Paul Ha is the new director of the List Visual Arts Center, Massachusetts Institute for Technology’s (MIT) contemporary art museum, which focuses on experimental exhibitions and a wide range of educational programs and publications. Earlier this fall, Ha talked to MIT news about his prospective position and vision for the List:

“What excites me about the List is the arts at MIT are rooted in experimentation, and the List excels at that mandate. My goal is to try to build on the List’s strong reputation while also expanding its role in the lives of students and the greater MIT community. Just as the MIT Museum explores the foundations and frontiers of science and technology, the List Visual Arts Center explores the foundations and frontiers of the visual arts, serving as a laboratory for forward thinking and experimentation in the art world.”

Previously, Ha served as the inaugural director of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM). He began by overseeing the construction and opening of a new facility designed by Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture. At the end of his tenure this past November, Ha joined the List Visual Arts Center having produced 92 exhibitions at CAM and having brought more than 220 artists to St. Louis. He offered artists such as Laylah Ali, Un-Fei Ji, David Noonan, Alexander Ross, Aïda Ruilova, and Gedi Sibony their first museum exhibitions; raised more than $40 million for the institution; and established a $5 million endowment–the Museum’s first.

Ha has also served as the deputy director of program and external affairs at the Yale University Art Gallery. Most importantly, Ha was the Executive Director (1996-2001) and Associate Director (1993-1996) at White Columns in New York – a position that was the catalyst of his early career endeavors. We began our talk by discussing this point in his career, because I recognized something familiar in the timbre of his voice while watching a 1999 video by Marc Ostrick that made me think, “I wish I had met Paul Ha then.”

Ha has lectured widely on contemporary art, the emerging art scene, and the importance of not-for-profits. Also, Ha has served extensively on panels and has been a visiting critic, lecturer and consultant at many institutions, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the Federal Advisory Committee on International Exhibitions, Pew Fellowships in the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, and at numerous colleges and universities.

It’s an absolute pleasure to mark this end-of-the-year post with Paul Ha’s new beginning at the List. On this occasion, I would like to congratulate him and wish him the very best on behalf of Art21 and this column’s readers.

Georgia Kotretsos: I would like to open our conversation with a video by Marc Ostrick, shot in 1999 at White Columns, New York, during a time when you were making around 900 studio visits per year.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEJmP2XnkAU]

Your drive, energy and commitment clearly reflects a different era, and makes me wonder whether your “kind” is at risk of extinction. In 2006, you told Jeannette Batz Cooperman that “contemporary art is something that is always being created. If you stop looking now, it’s already old news.” What is the role, responsibility and expectations of the visitor?

Paul Ha: Thanks for your comment, Georgia. I’ll bet there is someone out there right now who is young and who is driven to see as much as they can and to be as current as possible regarding the contemporary art-making scene – just as I was twenty years ago. I can also say that in 2011, I no longer am making 900 studio visits a year and my interest and curiosity has broadened to include artists other than just those who are emerging [1].

The role of the visitor to me is simple – their job is to “look” at the artwork. [2] I think many times, visitors are distracted by some of the other reasons that we visit museums: to be social, we go out of a sense of obligation, to shop, or we end up there by mistake – but even I find that some of the times that I visit museums, I do not get a chance to do an object study lesson or look at an object closely enough – to really, really look at it, and then to think about it [3]. But to put my quote for Jeannette Batz Cooperman in context, the answer was specifically targeted towards my work at White Columns – and my function there was to discover artists that are young and who were then considered emerging.

GK: In the case of Sean Landers and Aïda Ruilova, you’ve been able to follow their careers since your first visit to their studios more than 20 years ago. What is that long-term investment like?

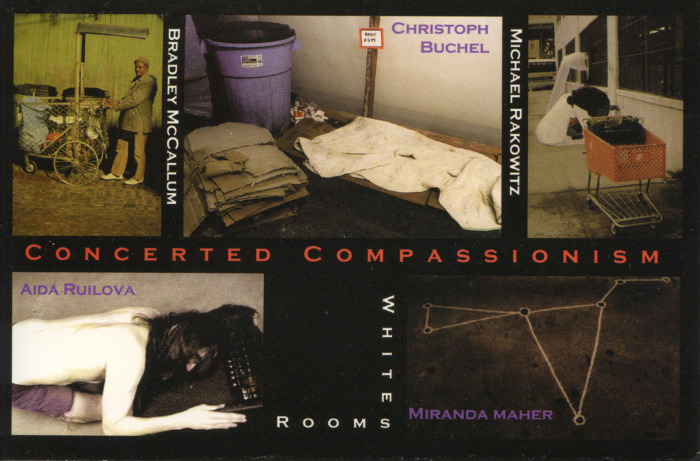

Invitation for "Concerted Compassionism;" "White Room: Aïda Ruilova;" and "White Room: Miranda Maher;" at White Columns, September 2000. Courtesy White Columns.

