Contemporary Graphic Arts,” Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, May 19 – July 15, 2012

Pingback: Brown Paper Bag » Amy Cutler

Pingback: Spring critique 2014 | works and progress

Pingback: Spring critique 2014 | Colleen Wampole