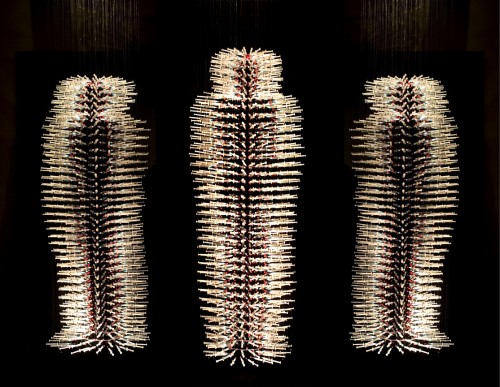

Daniel Joshua Goldstein. "Invisible Man X 3," 2010. Photographic triptych of original sculpture: syringes, red crystal beads, steel wire, electric motor. Each photograph in triptych: 65" x 32". Collection of the artist.

“Sickness shows us what we are.” ~ Latin proverb

“You see, somewhere our unconscious becomes material, because the body is the living unit, and our conscious and unconscious are embedded in it; they contact the body. Somewhere there is a place where the two ends meet… and that is the place where one cannot say whether it is matter or what one calls ‘psyche’.” ~ Carl Jung

Illness and art have a long, entangled history. The human need to ameliorate suffering, to engage in a creative practice that mitigates the sense of loss brought on by illness or in some way counteracts the illness itself (however illness is imagined) is universal. A persistent example is the making of effigies–sometimes to focus the attention of the sick on images of the supernatural world (for example the Isenheim altarpiece) or to attempt to bring about change in the body itself through a mimetic process of healing (such as votive objects in the shape of body parts).

In the contemporary world, HIV/AIDS has been a potent catalyst for the making of art which marshals social activism, engenders a supportive community, or challenges the public to reinterpret the meaning of the disease. In this way, art about HIV/AIDS is a gauge of social conscience and cultural consciousness.

Daniel Joshua Goldstein. "Icarian Angel," 1993. Photograph of the original found object sculpture: leather, sweat, black felt in case of wood, copper, Plexiglas. 36.125 x 30 x 6 inches. Private collection.

San Francisco activist and artist Daniel Joshua Goldstein has been living with HIV since 1984. As one of the few HIV+ survivors from the early time of the epidemic in America, he is an historic witness to the thirty year transformation of society’s response(s) to AIDS. Goldstein is one of the five subjects interviewed in David Weissman’s documentary film We Were Here, which records eye-witness accounts of the devastation and collective trauma wrought by the onslaught of the illness.

The human effigy has played a significant role in a number of Goldstein’s AIDS-related works, beginning in 1993 when he first exhibited the “Icarian Series” in New York City. These were the salvaged leather skins of exercise machines from a gay gym, their golden surfaces broken down by a decade and a half of physical impress, friction and sweat. As remnants of an entire culture, lost overnight as it were, the eerie figures shining from the surfaces could not but denote all manner of connections to the sacred, the saintly and the spooky. The force of these effulgent effigies was so strong that during an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1998, curator Rosemary Crumlin told Goldstein she would often find visitors openly weeping in front of them.

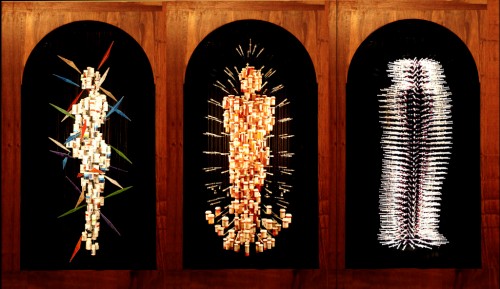

Daniel Joshua Goldstein, "Triptych: Medicine Mother, Medicine Man, Invisible Man," 2011. Photographs of Goldstein's mixed media sculpture on Duratrans, light box, wood. Courtesy of curator Carol Brown, Durban, South Africa.

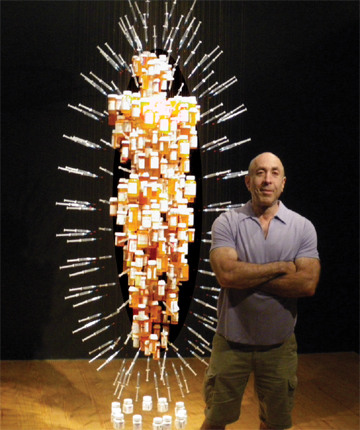

The first in a series of suspended figures made of medication paraphernalia, “Medicine Man” was created for the Fowler Museum’s 2008 internationally-focused Make Art/ Stop AIDS exhibit. Goldstein became involved in this and the larger umbrella project of the same name through his close friend, the scholar, critic and curator David Gere of UCLA.