PH: It has been a privilege to be able to follow some of the artists and their work for such a long time. Additionally, what has been interesting for me is that there are many many more artists whose work astonished me then, more than 20 years ago, who are no longer making art. The survival rate to being an artist and to remain one is slim – I can attest that there is a huge attrition rate in becoming an artist. That’s why I respect so much those who stick with it – and those that survive. When I first saw Sean’s work he was just out of Yale–he was an emerging artist–and he and a bunch of others moved to New York City [4]. I happened to arrive in NYC about the same time–around 1986–so all of us were, in a way, starting a new adventure, all with different hopes. [5] When I made my first studio visit with Sean in 1986, it wasn’t the Sean Landers we know today, and I wasn’t a museum director. The visit was between an artist fresh out of school asking a new friend he’d made, who was a preparator at a gallery, and Sean just wanted someone to see his new work, and to talk about it. It is interesting for me that the “me” today asking an artist for a studio visit is completely different from the “me” then, asking an artist for a studio visit.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGcBRiFWYtY]

If you look at the work that Sean is doing now and you look at the work he was doing in 1986, you may say it is by two different artists, unless you’ve seen all the different directions and the chances the artist took with the work. What also has been interesting is that when an artist does make a change to their work, they are often unsure, insecure about it and undecided as to what they’ve just done. And it is during this moment that they often ask someone to come over for a studio visit, usually a friend or another artist. I think it takes a certain kind of artist, which is to say someone who is incredibly courageous, to be willing to make changes to a body of work that they are so well-known for. It takes courage to be an artist, in addition to talent.

GK: An artist friend recently told me, “I’m not keen on studio visits, it’s as if someone is walking around inside my head.” Is the studio space always about a physical space?

PH: In the end, the studio visit is for that artist. And what is so special about a studio visit are the conversations–while the artist and you are simultaneously looking at an object. Art conversations happen all the time, at parties, in restaurants, in a classroom setting; however, in a studio visit, the focus is for that particular artist. Your friend is right; the visitor IS walking inside the artist’s head. But it is at the invitation of that artist.

GK: Does the studio visit in your opinion rank as high as it used to in the hierarchy of a curator’s things-to-do list today, or could the art fair be considered to be an alternative quick fix for the busy ones in transit?

PH: Going to an art fair is like going to a record store, versus going to an artist’s studio is analogous to being invited to a recording studio while a musician is making a new album. There is a world of difference. A studio visit is a privilege, an artist is bringing you into their delicate and private world and we get to be part of that, even just for a night. Again, the studio visit is all about the conversations while both the artist and the visitor are simultaneously looking at an object. The real focus of the studio visit is the artist and their work–whereas the focus of the art fair is experiencing the art market at work.

Art fairs are great for many things, especially as a way to see broadly what the dealers feel is in demand. But I don’t know any curator that would seriously consider using the art fair to work on an exhibition or to do their research. There is such value in a long term relationship that gets developed during the visits and the conversations that leads to better understanding of the work–those are invaluable, and you simply do not get that from an art fair. At art fairs, it is mostly the dealers who bring valuable knowledge to the work, but I feel in contemporary art that the curators would not be doing their job if they didn’t make a direct connection with the artists they are thinking about. In a way, a curator’s role is to be the voice of the artist–to point out or to communicate something that the artist is unable to. And at art fairs, the voice is that of the dealer and collectors; rarely do artists have a voice.

GK: In recent articles, you often used the word “laboratory” in regards to the MIT List Visual Arts – a word that artists respond to with enthusiasm. It implies experimentation, potential, and a space where artists can take liberties. So, what kind of a lab do you envision?

PH: MIT is an amazing place that encourages entrepreneurism and has a culture where putting forth the best idea is highly valued. And for obvious reasons, they are known for their exceptional engineering and science departments. But what the general public may not know is that the Institute also excels at humanities and business. Our Sloan School of Management is ranked as one of the best business schools in the world [6] and our schools in architecture, linguistics, political science, literature, visual arts, and performing arts, to name a few, are also exceptional. And as the contemporary art museum at MIT, one can easily misconceive that our mandate is to have an exhibition program that features technology. And because artists have always embraced the latest technology [7] and love incorporating them into their work, one can easily make that assumption. But if we were to think in terms of music, to be cutting-edge and avant-garde in music does not necessarily mean using computers or the other newest “tools” for their craft. What makes a piece cutting-edge and avant-garde is the newness of the idea. The latest technology simply is an instrument that the musician may or may not use. One can use a 300-year-old violin to create something that is unconditionally avant-garde.

When you mention the word “lab” and you associate it with MIT, one immediately thinks of test tubes or cyclotrons. But for us, a lab means, as you put it, experimentation, potential, and a place where liberties can be taken by artists. And these beliefs are all in complete alignment with MIT and its culture – finding ways to put forth the best idea to present something new. To have a lab means that there’s experimentation going on, there’s vigorous dialogue going on, there’s failed attempts that we learn from. A big part of being a lab is about discussions and collaborative thinking. That’s what we hope to have at the MIT List.

GK: This question will be all about money and art, something you understand, raise, and use wisely. You said once that “Money will always come. Money follows passion.” And later in 2008, you added “The best thing a contemporary art museum can do for is local artists is to show them and give them money. […] Our goal is to get to where an artist can actually leave their job for a year.” Your last statement refers to the Great Rivers Biennial, an initiative that has had an enormous impact on contemporary artists in St. Louis. But let me ask you this, all the way from Athens: what happens when there is little or no money for contemporary art? What could happen to art and what could happen to its artists?

PH: I feel for everyone in Greece and the financial turmoil that you all are facing. It is serious to be sure. When you are not worrying about how to survive, and there are plenty of resources, it certainly is a lot easier to succeed. But there is solid evidence and proof from the art world that artists and the art world are adept at creating something significant when they have almost nothing. That it may be exactly because of the poor conditions that significant movements in the arts resulted. For example, in the early 1970’s, with artists moving to the SoHo district in NYC and with no real support system for emerging artists, places like White Columns, Artists Space, and Franklin Furnace opened their doors [8] – and have remained open and serving artists for close to 40 years. Out of necessity they created something for themselves, and those institutions became part of a lasting dialogue. In the late 1980’s, young British artists led by Damien Hirst started renting warehouses to exhibit their work, and they later became known as the YBA’s (Young British Artists) [9]. All these examples came out of need. Through their actions, they made something out of nothing and in the end, they may have even leapfrogged conventional methods and created new systems. I think it was Holland Cotter in the New York Times who said–and I’m paraphrasing this–“the best art is made when there’s no money to be made.”

GK: What has your musical intake been at different stages of your career? On the occasion of this question, which song would you say best communicates Paul Ha as seen in the opening video, and which one conveys Paul Ha right now?

PH: That video was really fun to see. My son Peter, who is in the video, was then just born, so that video is now 13 years old! That was when I was ending my work at White Columns where I was able to work with an exceptional crew consisting of Lauren Ross and Teneille Haggard. I would say the soundtrack during those days would be DJ Shadow’s Midnight in a Perfect World. We would often host evening events, and on many nights I would get home way past midnight. While walking on Bleeker Street, that song would often play in my head. But if you see me at the Logan or the Lambert airport today, more than likely, I’ll be listening to Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes. Simply the most beautiful sounds I’ve heard.

And, that’s a wrap!

[1] At the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, I curated and exhibited the works of Sean Landers, after following his work for over 25 years. And along with Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson, Director and Chief Curator of the Aspen Art Museum, we co-curated Aïda Ruilova: Singles 1999-Now, a survey of her single-channel work spanning from 1999-2007. At that point they were no longer considered “emerging artists,” although when some of the work was made, they certainly fit into that category.

[2] Now there are many types of “visitors;” I am mostly speaking of the general public. If it’s a curator of art that visits a museum, or a collector who loaned a piece to that museum, or an artist, their reasons for looking at the show will be entirely different.

[3] Dr. Abhilash Desai, a professor of psychiatry, is quoted saying, “We spend more time interpreting our experience than in experiencing.”

[4] A big crop of Yale MFA graduates moved to New York City around 1986, including John Currin, Byron Kim, Maya Lin, Richard Phillips, Jack Risely, and Lisa Yuskavage. Many of them shared studios and also created a “support” base for each other–helping each other to get exhibitions and into galleries.

[5] Most of the friends that I made around the time of 1986 were artists. They wanted to be famous artists. I wanted to end up in a museum. We spent many nights strategizing and talking about how we were going to do this.

[6] In a 2011 U.S. News & World Report, MIT’s Sloan School of Management was ranked as one of the top 3 business schools in the world.

[7] Remember “web art,” “fax art,” and “cyber art?” Art, in my opinion, will always remain something that has to do with ideas as opposed to mediums.

[8] White Columns was founded in 1970 by Gordon Matta-Clark and Jeffrey Lew. Originally founded as 112 Greene Street (where it was located) it morphed into 112 Workshop and then to White Columns. In 1971, Gordon Matta-Clark, Carol Goodden, Tina Girouard, and Suzanne Harris opened the legendary “FOOD” restaurant run by artists in SoHo. Artists Space began in 1972 as a pilot project for the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA). Franklin Furnace was founded in 1974 by Martha Wilson. In 1974, the very emerging Cindy Sherman, Diane Bertolo, Charles Clough, Nancy Dwyer, Robert Longo, and Michael Zwack founded the alternative space Hallwalls in Buffalo, because they needed a place to show their artwork.

[9] Liam Gillick, Fiona Rae, Steve Park and Sarah Lucas, Ian Davenport, Michael Landy, Gary Hume, Anya Gallaccio, Henry Bond, Lala Meredith-Vula, Angela Bulloch, Damien Hirst, Angus Fairhurst, Mat Collishaw, Simon Patterson, Abigail Lane, Gillian Wearing, and Sam Taylor-Wood all graduated from Goldsmiths between 1987-1990.