A current exhibit, “The A.R.T. Show” at the Tatham Art Gallery in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, features several iterations of Goldstein’s medicine figures including a lightbox with life-size photographs of three of his suspended effigies. The Tatham exhibit also features a “cabinet of curiosities” in which one of the original leather Icarian pieces is featured.

"Cabinet of Curiosities," 2011: a wood and glass folding case by Xavier Clarisse containing artworks by various artists, including Goldstein's leather relic of the early AIDS crisis in San Francisco, "Icarian Angel." The Cabinet is part of the exhibition "The A.R.T. Show," currently at the Tatham Art Gallery in Pietermaritzburg, curated by Carol Brown. The exhibit will tour several museums in South Africa in 2012.

“That original, haunting human form that appeared so many years ago on the leather pieces has continued to act as a prototype in all of my AIDS-related projects,” says Goldstein. “In the beginning of my career I was not an artist who focused on the human form, but now it has become one of the most significant facets of my creative output.”

In 2009 Goldstein worked with the craftspeople of the Umcebo Trust in Durban to make “Medicine Man for South Africa.” Umcebo’s members fashioned dozens of elegant bead spindles that formed a cloud around a figure composed of the medication bottles donated by HIV+ locals. The colors of the spindles corresponded to side-effects brought on by anti-retroviral drugs prevalent in South Africa–many of which are incredibly toxic and no longer used in the United States. Below the figure, visitors were encouraged to write down their own experiences of HIV drug induced side-effects. Each day the paper disk recording these stories was replaced. The round leaves were later gathered into a collective journal.

Daniel Joshua Goldstein. "Medicine Man for South Africa," 2009. Medicine bottles, hand-beaded glass and wire spindles, steel wire, paper disks, crayon. Life-sized. Collection Durban Art Gallery, Durban, South Africa.

The most well known of Goldstein’s medicine bodies is probably “Invisible Man,” which has been exhibited in a number of venues in Vienna, Miami, New York City and San Francisco over the past two years. Composed of 864 syringes, each tipped with a red crystal bead, the body that the viewer first perceives proves to be an illusion. The figure in the center is an optical effect produced by the hollow space around which needles converge. This is the most concise example of “the presence of absence,” the evocative phrase that Goldstein often uses to describe his AIDS-related works.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=He9hhunEHns]

In December 2011, as a part of its World AIDS Day program, Grace Cathedral in San Francisco exhibited Goldstein’s “Invisible Man” in the center archway of its entrance. The piece became a temporary companion to another artwork featuring a radiant figure and exhibited nearby in Grace’s AIDS Interfaith Chapel: Keith Haring’s “Life of Christ.” Covered in white gold-leaf, it gives off a powerful radiance.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zdTLqJv3p0w]

As a viewer moving back and forth between the pale glimmer of Haring’s image and the chandelier-like shimmer of Goldstein’s, I was reminded of what art historian Barbara Maria Stafford had written about luminous bodies created for audiences during the horrors of the French Revolution. In this period of massive social trauma and violent cultural upheaval when thousands died, people would gather to watch ghostly figures projected from a magic lantern or fantoscope onto black curtains, the walls of crypts, even billowing clouds of smoke. “[These] rapturous conjurations commemorated the…ghostly reappearance of individuals torn from the natural world. Their miraculous, if fleeting, machinic resurrection as cloudy or crystalline lightforms could not be interpreted as just entertainment…the fantoscope performed the work of memory, making the absent present.” (Stafford, Echo Objects, 129).

Daniel Joshua Goldstein in front of his suspended sculpture "Medicine Man II" at the Station Museum in Houston, TX, 2010.

Even as effigies of the body seek to mime the experience of the living form, they offer the human consciousness a way into a greater experience–that of being more than a body. The effigy that gives off light visually expresses this paradox. An image of the radiant body such as Goldstein’s “Invisible Man” is a manifestation of a mystery, a tool for possible healing, a way to close a rupture through rapture.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?